По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

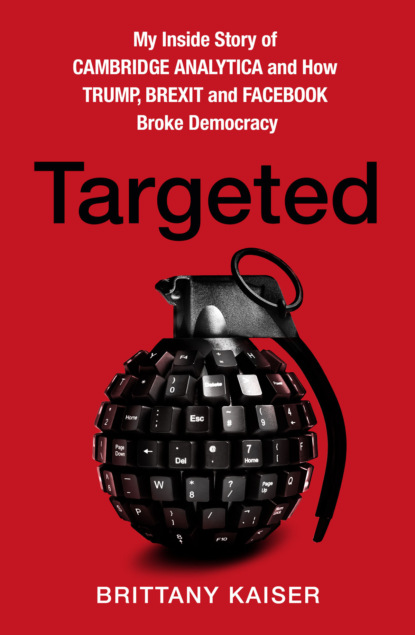

Targeted: My Inside Story of Cambridge Analytica and How Trump, Brexit and Facebook Broke Democracy

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

And we spread salt to prevent the guests from slipping.

Indoors, I hung the banners and helped lay out the food. Here and there, I laid down business cards of my own and SCL brochures.

Alexander and John Jones were early arriving. They were thrilled to be there. Neither had been in Davos before.

I stood at the door and welcomed guests. Each was more famous than the last: the entrepreneur Richard Branson, Ross Perot Sr. and Jr., members of the Dutch royal family, and at least a hundred others. They spilled out onto the terrace, where they watched the bartenders performing magic tricks, mixing cocktails and juggling with fire. Inside, in the middle of the living room, they stood around watching a giant demonstration that the aspiring asteroid miners had set up: a model of an asteroid atop of which was perched a contraption that looked like a tripod and was meant to resemble something like an oil rig.

Milling among the guests, John Jones looked happy. While Alexander clearly felt that SCL was in a far smaller class than the other businesses represented in the room, he was glad to have the chance to network, and he was particularly happy to see Eric Schmidt, the CEO of Google. Before he ventured over to Schmidt, he shared with me that it was Sophie Schmidt, Eric’s daughter, who had been partly responsible for inspiring the inception of Cambridge Analytica.

The party was going swimmingly until my phone buzzed: the Nigerians had arrived and were downstairs, just outside the apartment building.

We had planned a literally flashy welcome for them. When they landed at Zurich airport, a limo was waiting for them, and on the drive into town, they were accompanied, in front of the limo and behind, by police cars, sirens blaring and lights flashing, announcing the arrival of visitors of significance.

But when the Nigerians reached me by phone, they weren’t pleased.

They were hungry. Where was their dinner?

I had invited them to the party; there was plenty of food there, I told them. Chester and I had spent hundreds of dollars of our budget on it.

No, they said; they were tired. They wanted to eat, be shown their lodgings, and go to bed. They weren’t interested in coming to a party. They had not eaten on the plane—a twelve-hour flight—and they wanted, they said, fried chicken. I would need to find it somewhere and bring it to them.

I had no choice but to throw on my boots and coat and head down to meet them on the icy streets below. They were standing outside the apartment building, where people were still lining up to get into my party. All five men again claimed they couldn’t possibly go upstairs and were demanding to be fed, chicken preferably.

I explained that we wouldn’t be able to drive anywhere to get it—the limo wasn’t allowed in the central area. Walking was the only choice, so I led them through the streets in the bitter cold.

They weren’t prepared for the weather. They had neither boots nor coats. They wore thin collared shirts and flat loafers. We slipped and slid, walking from closed restaurant to closed restaurant, finding, of course, no fried chicken in a Swiss mountain town, and little else as well. Finally, I happened upon a restaurant that served pasta atop of which the chef agreed to put some grilled chicken. Takeout containers in hand, I led the Nigerians back onto the slippery streets again, the men, freezing, following along behind me, barely able to stay upright. I carried the stack of chicken-and-pasta meals all the way to their lodgings, where I made sure they were settled in, and I said my good-nights. They looked cold, hungry, and far more unhappy with me than I would have liked.

I was away from the party for almost two hours. When I got back, it was 2:00 a.m., and the party was still raging.

Chester was nowhere to be found. No one had been at the door to welcome guests. No one had been in charge. The bartenders had run out of alcohol. The food had been devoured. Just before I returned, the guests had become rowdy, and a drunken princess had fallen outside and, though unhurt, was making an inebriated ruckus that had set off alarms.

For the second time that night, the air filled with the sound of sirens and the flash of spinning lights. The Swiss Police were on their way to stop the party. With the help of the son of the head of police, we managed to talk them out of arresting anyone, but not in stopping the party.

