По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

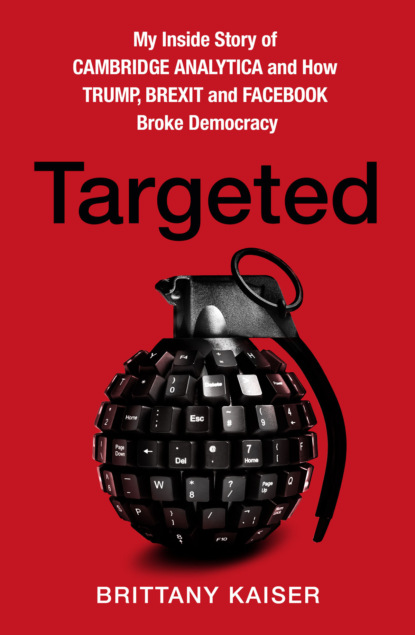

Targeted: My Inside Story of Cambridge Analytica and How Trump, Brexit and Facebook Broke Democracy

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

My change of identity wasn’t just online. In London, I opened up a big box my mother had sent me via FedEx; because she worked for the airlines, she had virtually free international shipping privileges. She had sent me business suit after business suit from her old closet: beautiful Chanel pieces, items by St. John, and specialty outfits from Bergdorf Goodman—what she’d worn years before, when she worked for Enron. I pictured what she looked like back then, when she left for work in the mornings back in Houston. She was always impeccably put together, dashing out the door in the highest of heels and those expensive suits, her makeup perfect. Now the suits were my hand-me-downs. I hung them in the closet of the new flat I’d rented for myself in Mayfair.

The flat was tiny, just one room with a kitchen counter and an electric burner and a bathroom far down a hall, but I’d chosen the place strategically. It was close to work and, more important, in the right neighborhood and on Upper Berkeley Street. If a client asked, in that presumptuous way Brits had, “Where are you staying these days?”—meaning where did I live, meaning of what social class and means I was—I could say without hesitation that I lived in Mayfair. If they filled in the blanks in their imagination with an expansive flat with a view, all the better. In point of fact, my flat was so small that I was nearly already halfway through it when I walked in the door; and when I stood in the middle of it, I could reach my arms out and touch either wall.

I kept those details secret, though, and every morning I strolled out of my Mayfair address wearing a fancy old suit of my mother’s knowing that no one would notice much of a difference between me and any trust-fund baby that owned half of the neighborhood.

“I want you to learn how to pitch,” Alexander said to me one day. I’d been talking to clients about the company for months, but in the end, Alexander or Alex Tayler always had to come in to close the deal, so he meant he wanted me to learn to pitch properly, as expertly and as confidently as he did.

Although he was the CEO, Alexander was still the only real salesperson in the company, and his time was ever more in demand. He needed me in the field, he said. I had never stood up in front of a client to make a PowerPoint presentation myself. It was an art, Alexander said, and he would mentor me.

What was most important, he said, was that I learn to sell myself, and that I wow him. I could choose whichever pitch I’d seen him give: the SCL pitch or the Cambridge Analytica one.

At the time, given that I was having little luck closing SCL contracts after the Nigerian deal, it occurred to me I might need to rethink things. I was also becoming increasingly uncomfortable with aspects of SCL’s work in Africa. Many of the African men I met with didn’t respect me or listen to me because I was young and a woman. Also, I was having ethical qualms, as potential deals sometimes lacked transparency or even verged on illegality, I thought. For example, no one ever wanted a paper trail, which meant that most often there were no written contracts. In the rare cases that there were, the contracts weren’t to include real names or the names of recognizable companies. There were always obfuscations, masks, and nebulous third parties. Those arrangements bothered me for ethical reasons as well as selfish ones: every time a deal was less than clean and straightforward, it narrowed my chances of making an argument for what I was owed in commission.

I was learning every day at SCL about other so-called common practices in international politics. Nothing was straightforward. While in discussions regarding freelance election work with contractors for an Israeli defense and intelligence firm, I heard the contractors boast about their firm doing everything from giving advance warning of attacks on their clients’ campaigns to digging up material that would be useful for counter-operations and opposition messaging. At first it seemed pretty benign to me, even clever and useful. The contractors’ firm was pitching clients similar to the SCL Group’s, even with some overlap, and the firm had worked in nearly as many elections as Alexander had. While SCL did not have internal counter-ops capacity, its work still had the feel of guerrilla warfare. The more I learned about each firm’s strategy, both appeared to be willing to do whatever was needed to win, and that gray area started to bother me. I had suggested SCL work with this firm, as I assumed that two companies working together could produce greater impact for clients, but I was quickly taken out of copy, per usual in Alexander’s practice, and not kept abreast of what was actually happening to achieve said results.

