По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

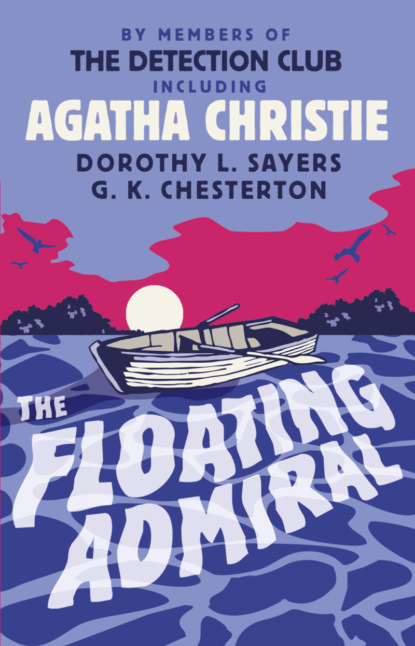

The Floating Admiral

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Some of the other contributors’ names have dropped off the radar almost completely—except in the consciousness of dedicated collectors—but I was interested to know a little about them, to help me visualise the composition of the Detection Club in its early years. So here are my findings:

Canon Victor L. Whitechurch was, as his title suggests, a clergyman, whose fictional creation Thorpe Hazell was a vegetarian railway detective, intended to be as different as possible from Sherlock Holmes. Whitechurch was one of the first crime writers to submit his manuscripts to Scotland Yard to check he’d got his police procedural details right (an effort that many contemporary practitioners of the genre still don’t bother to make).

G. D. H. (George Howard Douglas) and M. (Margaret) Cole were a husband and wife team of crime writers. Both left-wing intellectuals, in 1931 G. D. H. formed the Society for Socialist Inquiry and Propaganda, later to be renamed the Socialist League. Amongst the undergraduates he taught at Oxford was the future Prime Minister, Harold Wilson.

Henry Wade was the pseudonym of Henry Lancelot Aubrey-Fletcher, 6th Baronet, who was awarded both the D.S.O. and the Croix de Guerre for his bravery in the First World War. As well as writing twenty crime novels, he was High Sheriff of Buckinghamshire.

John Rhode was one of the pseudonyms of Cecil John Charles Street. Also writing as Miles Burton and Cecil Waye, in his lifetime he published over 140 books.

Milward Kennedy was the pseudonym of Milward Rodon Kennedy Burge, an Oxford-educated career civil servant, who specialised in police procedurals. He also wrote books under the androgynous name Evelyn Elder.

Edgar Jepson had an enormously varied literary career. As well as crime novels and popular romances, he wrote children’s stories and is probably best remembered now for his fantasy fiction. His son and daughter were both published authors and his granddaughter is the writer Fay Weldon.

So just a few snapshots of the 1931 Detection Club members who collaborated on The Floating Admiral. I find it intriguing to imagine the dinners they must have shared when they cooked up the ideas for this relay novel. Also the conversations … I’m sure, like contemporary members of the Detection Club, though they talked a bit about the craft of crime writing, it was when they got on to other topics that they became more energised. I can visualise religious discussions between the Catholic convert Ronald Knox, the Anglican canon Victor Whiteside and the Christian humanist Dorothy L. Sayers. I wonder how the idealistic Socialism of G. D. H. and M. Cole went down with the aristocratic Henry Wade. And, writing all those books, John Rhode must have had difficulty finding time to attend the dinners.

But enough nostalgia. One thing I am sure of, though … The dinners of the embryonic organisation, during which the plot of The Floating Admiral was hatched, would have been conducted in just the same spirit of good humour and congeniality which, I am glad to say, still characterises to-day’s Detection Club.

What can be wrong, after all, with an exclusive organisation of some sixty members which exists, in the words of Dorothy L. Sayers, “chiefly for the purpose of eating dinners together at suitable intervals and of talking illimitable shop”?

INTRODUCTION

By Dorothy L. Sayers

THE FLOATING ADMIRAL

WHEN members of the official police force are invited to express an opinion about the great detectives of fiction, they usually say with a kindly smile: “Well, of course, it’s not the same for them as it is for us. The author knows beforehand who did the job, and the great detective has only to pick up the clues that are laid down for him. It’s wonderful,” they indulgently add, “the clever ideas these authors hit upon, but we don’t think they would work very well in real life.”

