По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

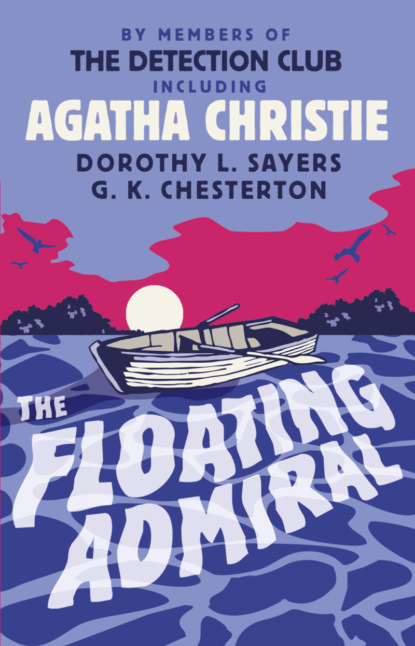

The Floating Admiral

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Thus do the first three stages of the story reach their conclusion; and it must be admitted with regret that so far there is no moral to the story.

CHAPTER I

By Canon Victor L. Whitechurch

CORPSE AHOY!

EVERYONE in Lingham knew old Neddy Ware, though he was not a native of the village, having only resided there for the last ten years; which, in the eyes of the older inhabitants who had spent the whole of their lives in that quiet spot, constituted him still a “stranger.”

Not that they really knew very much about him, for the old man was of a retiring disposition and had few cronies. What they did know was that he was a retired petty officer of the Royal Navy, subsisting on his pension, that he was whole-heartedly devoted to the Waltonian craft, spending most of his time fishing in the River Whyn, and that, though he was of a peaceful disposition generally, he had a vocabulary of awful and blood-curdling swearwords if anyone upset him by interfering with his sport.

If you, being a fellow-fisherman, took up your position on the bank of the River Whyn in a spot which Neddy Ware considered to be too near his, he would let drive at you with alarming emphasis; if boys—his pet aversion—annoyed him in any way by chattering around him, his language became totally unfit for juvenile ears. Once young Harry Ayres, the village champion where fisticuffs were concerned, had the temerity to throw a stone at the old man’s float; he slunk back home afterwards, white in face and utterly cowed with the torrent of Neddy Ware’s lurid remarks.

He lived in a small cottage standing quite by itself on the outskirts of the village, and he lived there alone. Mrs. Lambert, a widow, went to his cottage for a couple of hours every morning to tidy up and cook his midday meal. For the rest, Neddy Ware managed quite well.

He came out of his cottage one August morning as the church clock, some half a mile distant, was striking four. Those who knew his habits would have seen nothing unusual in his rising so early. The fisherman knows the value of those first morning hours; besides which, the little River Whyn, which was the scene of his favourite occupation, was tidal for some five or six miles from the sea. For those five or six miles it meandered, first through a low valley, flanked by the open downs on one side and by wooded heights on the other, and then made its way, for the last four miles, through a flat, low-lying country till it finally entered the Channel at Whynmouth. Everyone knows Whynmouth as a favourite South Coast holiday resort, possessing a small harbour at the mouth of its river.

Twice a day the tide flowed up the Whyn, more or less rapidly according to whether it was “spring” or “neap.” And this fact had an important bearing on the times which were favourable for angling. On this particular morning Neddy Ware had planned to be on the river bank a little while after the incoming tide had begun to flow up the stream.

Behold him, then, as he came out of his cottage, half-way up the wooded slopes of “Lingham Hangar,” crossed the high road, and made his way down to the level of the river. He was fairly on in years, but carried those years well, so much so that there was only just a sprinkling of grey in his coal-black hair. A sturdy-looking man, cleanshaven, but with a curious, old-fashioned twist of hair allowed to grow long on either side of his head just in front of his ears; brown, weatherbeaten, lined face, humorous mouth and keen, grey eyes. Dressed in an old navy blue serge suit, and wearing—as he invariably did—a black bowler hat. Carrying rods, landing net, and a capacious basket containing all kinds of the impedimenta of his craft.

He reached the grassy bank of the river, put his things on the ground, and very slowly filled a blackened clay pipe with twist tobacco—which he rubbed in his hands first—and proceeded to light it, glancing up and down the river as he did so.

Where he was standing the river took a curve, and he was on the outer side of this curve, on the right bank. Away to the left the stream bent itself between the heights on the one side and open meadows on the other. To the right, bending away from him, was the flat country, the river’s edges bordered with tall-growing reeds. From this direction the tide was flowing towards him, swirling round the bend.

His first task was to haul in three or four eel lines he had thrown out the evening before, the ends being tied to the gnarled roots of a small tree growing on the bank. Two of the lines brought to land a couple of fair-sized eels, and, very dexterously, he detached the slippery, twisting fish from the hooks, washing the slime off afterwards. Then, slowly, he commenced putting one of his rods together, arranging his tackle, baiting with worms, and casting into the stream. For some little time he watched the float bobbing about in the swirl of the eddies, now and again striking when it suddenly disappeared beneath the surface, once landing a fish.