While trying to show value and close my first deal, I had introduced this Israeli firm to the Nigerians. I’m not sure what I expected to come of that, besides my looking more experienced than I was, but the results were not what I had imagined they would be. The Nigerian clients ended up hiring the Israeli operatives to work separately from SCL, and as I was later told, they sought to infiltrate the Muhammadu Buhari campaign and obtain insider information. They were successful in this and then passed information to SCL for use. The messaging that resulted discredited Buhari and incited fear, something I wasn’t privy to at the time, while Sam Patten was running the show on the ground. Ultimately, the contractors and SCL itself were not effective enough to turn the tide of the election in Goodluck Jonathan’s favor. To be fair, the campaign hadn’t even lasted a month, but, regardless, he lost spectacularly to Buhari—by 2.5 million votes. The election would become notorious because it was the first time a Nigerian incumbent president had been unseated and also because it was the most expensive campaign in the history of the African continent.

But what was of most concern to me at the time, when it came to ethics, was where the Nigerian money ended up. As I was to learn from Ceris, of the $1.8 million the Nigerian oil billionaire had paid SCL, the team had, in the short time it worked for the man, spent only $800,000, which meant the profit margin for SCL had been outrageous.

The rest of the money I had brought into the company, a cool $1 million, ended up being sheer profit for Alexander Nix. Given that normal markup for projects was 15–20 percent, this was a spectacularly high figure, in my opinion well outside of normal industry standards. It made me wary about pricing for clients in parts of the world where candidates were desperate to win at any cost. While taking high profits is of course legal, it was deeply unethical when Alexander had told the clients we ran out of money and would need more to keep the team on the ground until the delayed election date. I was sure we had more resources, but still, I was afraid to reveal to Alexander that I knew the markup, and the fact that I didn’t confront him on this haunted me.

Frankly, even some of SCL’s European contracts seemed less than aboveboard when I finally paid attention to the details. On a contract SCL had for the mayoral elections in Vilnius, Lithuania, someone in our company forged Alexander’s signature in order to expedite the closing of the deal. I later found out that the deal itself may even have been granted to us in contravention of a national law requiring that election work be publicly tendered and that we had already received notification that we’d “won” the tender before the end of the window of time during which public firms ought to have been able apply for the contract.

When Alexander discovered that his signature had been forged and that the contract wasn’t entirely kosher, he asked me to fire the person responsible, even though she was the wife of one of his friends from Eton. I did what he asked. Later, it would become clear that though he seemed to be punishing the employee for her behavior, what he was angriest about wasn’t the backroom dealing but the fact that she hadn’t collected SCL’s final payment from the political party in question. He made me chase the money and told me to forget about Sam in Nigeria: concentrate on our next paycheck.

All this had started to overwhelm me, and I was nervous that I was in over my head at SCL’s global helm. I began to look elsewhere in the firm for social projects for which I could use my expertise. I had so much to give and so much to learn about data, and I wasn’t going to let some rogue clients get the better of my strong will and put me off from finishing my PhD research.

On the positive side, I was learning that the most exciting innovations were happening in the United States, and that there were dozens of opportunities in America, most of which, thankfully, had nothing to do with the GOP. In Europe, Africa, and many nations around the globe, SCL was limited in its ability to use data because most countries’ data infrastructures were underdeveloped. At SCL, I’d been unable to work on contracts that both made use of our most innovative and exciting tools and that, I believed, involved our best practices.

Alexander had recently boasted of nearly closing a deal with the biggest charity in the United States, so I hopped onto that to help him close it. The work involved helping the nonprofit identify new donors, something that appealed to me greatly, as I had spent so many years in charity fund-raising that I couldn’t wait to learn a data-driven approach to helping new causes. On the political side, SCL was pitching ballot initiatives in favor of building water reservoirs and high-speed trains, public works projects that could really make a difference in peoples’ lives. The company was even moving into commercial advertising, selling everything from newspapers to cutting-edge health care products, an area I could dip into if my heart desired, Alexander told me.

