По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

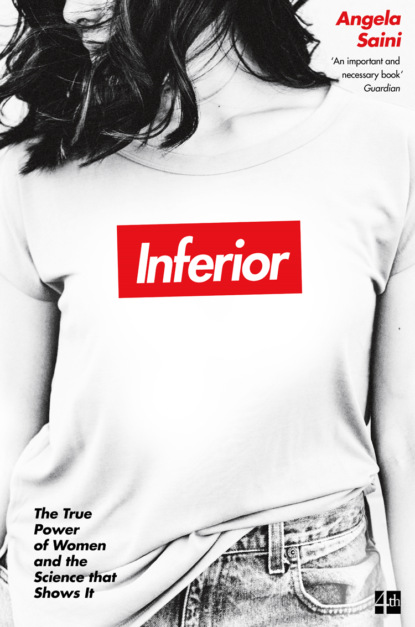

Inferior: How Science Got Women Wrong – and the New Research That’s Rewriting The Story

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It’s an issue that runs through other corners of science too. In research on the evolution of genitals (parts of the body we know for certain are different between the sexes), scientists have also leaned towards males. In 2014 biologists at Humboldt University in Berlin and Macquarie University in Sydney analysed more than three hundred papers published between 1989 and 2013 that covered the evolution of genitalia. They found that almost half looked only at the males of the species, while just 8 per cent looked only at females. One reporter, Elizabeth Gibney, described it as ‘the case of the missing vaginas’.

When it comes to health research, the issue is more complicated than simple bias. Until around 1990, it was common for medical trials to be carried out almost exclusively on men. There were some good reasons for this. ‘You don’t want to give the experimental drug to a pregnant woman, and you don’t want to give the experimental drug to a woman who doesn’t know she’s pregnant but actually is,’ says Arthur Arnold. The terrible legacy of women being given thalidomide for morning sickness in the 1950s proved to scientists how careful they need to be before giving drugs to expectant mothers. Thousands of children were born with disabilities before thalidomide was taken off the market.

‘You take women of reproductive age off the table for the experiment, which takes out a huge chunk of them,’ continues Arnold. A woman’s fluctuating hormone levels might also affect how she responds to a drug. Men’s hormone levels are more consistent. ‘It’s much cheaper to study one sex. So if you’re going to choose one sex, most people avoid females because they have these messy hormones … So people migrate to the study of males. In some disciplines it really is an embarrassing male bias.’

This tendency to focus on males, researchers now realise, may have harmed women’s health. ‘Although there were some reasons to avoid doing experiments on women, it had the unwanted effect of producing much more information about how to treat men than women,’ Arnold explains. A 2010 book on the progress in tackling women’s health problems, co-written by the Committee on Women’s Health Research, which advises the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the USA, notes that autoimmune diseases – which affect far more women than men – remain less well understood than some other conditions: ‘Despite their prevalence and morbidity, little progress has been made toward a better understanding of those conditions, identifying risk factors, or developing a cure.’

Another problem is that women may respond differently from men to certain drugs. Medical researchers in the mid-twentieth century often assumed this wasn’t a problem. ‘There was a notion that women were more like little men. There was a notion that if this treatment works in men, it will work on women,’ says Janine Clayton, director of the Office of Research on Women’s Health at the NIH in Washington, DC, which funds the vast majority of American health research.

We now know this isn’t necessarily true. In 2001, New Zealand-based dermatologist Marius Rademaker estimated that women are around one and a half times as likely to develop an adverse reaction to a drug as men. In 2000 the United States Government Accountability Office looked at the ten prescription drugs withdrawn from the market since 1997 by the US Food and Drug Administration. Studying reported cases of adverse effects, it found that eight posed greater health risks to women than to men. The withdrawn drugs included two appetite suppressants, two antihistamines and one for diabetes. Four of these were simply given to many more women than men, but the other four showed this effect even when men took them in more equal numbers.

‘You have to be concerned that there were serious enough side effects, not just a minor side effect but a serious enough adverse effect that resulted in the drug being withdrawn. I think that tells us that we’re only just seeing the tip of the iceberg of this issue,’ Janine Clayton tells me. This has become a huge concern for women’s health activists, particularly in the United States, and has been one of the mandates of the Office of Research on Women’s Health since 1990.