There is probably much truth in these observations, and they are, in any case, difficult to confute. If Mr. John Rhode, for example, could be induced to commit a real murder by one of the ingeniously simple methods he so easily invents in fiction, and if Mr. Freeman Wills Crofts, say, would undertake to pursue him, Bradshaw in hand, from Stranraer to Saint Juan-les-Pins, then, indeed, we might put the matter to the test. But writers of detective fiction are, as a rule, not bloodthirsty people. They avoid physical violence, for two reasons: first, because their murderous feelings are so efficiently blown-off in print as to have little energy left for boiling up in action, and secondly, because they are so accustomed to the idea that murders are made to be detected that they feel a wholesome reluctance to put their criminal theories into practice. While, as for doing real detecting, the fact is that few of them have the time for it, being engaged in earning their bread and butter like reasonable citizens, unblessed with the ample leisure of a Wimsey or a Father Brown.

But the next best thing to a genuine contest is a good game, and The Floating Admiral is the detection game as played out on paper by certain members of the Detection Club among themselves. And here it may be asked: What is the Detection Club?

It is a private association of writers of detective fiction in Great Britain, existing chiefly for the purpose of eating dinners together at suitable intervals and of talking illimitable shop. It owes no allegiance to any publisher, nor, though willing to turn an honest penny by offering the present venture to the public, is it primarily concerned with making money. It is not a committee of judges for recommending its own or other people’s books, and indeed has no object but to amuse itself. Its membership is confined to those who have written genuine detective stories (not adventure tales or “thrillers”) and election is secured by a vote of the club on recommendation by two or more members, and involves the undertaking of an oath.

While wild horses would not drag from me any revelation of the solemn ritual of the Detection Club, a word as to the nature of the oath is, perhaps, permissible. Put briefly, it amounts to this: that the author pledges himself to play the game with the public and with his fellow-authors. His detectives must detect by their wits, without the help of accident or coincidence; he must not invent impossible death-rays and poisons to produce solutions which no living person could expect; he must write as good English as he can. He must preserve inviolable secrecy concerning his fellow-members’ forthcoming plots and titles, and he must give any assistance in his power to members who need advice on technical points. If there is any serious aim behind the avowedly frivolous organisation of the Detection Club, it is to keep the detective story up to the highest standard that its nature permits, and to free it from the bad legacy of sensationalism, clap-trap and jargon with which it was unhappily burdened in the past.

Now, a word about the conditions under which The Floating Admiral was written. Here, the problem was made to approach as closely as possible to a problem of real detection. Except in the case of Mr. Chesterton’s picturesque Prologue, which was written last, each contributor tackled the mystery presented to him in the preceding chapters without having the slightest idea what solution or solutions the previous authors had in mind. Two rules only were imposed. Each writer must construct his instalment with a definite solution in view—that is, he must not introduce new complications merely “to make it more difficult.” He must be ready, if called upon, to explain his own clues coherently and plausibly; and to make sure that he was playing fair in this respect, each writer was bound to deliver, together with the manuscript of his own chapter, his own proposed solution of the mystery. These solutions are printed at the end of the book for the benefit of the curious reader.

Secondly, each writer was bound to deal faithfully with all the difficulties left for his consideration by his predecessors. If Elma’s attitude towards love and marriage appeared to fluctuate strangely, or if the boat was put into the boat-house wrong end first, those facts must form part of his solution. He must not dismiss them as caprice or accident, or present an explanation inconsistent with them. Naturally, as the clues became in process of time more numerous, the suggested solutions grew more complicated and precise, while the general outlines of the plot gradually hardened and fixed themselves. But it is entertaining and instructive to note the surprising number of different interpretations which may be devised to account for the simplest actions. Where one writer may have laid down a clue, thinking that it could point only in one obvious direction, succeeding writers have managed to make it point in a direction exactly opposite. And it is here, perhaps, that the game approximates most closely to real life. We judge one another by our outward actions, but in the motive underlying those actions our judgment may be widely at fault. Preoccupied by our own private interpretation of the matter, we can see only the one possible motive behind the action, so that our solution may be quite plausible, quite coherent, and quite wrong. And here, possibly, we detective-writers may have succeeded in wholesomely surprising and confounding ourselves and one another. We are only too much accustomed to let the great detective say airily: “Cannot you see, my dear Watson, that these facts admit of only one interpretation?” After our experience in the matter of The Floating Admiral, our great detectives may have to learn to express themselves more guardedly.