When the interaction was over, I stood in the middle of the empty room. I was starving. Like the Nigerians, I hadn’t eaten for hours.

Alexander was as pleased with the results of Davos as he was of the deal I had made with the Nigerians. He had found the party festive. He had met people he wouldn’t otherwise have, and of course SCL had walked away with a giant fishbowl full of business cards from some of the wealthiest and most influential people in the world.

What he didn’t know yet was how disastrous the evening had been for our relationship with our Nigerian clients, and how angry they were the next morning when they woke to discover that Alexander had flown back to London without even bothering to meet them.

When they learned that he was gone, they demanded that I come to see them immediately. They didn’t want to go out themselves. It was too cold.

So, I made my way through the slippery streets in my inadequate boots, cringing.

I’d never been yelled at by an African billionaire before. He and the other Nigerians didn’t understand why they weren’t being treated better. They were VIPs, they said, just as important as the other VIPs at the conference. Why had no reception been arranged especially for them? Why hadn’t the CEO of my company, to which they had just paid nearly $2 million, stayed to meet them? They were unhappy, too, with the work we were doing in Nigeria. Where were the radio spots? Where were all the billboards? What’s our money going toward? they demanded to know.

I didn’t know how to reason with them. They had never invested in an election before. They didn’t know what to expect. Perhaps they had thought they would see a giant rally on the back of a truck with LED screens flashing and megaphones blasting. That hadn’t been part of the team’s plan. Measuring the impact of elections work is a complicated task, and, having been a part of the company for just over a month, I couldn’t explain to them right then and there why everything SCL had done wasn’t more obvious to the naked eye. The fruits of SCL’s labors might be borne out only on Election Day in March, and they needed to be patient.

But they wouldn’t listen to me. It wasn’t just that I was young; it was also that I was a woman. This attitude was eminently clear, and made me incredibly uncomfortable. It even began to feel threatening. These were powerful, wealthy men, the kind who thought nothing of filling a jet with naira, the Nigerian currency. What might they be capable of if they were unhappy with how that money had been spent?

When I put them on a conference call with Alexander, they were calmer, and much more respectful. They didn’t yell, but they weren’t assuaged. Yet Alexander seemed oblivious to how serious the situation was.

I arranged for John Jones to come over and visit with them. Perhaps they could find a way of working together. We discussed strategies for showing up Buhari in the press and making his alleged war crimes known, but when I left the Nigerians with him to head back to our apartment, I had the sinking feeling that there would be no second contract after February 14. The Nigerians hadn’t said as much, but the way they’d treated me was demeaning. How could I possibly return to them and close another contract? Things were trending in a bad direction, and even worse, while taking care of them, I’d had no time even to pursue any SCL leads, so the trip would not even result in new business.

As if all that weren’t bad enough, that morning the website Business Insider published a story about the evening before: “Davos Party Shut Down After Bartenders Blow Through Enough Booze for Two Nights,” the headline read.

When the phone rang, it was Alexander. Maybe he had seen the article. Even if my name wasn’t in it, it could look bad for SCL. Maybe the Nigerians had called to give him a piece of their minds.

But he was buoyant. Neither had happened, it seemed.

“Brittany,” he said. “Davos was wonderful. Thanks to you and Chester for the excellent hosting! I’m calling to let you know that I’m offering you a permanent position with SCL that you’ve been waiting for!” he said, likely winking on the other end of the phone. “No more consulting. You’ll be a full member of the team.”

There’d be a bonus, he added: ten thousand dollars more per year; a regular salary, benefits; a company credit card. I could pursue the types of projects I liked, as long as they brought in the same kind of money as the Nigerian campaign. It was a high bar, but it had been an auspicious start.

Welcome aboard, he said.

5 (#ulink_6e7fda59-c1d0-5c52-ad68-0b12e63aba7a)

Terms and Conditions (#ulink_6e7fda59-c1d0-5c52-ad68-0b12e63aba7a)

FEBRUARY–JULY 2015

It didn’t take long for full-time employment at SCL to afford me entry into the higher echelons of the company. In an email copying only a handful of people—Pere, Kieran, Sabhita, Alex Tayler, and me—employees whom Nix considered important and “good fun,” he said, he invited us out for lunch one weekend at his home in Central London.

Located in Holland Park, it was a city house—he had a country one as well—a four-story stone mansion, the interior of which resembled a private members-only club or rooms you would find in Buckingham Palace, except that the art that hung from ceiling to floor weren’t Old Masters but, instead, provocatively modern.