I wanted to learn how analytics worked, and I wanted to do it where we could see, and measure, our achievements, and where people worked with transparency and honesty. I remembered my work with men like Barack Obama. He had been honorable and impeccably moral, and so had the people around him. The way they campaigned was ethical, involving no big-dollar donors and Barack had insisted on absolutely no negative campaigning, too. He would neither attack his Democratic rivals in the primaries nor go low on Republicans. I was nostalgic for a time when I’d experienced elections that ran according to not only rules and laws, but ethics and moral principles.

It seemed to me that my future at the company, if I were to have one, would be in the United States.

I told Alexander I wanted to learn the Cambridge Analytica pitch. And in choosing to do so, I was choosing to join that company, with all the bells and whistles attached.

I couldn’t wow Alexander with my own pitch without first meeting with Dr. Alex Tayler to learn about the data analytics behind Cambridge Analytica’s success. Tayler’s pitch was much more technical and much more involved in the nitty-gritty of the analytics process, but he showed me how Cambridge Analytica’s so-called secret sauce wasn’t one particular secret thing but really many things that set CA apart from our peers. As Alexander Nix often said, the secret sauce was more like a recipe of several ingredients. The ingredients were really baked into a kind of “cake,” he said.

Perhaps the most important first thing that made CA different from any other communications firm was the size of our database. The database, Tayler explained, was prodigious and unprecedented in depth and breadth, and was growing ever bigger by the day. We had come about it by buying and licensing all the personal information held on every American citizen. We bought that data from every vendor we could afford to pay—from Experian to Axiom to Infogroup. We bought data about Americans’ finances, where they bought things, how much they paid for them, where they went on vacation, what they read.

We matched this data to their political information (their voting habits, which were accessible publicly) and then matched all that again to their Facebook data (what topics they had “liked”). From Facebook alone, we had some 570 individual data points on users, and so, combining all this gave us some 5,000 data points on every single American over the age of eighteen—some 240 million people.

The special edge of the database, though, Tayler said, was our access to Facebook for messaging. We used the Facebook platform to reach the same people on whom we had compiled so much data.

What Alex told me helped bring into focus two events I’d experienced while at the SCL Group, the first when I’d just arrived. One day in December 2014, one of our senior data scientists, Suraj Gosai, had called me over to his computer, where he was sitting with one of our research PhDs and one of our in-house psychologists.

The three of them had developed, they explained, a personality quiz called “the Sex Compass”—a funny name, I thought. It was ostensibly aimed at determining a person’s “sexual personality” by asking probing questions about sexual preferences such as favorite position in bed. The survey wasn’t just a joyride for the user. It was, I came to understand, a means to harvest data points from the answers people gave about themselves, which led to the determination of their “sexual personality,” and a new masked way for SCL to gather the users’ data and that of all their “friends,” while topping it up with useful data points on personality and behavior.

The same was true for another survey that had crossed my desk. It was called “the Musical Walrus.” A tiny cartoon walrus asked a user a series of seemingly benign questions in order to determine that person’s “true musical identity.” It, too, was gathering data points and personality information.

And then there were other online activities that, as Tayler explained, were a means to get at both the 570 data points Facebook already possessed about users and the 570 data points possessed about each of the user’s Facebook friends. When people signed on to play games such as Candy Crush on Facebook, and clicked “yes” to the terms of service for that third-party app, they were opting in to give their data and the data of all their friends, for free, to the app developers and then, inadvertently, to everyone with whom that app developer had decided to share the information. Facebook allowed this access through what has become known as the “Friends API,” a now-notorious data portal that contravened data laws everywhere, as under no legislative framework in the United States or elsewhere is it legal for anyone to consent on behalf of other able-minded adults. As one can imagine, the use of the Friends API became prolific, amounting to a great payday for Facebook. And it allowed more than forty thousand developers, including Cambridge Analytica, to take advantage of this loophole and harvest data on unsuspecting Facebook users.

Cambridge was always collecting and refreshing its data, staying completely up to date on what people cared about at any given time. It supplemented data sets by purchasing more and more every day on the American public, data that Americans gave away every time they clicked on “yes” and accepted electronic “cookies” or clicked “agree” to “terms of service” on any site, not just Facebook or third-party apps.

Cambridge Analytica bought this fresh data from companies such as Experian, which has followed people throughout their digital lives, through every move and every purchase, collecting as much as possible in order, ostensibly, to provide credit scores but also to make a profit in selling that information. Other data brokers, such as Axiom, Magellan, and Labels and Lists (aka L2), did the same. Users do not need to opt in, a process by which they agree to the data collection, usually through extensive terms and conditions meant to put them off reading them—so with an attractively easy, small tick box, collecting data is an even simpler process for these companies. Users are forced to click it anyhow, or they cannot go forth with using whichever game, platform, or service they are trying to activate.