Whether the game thus played for our own amusement will succeed in amusing other people also is for the reader to judge. We can only assure him that the game was played honestly according to the rules, and with all the energy and enthusiasm which the players knew how to put into it. Speaking for myself, I may say that the helpless bewilderment into which I was plunged on receipt of Mr. Milward Kennedy’s little bunch of brain-teasers was, apparently, fully equalled by the hideous sensation of bafflement which overcame Father Ronald Knox when, having, as I fondly imagined, cleared up much that was obscure, I handed the problem on to him. That Mr. Anthony Berkeley should so cheerfully have confounded our politics and frustrated our knavish tricks in the final solution, I must attribute partly to his native ingenuity and partly to the energetic interference of the other three intervening solvers, who discovered so many facts and motives that we earlier gropers in the dark knew nothing about. But none of us, I think, will bear any malice against our fellow-authors, any more than against the vagaries of the River Whyn, which, powerfully guided by Mr. Henry Wade and Mr. John Rhode, twin luminaries of its tidal waters, bore so peacefully between its flowery banks the body of the Floating Admiral.

PROLOGUE

By G. K. Chesterton

“THE THREE PIPE DREAMS”

THREE glimpses through the rolling smoke of opium, three stories that still hover about a squalid opium joint in Hong Kong, might very well at this distance of time be dismissed as pipe dreams. Yet they really happened; they were stages in the great misfortune of a man’s life; although many who played their parts in the drama would have forgotten it by the morning. A large paper-lantern coarsely scrawled with a glaring crimson dragon hung over the black and almost subterranean entrance of the den; the moon was up and the little street was almost deserted.

We all talk of the mystery of Asia; and there is a sense in which we are all wrong. Asia has been hardened by the ages; it is old, so that its bones stick out; and in one sense there is less disguise and mystification about it than there is about the more living and moving problems of the West. The dope-peddlers and opium hags and harlots who made the dingy life of that place were fixed and recognised in their functions, in something almost like a social hierarchy; sometimes their vice was official and almost religious, as in the dancing-girls of the temples. But the English naval officer who strode at that instant past that door, and had occasion to pause there, was in reality much more of a mystery; for he was a mystery even to himself. There were bound up in his character, both national and individual, the most complex and contradictory things; codes and compromises about codes, and a conscience strangely fitful and illogical; sentimental instincts that recoiled from sentiment and religious feelings that had outlived religion; a patriotism that prided itself on being merely practical and professional; all the tangled traditions of a great Pagan and a great Christian past; the mystery of the West. It grew more and more mysterious, because he himself never thought about it.

Indeed there is only one part of it that anybody need think about for the purposes of this tale. Like every man of his type, he had a perfectly sincere hatred of individual oppression; which would not have saved him from taking part in impersonal or collective oppression, if the responsibility were spread to all his civilisation or his country or his class. He was the Captain of a battleship lying at that moment in the harbour of Hong Kong. He would have shelled Hong Kong to pieces and killed half the people in it, even if it had been in that shameful war by which Great Britain forced opium upon China. But when he happened to see one individual Chinese girl being dragged across the road by a greasy, yellow ruffian, and flung head-foremost into the opium-den, something sprang up quite spontaneously within him; an “age” that is never really past; and certain romances that were not really burned by the Barber; something that does still deserve the glorious insult of being called quixotic. With two or three battering blows he sent the Chinaman spinning across the road, where he collapsed in a distant gutter. But the girl had already been flung down the steps of the dark entry, and he precipitated himself after her with the purely instinctive impetuosity of a charging bull. There was very little in his mind at that moment except rage and a very vague intention of delivering the captive from so uninviting a dungeon. But even over such a simple mood a wave of unconscious warning seemed to pass; the blood-red dragon-lantern seemed to leer down at him; and he had some such blind sensation as might have overwhelmed St. George if, charging with a victorious lance, he had found himself swallowed by the dragon.