We started at midday with vintage champagne in the drawing room and continued at the dining table for hours, all through which the champagne flowed. Alexander and the others told war stories about their time together in Africa. In 2012, for example, Alexander had moved a team from SCL and his entire family to Kenya, so that he could run the country’s 2013 election himself. He hadn’t too many staff members at the time, and it had been difficult. Research was limited to door-to-door surveys, and messaging was done through roadshows on those convertible stage-trucks I’ve mentioned before.

“That’s why what we’re doing in America is so incredibly exciting,” Alexander said. “Knocking on doors isn’t the only way to get data now. Data is everywhere. And every decision is now data-driven.”

We stayed at his house until dinnertime, and then all of us, woozy and lightheaded, made our way to a bar somewhere for cocktails, and then for a meal somewhere else, and then to another bar, where we capped off the evening.

It was the kind of memorable event that is difficult to recollect entirely the next day, although in the office, I began to see that Alexander’s excitement about America was more than just idle chat over drinks.

Indeed, while I continued to pursue global projects, my colleagues at SCL were increasingly focused on the United States, and their work was no longer confined to the Sweat Box. They were absorbed in daily conversations I could overhear, about their client Ted Cruz. He had signed on with us back in late 2014, for a small contract, but was now upgrading to nearly $5 million in services. Kieran and the other creatives were now producing tons of content for the Texas senator. They huddled at a desktop computer putting together ads and videos, which they would sometimes show off and at which they would sometimes stare, grimacing.

Meanwhile, Alexander was focused entirely on the United States, too. The Cruz campaign had agreed to sign a contract without a noncompete clause, so Alexander was free to pursue other GOP candidates as well. Soon, he had signed Dr. Ben Carson. Next up, he began systematically pitching the rest of the seventeen Republican contenders. For a while, Jeb Bush considered hiring the firm; Alexander said Jeb even flew to London to meet with him. In the end, though, he wanted nothing to do with a company that would even consider working at the same time for his competition. The Bushes were the kind of family who demanded single-minded loyalty from those with whom they worked.

The Cambridge Analytica data team busied themselves preparing for the 2016 U.S. presidential election by interpreting the results of the 2014 midterms. In their glass box, they wrote up case studies from John Bolton’s successful super PAC operation, from Thom Tillis’s senatorial campaign, and from all the North Carolina races. To show how Cambridge had succeeded, they put together a packet explaining how they’d broken the target audience into “Core Republicans,” “Reliable Republicans,” “Turnout Targets,” “Priority Persuasions,” and “Wildcards,” and how they’d messaged them differently on issues ranging from national security to the economy and immigration.

Also, in the data analytics lab, Dr. Jack Gillett produced midterm data visualizations—multicolor charts, maps, and graphics to be added to new slide shows and pitches. And Dr. Alexander Tayler was always on the phone in search of new data from brokers all over the United States.

I was still pursuing SCL projects abroad, but as Cambridge Analytica ramped up for 2016, I was becoming privy, if accidentally, to confidential information, such as the case studies, the videos, the ads, and the chatter around me. I was never copied on CA emails at that time, but there were stories in the air and images on nearby computer screens.

This presented an ethical dilemma. The previous summer, when Allida Black, founder of the Ready for Hillary super PAC was in town, I’d been fully briefed on Democratic Party plans for the election. Now I was receiving a regular paycheck from a company working for the GOP. It didn’t sit well with me, and I knew that it wouldn’t sit well with others.

No one asked me to, but I began to cut my ties with the Democrats, although I was too embarrassed to tell anyone on the Democratic side why. I didn’t want to put the SCL Group on my LinkedIn or Facebook page. I didn’t want any Democratic operatives I knew to have to worry that I’d ever use information I had from them against them. Eventually, I stopped replying to incoming emails from the Ready for Hillary super PAC and from Democrats Abroad, and I made sure that in writing personally to friends who were Democrats, I never included the SCL name on any of my communications. To the Clinton teams, it must have seemed as though I had simply dropped off the map. It wasn’t easy for me to do. I was tempted to read everything that came in, news about exciting meetings and plans. So, after a while, I just let these messages sit in my in-box, unopened, relics of my past.

I also didn’t want my Cambridge Analytica colleagues or the company’s GOP clients to worry about the same. After all, I was a Democrat working in a company that exclusively served Republicans in the United States. I removed the Obama campaign and the DNC from my LinkedIn profile (my public résumé) and erased all other public references I had made to the Democratic Party or my involvement in it. This was painful, to say the least. I also begrudgingly stopped using my Twitter account, @EqualWrights, a catalog of years of my left-leaning activist proclamations. As much as it hurt to close those doors and hide some of the most important parts of myself, it was necessary, I knew, in order for me to grow into the professional political technology consultant I was to become. And one day, perhaps, I could reopen both those accounts and that part of myself.