‘As clinicians, we know very well that diseases show up differently in men and women. Every day, men and women present to the emergency room with different symptoms with the same condition,’ says Clayton. ‘So heart attacks, for example, have different symptoms. Our research has shown that women who are going to have a myocardial infarction [heart attack] are more likely to have symptoms like insomnia, increasing fatigue, pain anywhere in the head all the way down to the chest, the weeks before they have a heart attack. Whereas men are less likely to have those symptoms, and are more likely to present with the classic crushing chest pain.’ Given differences like these, she believes that excluding them from drug trials for so many years must have affected women’s health. ‘It’s certainly a real possibility that the reason there are more adverse events in women than in men is because the whole process of drug discovery is tremendously biased towards the male,’ agrees Kathryn Sandberg.

Again, though, this line of thinking risks drawing divisions between women and men, when the picture of disease is far more complicated. While there’s a clear benefit to better understanding women’s bodies and having drugs that suit both sexes, the emphasis on sex difference starts to make it seem as though women’s bodies are from Venus and men’s are from Mars. ‘Given the well-documented history of methodological problems with sex difference research, as well as harmful abuses of sex difference claims by those who would limit women’s opportunities, it is remarkable to find women’s health activists promoting, with little qualification, sex-based biology’s expansive picture of sex differences,’ writes Sarah Richardson in Sex Itself.

But does it have to be one or the other? Is the only alternative to women being thought of as ‘little men’ to have them treated as an entirely different kind of patient? As more detailed research is done, it’s becoming clear that seeing some variation between women and men when it comes to health and survival doesn’t mean we should ditch the notion that our bodies are in fact similar in most ways.

This is a cautionary tale of two drugs.

The first is digoxin, which has long been used to treat heart failure. In 2002 researchers at the Yale University School of Medicine decided to take a look at the data around the drug, analysing its effects by sex. Between 1991 and 1996, other researchers had carried out randomised trials on heart patients using digoxin. They found that it didn’t affect how long a patient lived, but it did on average reduce their risk of hospitalisation. The Yale researchers noted that the drug was tested on around four times as many men as women, and that they didn’t respond identically. A slightly higher proportion of women taking digoxin died earlier than those taking a placebo. For men, the gaps between those taking the drug and the placebo group were much smaller. The sex difference, the Yale team concluded, ‘would have been subsumed by the effect of digoxin therapy among men’.

But science never stands still. The Yale result later turned out not to be what it seemed. More recent studies, including one with a much larger sample group published in the British Medical Journal in 2012, have suggested that in fact there isn’t a substantially increased risk of death for women from digoxin use at all.

The second example is the insomnia drug zolpidem, commonly sold in the United States under the brand name Ambien. Sleeplessness is big business for pharmaceutical companies. Around sixty million sleeping pills were prescribed in the US in 2011, up from forty-seven million just five years earlier, according to data collected by the healthcare intelligence company IMS Health. And Ambien is among the most popular. Its side effects, however, include severe allergic reactions, memory loss and the possibility of it becoming habit-forming. The effects of zolpidem can also lead to drowsiness the following day, which can make it dangerous to drive. Long after the drug was approved for market, research emerged that women given the same dose as men were more likely to suffer this morning drowsiness. Eight hours after taking zolpidem, 15 per cent of women but only 3 per cent of men had enough of the drug in their system to increase their risk of a traffic accident.

At the start of 2013 the US Food and Drug Administration took the landmark decision to lower the recommended starting dose of Ambien, halving it for women. ‘Zolpidem is kind of like a signal case,’ says Arthur Arnold.

Again though, just as with digoxin, the finding needed to be unpicked a little further. In 2014, additional research exploring the effects of zolpidem, carried out by scientists at Tufts University School of Medicine in Boston, suggested that its lingering effect in women may be mostly down to the fact that they have a lower average body weight than men, which means the drug clears from their systems more slowly.

Digoxin and zolpidem highlight the pitfalls of including sex as a variable in medical research. Besides a lower average body weight and height, women also have a higher percentage of body fat than men on average. And they generally take longer to pass food through their bowels. Both are things that might affect how drugs behave in their bodies. But they are also factors on which men and women overlap. There are many women who are heavier than the average man, for instance. It’s not always the case that the sexes belong in two separate categories.

What also counts is the experience of being a woman, socially, culturally and environmentally. ‘Both sex and gender are important factors for health,’ says Janine Clayton. Ideally, then, people should be treated according to the spectrum of factors that set them apart. Not just sex, but social difference, culture, income, age and other considerations. As Sarah Richardson has written, ‘a female rat – not to mention a cell line – is not an embodied woman living in a richly textured social world’.