He glanced around. Suddenly his float lost interest. He was gazing down-stream, as far as he could see around the bend. Slowly a small rowing-boat was coming up-stream. But there was something peculiar about her. No oars were in evidence. She appeared to be drifting.

The old sailor was quick to recognise the little craft.

“Ah,” he muttered, “that’s the Vicar’s boat.”

Lingham Vicarage stood, with its adjacent church, quite apart from the village proper, about half a mile down the river. The grounds ran down to the water’s edge, where there was a rough landing-stage. The Vicar, he knew, kept his boat at this stage, moored by her painter to a convenient post. There was a little creek running into the grounds, with a wooden boat-house, but, in the summer months, especially when the Vicar’s two boys were home from school, the boat was generally kept on the river itself.

As it came nearer, Ware laid down his rod. He could see now that there was someone in the boat—not seated, but, apparently, lying in the bottom of her, astern.

The boat was only about fifty yards away now. The swirl of the tide was bringing her round the outer side of the bend in the river, but Neddy Ware, who knew every current, saw that she would pass beyond his reach. With the quick action of the sailor he did not waste an instant. Diving into his basket he produced one of the coiled up eel lines with its heavy, lead plummet. And then stood in readiness, uncoiling the line and throwing the slack on the grass.

On came the boat, about a dozen yards from the bank. Skilfully he threw the plummet into her bows, and then started walking along the bank up-stream, gently but steadily pulling on the line till, at length, he brought her close up to the bank and laid hold of the painter at her bows. The end of the painter was dragging in the water. As he pulled it out he glanced at it. It had been cut.

He made it fast to a tree-root. The boat swung round, stern up-stream, alongside the bank. And Ware got into her. The next moment he was on his knees, bending over the man who lay in the stern.

He lay there on his back, his knees slightly hunched up, his arms at his sides, quite still. A man of about sixty, with iron-grey hair, moustache and close-cropped, pointed beard, dark eyes open with fixed stare. He was clad in evening dress clothes and a brown overcoat, the latter open at the front and exposing a white shirt-front stained with blood.

Sitting on one of the seats, Ware made a swift examination of the boat.

A pair of oars lay in her, the metal rowlocks were unshipped. Apparently the dead man was hatless—no—there was a hat in the boat, lying in the bows; a round, black, clerical hat, such as Mr. Mount, the Vicar, usually wore.

Neddy Ware, having looked around, got out of the boat and glanced at his watch. Ten minutes to five. Then, leaving the little craft moored to the bank, he hurried off as fast as he could go, gained the high road, which was some hundred yards away from the river, and started in the direction of the village.

Police Constable Hempstead, just on the point of turning into bed after having been on duty all night, looked out of the window in answer to Ware’s knock at the door.

“What is it, Mr. Ware?” he asked.

“Something pretty bad, I’m afraid.”

Hempstead, wide awake now, slipped on his clothes again, came down and opened the door. Ware told him what had happened.

“I must get the Inspector out from Whynmouth—and a doctor,” said the constable, “I’ll phone to the station there.”

He came out again in two or three minutes.

“All right,” he said. “They’ll run over in a car at once. Now you come along with me and show me that boat and what’s in it. You haven’t been messing about with anything—moving the body and so on, I hope?”

“I shouldn’t be such a fool,” replied Ware.

“That’s all right. You haven’t seen anyone else?”

“No one.”

The policeman went on asking questions from time to time as they hurried along. He was a smart man, this young constable, eager for his stripes, and wanted to make the most of the opportunity. As soon as they reached the river bank he took a glance at the boat and its contents, and exclaimed:

“Hullo! Don’t you know who that is, Mr. Ware?”

“Never saw him before that I know of. Who is he?”

“Why, it’s Admiral Penistone. He lives at Rundel Croft—that big house the other side of the river just opposite the Vicarage. Leastways, he’s been in residence there about a month. He only bought it last June. A new-comer.”

“Oh! Admiral Penistone, is he?” said Neddy Ware.

“That’s the man, right enough. But, look here: are you sure this is the Vicarage boat?”

“Certain.”

“Queer, eh? That seems to mean something happened this side of the river, for of course there’s no bridge till you get to Fernton—three miles lower down. Ah, and the parson’s hat, eh? Let’s see; what time did you first see the boat coming along?”

“A little after half-past four, I should say.”

Hempstead had his note-book out and was making pencilled jottings in it. Then he said:

“Look here, Mr. Ware, I want you, if you will, to go back to the road and stop Inspector Rudge when he comes along in his car.”

“Very well,” replied Ware; “nothing more I can do?”

“Not yet, at any rate.”

Hempstead was an astute man. He waited until Neddy Ware was out of the way before he began a little examination on his own account. He knew very well that his superior officer would take the case fully in hand, but he was anxious to see what he could, without disturbing anything, in the meantime.