And yet the next scene revealed, in a rift of that visionary vapour, is not any such scene of doom or punishment as some sensationalists might legitimately expect. It will not be necessary to gratify the refined modern taste with scenes of torture; nor to avoid the vulgarity of a happy ending by killing the principal character in the first chapter. Nevertheless, the scene revealed was perhaps, in its ultimate effects, almost more tragic than a scene of death. The most tragic thing about it was that it was rather comic. The gleam of the tawdry lanterns in the dope-den revealed nothing but a huddle of drugged coolies, with faces like yellow stone, the sailors from a ship that had put into Hong Kong that morning, flying the Stars and Stripes; and the final feature of a tall English naval officer, wearing the uniform of the Captain of a British ship, behaving in a peculiar way and apparently under rather peculiar influences. It was believed by some that what he was performing was a horn-pipe, but that it was mingled with motions designed only to preserve equilibrium.

The crew looking on was American; that is to say, some of them were Swedish, several Polish, several more Slavs of nameless nationality, and a large number of brown Lascars from the ends of the earth. But they all saw something that they very much wanted to see and had never seen before. They saw an English gentleman unbend. He unbent with luxuriant slowness and then suddenly bent double again and slid to the floor with a bang. He was understood to say:

“Dam’ bad whisky but dam’ good. WhadImeansay is,” he explained with laborious logic, “whisky dam’ bad, but dam’ bad whisky dam’ good thing.”

“He’s had more than whisky,” said one of the Swedish sailors in Swedish American.

“He’s had everything there is to have, I should think,” replied a Pole with a refined accent.

And then a little swarthy Jew, who was born in Budapest but had lived in Whitechapel, struck up in piping tones a song he had heard there: “Every nice girl loves a sailor.” And in his song there was a sneer that was some day to be seen on the face of Trotsky, and to change the world.

The dawn gives us the third glimpse of the harbour of Hong Kong, where the battleship flying the Stars and Stripes lay with the other battleship flying the Union Jack; and on the latter ship there was turmoil and blank dismay. The First and Second Officers looked at each other with growing alertness and alarm, and one of them looked at a watch.

“Can you suggest anything, Mr. Lutterell?” said one of them, with a sharp voice but a very vague eye.

“I think we shall have to send somebody ashore to find out,” replied Mr. Lutterell.

At this point a third officer appeared hauling forward a heavy and reluctant seaman; who was supposed to have some information to give, but seemed to have some difficulty in giving it.

“Well, you see, sir, he’s been found,” he said at last. “The Captain’s been found.”

Something in his tone moved the First Officer to sudden horror.

“What do you mean by found?” he cried. “You talk as if he was dead!”

“Well, I don’t think he’s dead,” said the sailor with irritating slowness. “But he looked dead-like.”

“I’m afraid, sir,” said the Second Officer in a low voice, “that they’re just bringing him in. I hope they’ll be quick and keep it as quiet as they can.”

Under these circumstances did the First Officer look up and behold his respected Captain returning to his beloved ship. He was being carried like a sack by two dirty-looking coolies, and the officers hastily closed round him and carried him to his cabin. Then Mr. Lutterell turned sharply and sent for the ship’s doctor.

“Hold these men for the moment,” he said, pointing to the coolies; “we’ve got to know about this. Now then, Doctor, what’s the matter with him?”

The doctor was a hard-headed, hatchet-faced man, having the not very popular character of a candid friend; and on this occasion he was very candid indeed.

“I can see and smell for myself,” he said, “before I begin the examination. He’s had opium and whisky as well as Heaven knows what else. I should say he’s a bag of poisons.”

“Any wounds at all?” asked the frowning Lutterell.

“I should say he’s knocked himself out,” said the candid doctor. “Most likely knocked himself out of the Service.”

“You have no right to say that,” said the First Officer severely. “That is for the authorities.”

“Yes,” said the other doggedly. “Authorities of a Court Martial, I should say. No; there are no wounds.”