The most shocking thing about data that I learned from Alexander Tayler was where it all came from. I hate to break it to you, but by buying this book (perhaps even by reading it, if you have downloaded the e-book or Audible version), you have produced significant data sets about yourself that have already been bought and sold around the world in order for advertisers to control your digital life.

If you bought this book online, your search data, transaction history, and the time spent browsing each Web page during your purchase were recorded by the platforms you used and the tracking cookies you allowed to drop on your computer, installing a tracking device to collect your online data.

Speaking of cookies, have you ever wondered what Web pages are asking when they request that you “accept cookies”? It’s supposed to be a socially acceptable version of spyware, and you consent to it on a daily basis. It comes to you wrapped in a friendly-sounding word, but it is an elaborate ruse used on unsuspecting citizens and consumers.

Cookies literally track everything you do on your computer or phone. Go ahead and check any browsing add-on such as Mozilla’s Lightbeam (formerly Collusion), Cliqz International’s Ghostery, or the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Privacy Badger to see how many companies are tracking your online activity. You could find more than fifty. When I first used Lightbeam to see just how many companies were tracking me, I found that by having visited merely two news Web pages within one minute, I had allowed my data to be connected to 174 third-party sites. These sites sell data to even larger “Big Data aggregators” such as Rocket Fuel and Lotame, where your data is the gas that keeps their ad machines running. Everyone who touches your data along the way makes a profit.

If you are reading this book on your Amazon Kindle, on your iPad, in Google Books, or on your Barnes and Noble Nook, you are producing precise data sets that range from how long you took to read each page, at which points you stopped reading and took a break, and which passages you bookmarked or highlighted. Combined with the actual search terms you used to find this book in the first place, this information gives the companies that own the device the data they need to sell you new products. These retailers want you to engage, and even the slightest hint of what you might be interested in is enough to give them an edge. And all this goes on without your being properly informed or consenting to the process in any traditional sense of the term consent.

Now, if you bought this book in a brick-and-mortar store, and assuming you have a smartphone with GPS tracking switched on—when you use Google Maps, it creates valuable location data that is sold to companies such as NinthDecimal—your phone recorded your entire journey to the bookshop and, upon your arrival, tracked how long you spent there, how long you looked at each item, and even perhaps what the items were, before you chose this book over others. Upon buying the book, if you used a credit or debit card, your purchase was recorded in your transaction history. From there, your bank or credit card company sold that information to Big Data aggregators and vendors, who went on to sell it as soon as they could.

Now, if you’re back home reading this, your robot vacuum cleaner, if you have one, is recording the location of the chair or couch on which you’re sitting. If you have an Alexa, Siri, Cortana, or other voice-activated “assistant” nearby, it records when you laugh out loud or cry while reading the revelations on these pages. You may even have a smart fridge or coffeemaker that records how much coffee and milk you go through while reading.

All these data sets are known as “behavioral data,” and with this data, it is possible for data aggregators to build a picture of you that is incredibly precise and endlessly useful. Companies can then tailor their products to align with your daily activities. Politicians use your behavioral data to show you information so that their message will ring true to you, and at the right time: Think of those ads about education that just happen to play on the radio at the precise moment you’re dropping your kids off at school. You’re not paranoid. It’s all orchestrated.

And what’s also important to understand is that when companies buy your data, the cost to them pales in comparison to how much the data is worth when they sell advertisers access to you. Your data allows anyone, anywhere, to purchase digital advertising that targets you for whatever purpose—commercial, political, honest, nefarious, or benign—on the right platform, with the right message, at the right time.

But how could you resist? You do everything electronically because it’s convenient. Meanwhile, the cost of your convenience is vast: you are giving one of your most precious assets away for free while others profit from it. Others make trillions of dollars out of what you’re not even aware you are giving away each moment. Your data is incredibly valuable, and CA knew that better than you or most of our clients.

When Alexander Tayler taught me what Cambridge Analytica could do, I learned that in addition to purchasing data from Big Data vendors, we had access to our clients’ proprietary data, aka data they produced themselves that was not purchasable on the open market. Depending on our arrangements with them, that data could remain theirs or it could become part of our intellectual property, meaning that we could retain their proprietary data to use, sell, or model as our own.

