По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

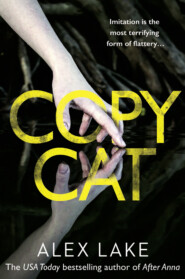

After Anna

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

You’re just having a bloody midlife crisis, Brian said. I thought it was me that was supposed to get scared about life leaking away and spend our savings on a sports car and have an affair with a bimbo.

And then she said the thing she really regretted.

I wish you would, she’d said. At least I could find something interesting in a man who had some fight in him. You’re ready for the pipe and slippers phase already.

What, he said, suddenly red-faced. What did you say?

She repeated herself. That you’re ready for your pipe and slippers. Julia found it odd that this, of all she’d said, was the thing that he was particularly exercised by, but his reply enlightened her.

Not that, he said. Not the bloody pipe and slippers.You said you could find something interesting in a man with some fight in him. So I’m not even interesting to you?

Julia realized that she hadn’t been making that statement – it had just kind of slipped out – but now it was said it was exactly what she meant. So she nodded.

You can think I’m boring, Brian replied, and lacking inspiration, or whatever it is you’ve read on Facebook that you should be looking for, I can accept that. What I can’t accept is you saying that there’s nothing about me that deserves your interest. Not your respect, and not, heaven forbid, your love, but your interest. If that’s the case it really is over.

And she had agreed. She told him he had put it well. That he really understood the situation.

Since then they had barely spoken. Brian slept in the guest room; she stayed in their room. On the few occasions they had been unable to avoid sharing words they had not discussed their future, until about ten days ago, when she had told him she’d made up her mind. She wanted a divorce.

Which was what Carol Prowse wanted, and would get. The problem was that she also wanted her husband only to have custody of their nine-year-old son when supervised. Her demand was ridiculous and vindictive, and it would never be granted.

Jordi Prowse had shaken his head when Julia said it, and now he was laughing.

‘Forget it,’ he said. His hair was greying at the temples and he had a relaxed, easy manner. ‘That’s simply unthinkable. There’s no grounds for that.’

There was a long pause. Carol Prowse looked at Julia. ‘That’s not what my lawyer thinks.’

That was what her lawyer thought, but it was not what Councillor Prowse wanted her to say. Julia glanced again at the time. Two fifty. She needed to wrap this up.

‘Given the age of the girls you were having an affair with I think that there are grounds to argue that you are not fit to be left in charge of a child,’ she said. ‘Moral grounds.’

His lawyer, an old friend of Julia’s called Marcie Lyon, shook her head. ‘There’s no way that’ll fly,’ she said. ‘You know that.’

Jordi grinned. ‘You’re just feeling humiliated,’ he said. ‘So you’re making empty threats.’

Carol Prowse stiffened in her chair. Julia had been here before, this could get ugly. It was the way that custody battles went. Both parties went in with the best intentions to reach an amicable settlement; both parties ended up locked in a battle for their kids, which ripped whatever was left of their relationship to pieces. But she couldn’t wait around to see this one. She looked at the clock again. ‘I think,’ she said, ‘that we might have achieved all we are going to achieve today. I would suggest that Ms Lyon and I meet later in the week to discuss the case.’

Jordi West shrugged. ‘Sure,’ he said. ‘You can meet and discuss how stupid her—’, he nodded at his wife ‘proposal is.’

Julia smiled. ‘We’ll discuss many things, I’m sure,’ she said. ‘Can we consider this meeting over?’

She had to get out of the room. She had accepted that she was not going to make it in time to pick up the puppy – it was a twenty-five-minute drive to the school, then another half hour to the lady’s house – but now she had a more pressing concern. She needed to call the school and tell them she was running late so they could hold Anna back. She got to her feet, aware that she was rushing the three other people in the room. Marcie gave her an odd look as she left; Jordi didn’t look at either Julia or her client.

Carol Prowse shook her head. ‘Can you believe that?’ she said. ‘He’s so damn arrogant.’

Julia could see that her client was in the mood to debrief, and normally she would have provided the sympathetic support she wanted, but right now that was simply not an option. She nodded agreement. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘I have to go. It’s my day to pick up my daughter from school.’

