По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

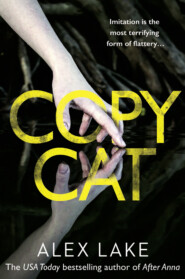

After Anna

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I see. Well, it’s a busy job. So when you got here, there was no sign of Anna?’

Julia explained what she had done, how she had guessed that Anna would be in The Village Sweete Shoppe and gone down there, how she had asked some people for help, how she had searched the village until Brian called. When she was finished, DI Wynne nodded and chewed her lip thoughtfully.

She turned to the headmistress. ‘Mrs Jacobsen, I’ll need a list of all the parents and children who were at the school today, as well as all the employees of the school, whether they were here or not.’

Mrs Jacobsen nodded. ‘It’s not only parents who pick up the pupils,’ she said. ‘But we have a register of all those who are permitted to do so. I can let you have it.’

‘Do you have CCTV inside the school?’

Mrs Jacobsen’s mouth tightened into a slight moue. ‘Yes,’ she said. ‘We do. Much as I prefer the promotion of civil liberties – we aim to produce responsible citizens who do the right thing because it is the right thing to do, and not because they think they are being observed – we have bent to the general panic about these matters and have installed CCTV.’

‘You must be glad you did, now,’ DI Wynne said. ‘And there might be something else in the area we can use. Could you make sure that the officers get access to the CCTV?’

‘Of course,’ Mrs Jacobsen said. ‘Right away.’

‘I have a question,’ Brian said, turning to the headmistress, his face a dark red. ‘How the hell did this happen? I thought the teachers did not let children out of the grounds unless they knew there was a parent there?’

That was right, Julia thought. The school had a pick-up policy and it was strictly adhered to. Only parents or designated carers could pick up children, although they were not allowed on the school grounds; the pupils were accompanied to the school gates and handed over to their responsible adults. In the case of an adult being late, they were to notify the school, and that pupil stayed inside. If, as Julia had done, the adult failed to notify the school, then the child would be ok: they would be left at the gates with a teacher, and brought inside to wait.

But it hadn’t worked this time.

‘I’ve spoken to the teachers,’ Mrs Jacobsen said. ‘They said that they thought you were there, Mrs Crowne. They expected you to be there since you had not called to say you would not be.’

‘She wasn’t there, though, was she!’ Brian said. ‘And you were supposed to take care of my daughter! That’s what we pay your obscene school fees for!’

‘Mr Crowne,’ the headmistress said. ‘The school adhered to its policies. I am sure the CCTV will show that. We do everything we can to ensure the safety—’

‘But not enough!’ Brian shouted.

‘We have policies in place that have been independently reviewed and which are in accordance with all necessary legislation,’ Mrs Jacobsen said. ‘And I am, of course, open to any questions you and Julia might have, but I’m not sure that now is the best time to discuss them.’

‘Fine,’ Julia said. ‘We can discuss it later.’ She glanced at DI Wynne. ‘For now we need to concentrate on finding Anna.’

‘Precisely,’ DI Wynne said. ‘If you could get me the CCTV and the personnel list, that would be a start.’ She turned to Julia and Brian. ‘I’d like a recent photo of Anna, as well. So that we can alert other constabularies and the border control folks.’

‘You think that’s necessary?’ Brian asked. ‘You think she might be being taken out of the country?’

‘I wouldn’t jump to conclusions,’ DI Wynne said. ‘But it’s a precaution worth taking.’

‘God,’ Brian said. He covered his eyes with his hand. ‘This can’t be happening. It just can’t. Not again. I can’t believe it’s happening again.’

vi.

Detective Inspector Wynne stared at Brian.

‘Again?’ she said. Her calm expression was suddenly more urgent. ‘You’ve had a child disappear before?’

Brian shook his head. ‘No,’ he said. ‘Not a child. My father. He left home when I was in my early twenties. He vanished. Didn’t leave a note; nothing. Just went.’

‘Have you heard from him since?’ DI Wynne asked.

‘No.’ Brian looked at his hands. He picked at the cuticle of his left index finger. ‘Not a word. Not even a Christmas card.’

‘And you don’t know where he is? He just disappeared?’ DI Wynne pressed.

‘Yep.’ Brian shrugged. ‘It was during the school holidays. Dad was a headmaster. He was nearing retirement. One day he was there, and the next he wasn’t.’

‘And you don’t know why? Or where he went?’

‘No. No idea.’

Julia knew that Brian was not quite telling the truth. Yes, he had no idea where his father was, but he did have some idea of why he had gone there. He had told her once – and made her swear that she would not ever tell Edna that he had discussed it with her – that he suspected his headmaster father had been having an affair with a younger member of staff and had run away with her. He wasn’t sure – his mother never talked about it – but he had managed to piece that much together over the years.

Still, he had no idea where his dad had gone, nor why he had never got in touch with him.

Julia had an idea. Not of where he was, but of why he hadn’t been in touch. She suspected it was the price he paid for his freedom: Jim had an affair and Edna gave him an ultimatum: get out of her life and start again with his girlfriend somewhere far from her, and she’d let him go quietly. Let him avoid the disgrace. The catch was that he had to stay away, from both her and Brian.

Or he could stick around and she’d make his life a misery. And Edna would be good at that.

So off he’d gone, probably to some beach in Spain or chalet in Switzerland, where he spent his days hiking and reading and skiing while his young bride taught in an international school and had discreet affairs of her own.

Maybe, anyway. Julia didn’t know for sure. All she knew was that it had hit Brian hard, and now, from his point of view, it was happening again.

‘We’ll want to get in touch with him,’ DI Wynne said. ‘Any information you have would be most helpful.’

‘I don’t have any,’ Brian said. ‘I can ask mum.’

‘Thank you,’ DI Wynne said. ‘I appreciate it.’

She wouldn’t get much from Edna, Julia thought, but she could try.

‘Right,’ Brian said. ‘And that’s enough standing around. I’m going to look for my daughter.’

Julia watched him leave. She looked at DI Wynne.

‘I’m going too,’ she said.

DI Wynne nodded. ‘Of course. I’ll be here.’ She wrote down her phone number. ‘Call if you find her.’

As she picked up her car keys, her phone rang.

It was Edna. She lifted the phone to her ear. Before she could speak, she heard Edna’s strident tones.

‘Julia, what’s going on? Brian left me a message, about Anna. I tried to call him but he didn’t answer.’

Julia swallowed, hard.

‘She’s missing,’ she said. ‘She’s gone missing.’