It was a uniquely American opportunity. Data laws in countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, and France don’t allow such freedoms. That’s why America was such fertile ground for Cambridge Analytica, and why Alexander had called the U.S. data market a veritable “Wild West.”

When Cambridge Analytica refreshed data, meaning updating the locally held database with new data points, we struck a range of agreements with clients and vendors. Depending on those agreements, the data sets could cost either in the millions of dollars or nothing, as Cambridge sometimes struck data-sharing agreements by which we shared our proprietary data with other companies for theirs. No money had to change hands. An example of this comes from the company Infogroup, which has a data-sharing “co-op” that nonprofits use to identify donors. When one nonprofit shares with Infogroup its list of donors, and how much each gave, it receives in return the same data on other donors, their habits, fiscal donation brackets, and core philanthropic preferences.

From the massive database that Cambridge had compiled from all these different sources, it then went on to do something else that differentiated it from its competitors. It began to mix the batter of the figurative “cake” Alexander had talked about. While the data sets we possessed were the critical foundation, it was what we did with them, our use of what we called “psychographics,” that made Cambridge’s work precise and effective.

The term psychographics was created to describe the process by which we took in-house personality scoring and applied it to our massive database. Using analytic tools to understand individuals’ complex personalities, the psychologists then determined what motivated those individuals to act. Then the creative team tailored specific messages to those personality types in a process called “behavioral microtargeting.”

With behavioral microtargeting, a term Cambridge trademarked, they could zoom in on individuals who shared common personality traits and concerns and message them again and again, fine-tuning and tweaking those messages until we got precisely the results we wanted. In the case of elections, we wanted people to donate money; learn about our candidate and the issues involved in the race; actually get out to the polling booths; and vote for our candidate. Likewise, and most disturbing, some campaigns also aimed to “deter” some people from going to the polls at all.

As Tayler detailed the process, Cambridge took the Facebook user data he had gathered from entertaining personality surveys such as the Sex Compass and the Musical Walrus, which he had created through third-party app developers, and matched it with data from outside vendors such as Experian. We then gave millions of individuals “OCEAN” scores, determined from the thousands of data points about them.

OCEAN scoring grew out of academic behavioral and social psychology. Cambridge used OCEAN scoring to determine the construction of people’s personalities. By testing personalities and matching data points, CA found it was possible to determine the degree to which an individual was “open” (O), “conscientious” (C), “extroverted” (E), “agreeable” (A), or “neurotic” (N). Once CA had models of these various personality types, they could go ahead and match an individual in question to individuals whose data was already in the proprietary database, and thus group people accordingly. So that was how CA could determine who among the millions upon millions of people whose data points CA had were O, C, E, A, N, or even a combination of several of those traits.

It was OCEAN that allowed for Cambridge’s five-step approach.

First, CA could segment all the people whose info they had into even more sophisticated and nuanced groups than any other communications firm. (Yes, other companies were also able to segment groups of people beyond their basic demographics such as gender and race, but those companies, when determining advanced characteristics such as party affinity or issue preference, often used crude polling to determine where people generally stood on issues.) OCEAN scoring was nuanced and complex, allowing Cambridge to understand people on a continuum in each category. Some people were predominantly “open” and “agreeable.” Others were “neurotic” and “extroverts.” Still others were “conscientious” and “open.” There were thirty-two main groupings in all. A person’s “openness” score indicated whether he or she enjoyed new experiences or was more inclined to rely on and appreciate tradition. The “conscientiousness” score indicated whether a person preferred planning over spontaneity. The “extroversion” score revealed the degree to which one liked to engage with others and be part of a community. “Agreeableness” indicated whether the person put others’ needs before their own. And “neuroticism” indicated how likely the person was to be driven by fear when making decisions.

Depending on the varied subcategories in which people were sorted, CA then added in the issues about which they had already shown an interest (say, from their Facebook “likes”) and segmented each group with even more refinement. For example, it was too simplistic to see two women who were thirty-four years old and white and who shopped at Macy’s as the same person. Rather, by doing the psychographic profiling and then adding to it everything ranging from the women’s lifestyle data to their voting records to their Facebook “likes” and credit scores, CA’s data scientists could begin to see each woman as profoundly different from the other. People who looked alike weren’t necessarily alike at all. They therefore shouldn’t be messaged together. While this seems obvious—it was a concept supposedly already permeating the advertising industry at the time Cambridge Analytica came along—most political consultants had no idea how to do this or that it was even possible. It would be for them a revelation and a means to victory.