God, it sounded lame. This was the problem. She was expected to be a model professional, focused on her career, which meant she was at the beck and call of her clients, as well as being a model parent, which meant she was at the beck and call of her daughter. It was impossible to be both, but that didn’t lessen the expectation any.

In the corridor she took her phone from her bag and pressed the button.

The screen was black. It was out of battery.

She swore quietly. She fished around in her bag for a charger. Not there; of course not. It was in the car. She could run up to her office and call from there, but it was on the other side of the building. No – the quickest way was to get to the car and charge it there.

She hurried down the corridor. She didn’t doubt everything would be fine, but she still didn’t like the feeling of being late to pick up her daughter.

ii.

As she drove away from the office, Julia tapped her finger on the logo at the centre of the screen of her phone, even though she knew it would not shorten whatever process it went through when it switched on. She did the same thing when waiting for a lift; if it was slower to arrive than expected she would press the call button again. And sometimes again.

Won’t come any faster, some wag might say, and she’d reply, with a thin smile, well,you never know.

Come on, she thought. Come on.

This had happened before, resulting in an uncomfortable encounter with Mrs Jameson, the retired teacher who stayed after school with the children whose parents had neglected to turn up on time. It was going to happen again today. There’d be the stern, disappointed look, then the gentle reminder of school policy.

Mrs Crowne, I realize you are busy but could I remind you that the school cannot provide after-hours childcare without prior arrangements being made. If you need such assistance then we can provide it, but you must inform us ahead of time so that we can make the necessary arrangements.

I’m sorry, she’d mumble, feeling like she was back at school herself, hauled in front of the head teacher for smoking or wearing her skirt an inch too short, but my case ran over and I would have called but my phone ran out of juice and thank you Mrs Jameson for being so flexible. I appreciate it, I really do.

And then she’d leave, feeling like a terrible parent but wondering why, since Anna would be perfectly fine, babbling away in the back seat, telling Julia about her day and asking what was for dinner and could they read The Twits again that night, and Julia would be shaking her head and thinking I’m not a bad mother, just a busy one.

And she was about to get busier. When she and Brian separated she would have to pick up almost every day, and God knew how she was going to do that. At least now she had Edna, Brian’s mum, to help: she took Anna on Mondays and Wednesdays, and Brian normally got out of school early enough to get her on Fridays, which left Julia with two days on which she had to cram her meetings into the morning and spend the evenings catching up on emails. From time to time, if she was going to be late, she could give Edna a call; in fact she had tried that morning, but Edna was out so she had left a message, a message that Edna had ignored. And then, damn it, in the dash from one meeting to another she had stupidly let her phone run out of battery. Mental note: always keep the phone charged on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

And maybe other days as well. She doubted she would be able to rely on Edna after the divorce; behind her sweetness, Edna was a traditional matriarch, and Julia had never felt that she liked her son’s wife all that much.

Anyway, it would be what it would be. Whatever happened, Julia could take it. That was the price she would have to pay for the life she wanted.

Finally, her phone beeped as it booted up. She found the school’s number and pressed send. It rang through to the answering service pick up.

‘This is Julia Crowne,’ she said. ‘I’m running a little late, but I should be there—’, she glanced at the clock on the dashboard ‘around three twenty. Anyway, just to let you know, I’m coming.’

Ten minutes later she arrived at the school. As she pulled up outside the school gates, her phone rang. She unplugged it from the car and opened the door.

‘Hello,’ she said. ‘This is Julia.’

‘Mrs Crowne,’ a voice said. ‘This is Karen, from Westwood School.’

‘Oh,’ Julia said. ‘Don’t worry. I’m here. I just arrived.’

‘Mrs Crowne,’ Karen said, her voice uncertain, ‘do you have Anna with you?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘I’m coming to pick her up. I left a message.’

‘I thought that was what you said,’ Karen murmured. ‘Mrs Crowne, I think there’s been a mix-up.’

A mix-up. Not words you wanted to hear in connection with your five-year-old daughter.