The problem is that ‘medicine is very binary. Either you get the drug or you don’t. Either you do this or you do that,’ says Sabine Oertelt-Prigione. ‘So the only step, I believe, is to incorporate the notion that there is actually not one neutral body, but at least two. I believe it’s just another way of looking at things. In medicine, just having a way to change paradigms and look at things differently can open up whole arrays of possibilities. It could be looking at sex differences, but there are many other things that could help to make healthcare more inclusive in the end.’

‘What are we trying to do? We’re trying to improve human health, right?’ says Kathryn Sandberg. ‘So if we see a disease is more prevalent or more aggressive in men than women, or vice versa, we can learn a lot about that disease by studying why one sex is more susceptible while the other is more resilient. And this information can lead to new treatments that benefit all of us.’ Understanding why women tend to live longer could help men live longer. Including pregnant women in research may open up the cabinet of drugs that doctors can’t currently prescribe because their effects on foetuses are uncertain. Medical dosages might be affected by a better understanding of how a woman’s body responds across her menstrual cycle.

At the moment at least, the verdict of politicians and scientists seems to be that including sex as a variable when carrying out medical research can improve overall health. In 1993 the US Congress introduced the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act, which includes a general requirement for all NIH-funded clinical studies to include women as test subjects, unless they have a good reason not to. By 2014, according to a report in Nature by Janine Clayton, just over half of clinical-research participants funded by the NIH were women.

Since the start of 2016 the law in the USA has been broadened to include females in vertebrate animal and tissue experiments. The European Union now also requires the researchers it funds to consider gender as part of their work.

For women’s health campaigners and researchers like Janine Clayton and Sabine Oertelt-Prigione, this is a victory. To have females equally represented in research is something they’ve spent decades fighting for. Male bias, where it exists, is being swept away. Women are being taken into account. Maybe we will finally understand just what it is that makes women on average better survivors, and why men seem to report less sickness.

But as science enters this new era, scientists need to be careful. Research into sex differences has an ugly and dangerous history. As the examples of digoxin and zolpidem prove, it’s still prone to errors and over-speculation. While it can improve understanding, it also has the potential to damage the way we see women, and to drive the sexes further apart. The work being done into genetic sex differences by people like Arthur Arnold doesn’t just impact medicine, but also how we see ourselves.

Once we start to assume that women have fundamentally different bodies from men, this quickly raises the question of how far the gaps stretch. Do sex chromosomes affect not just our health, but all aspects of our bodies and minds, for example? If every cell is affected by sex, does that include brain cells? Do oestrogen and progesterone not just prepare a women for pregnancy and boost her immunity, but also creep into her skull, affecting how she thinks and behaves? And does this mean that gender stereotypes, such as baby girls preferring dolls and the colour pink, are in fact rooted in biology?

Before we know it we land on one of the most controversial questions in science: are we born not just physically different, but thinking differently too?

3

A Difference at Birth (#ulink_1d80a452-0d4c-5c8a-bec1-473772408db0)

Girls and boys, in short, would play harmlessly together, if the distinction of sex was not inculcated long before nature makes any difference.

Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)

‘We live in jeans, don’t we? They go with everything!’ coos the mother. Her six-month-old daughter is wearing the tiniest pair of jeans I’ve ever seen, and she herself is dressed head to foot in denim.

We’re sitting together in the baby lab at Birkbeck College in central London. It reminds me of a nursery, but a somewhat unusual one. A purple elephant decorates the door to a waiting area full of toys. Downstairs, however, a baby might be hooked up to an electroencephalograph that monitors her brain’s electrical activity while she watches pictures on a screen. In another room, scientists could be watching a toddler play, examining which toys he happens to choose. Meanwhile, in this small laboratory that I’ve been invited into, a baby is being gently stroked along her back with a paintbrush. She’s the thirtieth infant to be studied so far in this experiment.

‘She really just likes sitting and watching, taking it all in. I’m happy sitting and observing, myself,’ her mother says, bouncing the little girl on her knee. Researchers suspect that human touch like this has an important impact on development in the early years. They just don’t know how or why. So the goal of today’s experiment is to measure how touch affects a baby’s cognitive development. It’s one of countless ways in which children are affected by their upbringing, slowly shaped into the people they will become.

Cute though babies are, studying them this way is not as much fun as it might seem. It’s almost like working with animals. The challenge is to come up with clever experiments that get to the heart of their behaviour without accidentally reading too much into what they do. A stare can be meaningful or mindless, while even the most charming smile may just be wind. In this particular case, the researchers are using a paintbrush in their touch experiment because that’s the only way to control for the fact that parents stroke their children in different ways. With a brush, they can be sure it’s the same every time.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: