По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

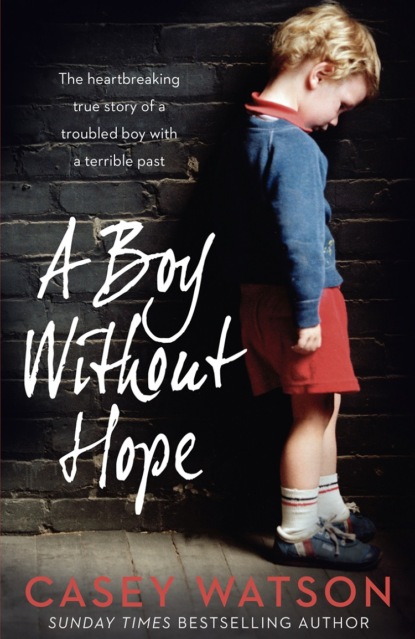

A Boy Without Hope

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I’m still not sure, love,’ I told Mike. ‘I think it might depend on how settled I feel when we meet this new woman. I mean, we’ve been so lucky to have had John for so many years, and that he felt the same as we do. I’m just hoping she’s of a similar mindset, that’s all.’

‘And if she isn’t?’ Mike asked

‘Well, we’ll just have to see,’ I said. And I meant it. ‘I know I’m impulsive. I know I sometimes act first and think later. But I really will put a lot of thought into it before deciding.’

‘Well, that’ll be a first,’ he said. ‘But you know what? I don’t think you’ll need to. This is one of those times where I think your instinct will – and should – lead the way. Hey,’ he added, reaching for the matches so he could light the scented candle I’d dug out. ‘Maybe she’ll be a tea drinker! Then you won’t have to think at all, will you?’

Which comment made it all but impossible for me not to explode into nervous laughter, when, ten minutes later, our new visitor responded to my usual opening gambit of ‘Drink? Tea or coffee?’ with ‘Oh, tea for me, please – every time.’

I might have done, too, had John not beaten me to it, along with a jaunty ‘Forgot to tell you, Casey – Christine hails from the dark side.’

Though in truth, a tea drinker was exactly what she looked like. Which, bizarrely, given my prejudices, was something of a comfort. Yes, she was dressed in a sharp skirt and jacket suit, and there was no denying that she looked ready for business, with her fair hair perfectly blowdried and her big leather laptop case, and the label – Ms C. Bolton – on a folder she’d pulled out, but there was at least something approachable about her that I hadn’t anticipated, enhanced by her soft Liverpudlian accent, and her readiness to accept a chocolate chip cookie, which she dunked in her tea while John went through his spiel. You couldn’t mistrust a dunker, could you?

Having never been through a change-over of fostering link worker before, I had no idea how these things usually went. Though I didn’t doubt there would be a protocol – there was a protocol for everything. But it turned out there wasn’t – not in my house, at any rate. Such official handing over of responsibilities as needed to happen had already happened. And would continue to do so, John explained, over the next couple of weeks, during which time Christine would shadow him in his various duties.

And this was one such – no more than an unofficial ‘meet and greet’, really. One where I had the bizarre notion that the poor woman was having to repeat herself endlessly, in a series of thinly veiled ‘pitches’ to John’s stable of carers, as if she was on The Apprentice or something, having to go from house to house, laying out her credentials over endless cups of tea. I wondered how far along the line we were. She certainly seemed to have memorised her script.

‘John speaks very highly of you both,’ she said as she daintily sipped her tea. ‘So I’m very much looking forward to us working together. I’m also hoping that both of you might be something of a crutch for me, while I’m finding my way around the way things work here. All those boring procedures and so on.’

I laughed politely. ‘Likewise,’ I told her. ‘But I’m sure John’s also told you I’m a bit of a scatterbrain, so I doubt I’d be much use as a crutch. In fact, if I’m honest,’ I rattled on, ‘I’m usually the one who’s battling against procedure’ – I grinned at John – ‘more often than the other way around.’

John spluttered slightly. ‘That’s not true at all, Christine,’ he said. ‘Yes, Casey does sail a little close to the wind at times, as I’m sure she’ll be the first to admit. But as I explained on the way here’ – he grinned back at me – ‘that’s only because she cares. She’s fiercely protective of the children she looks after for us, and will fight tooth and nail to be their advocate if she feels there’s any injustice. But that’s one of her great strengths. Am I right, Mike?’

Mike nodded. I blushed, feeling Christine’s eyes on me. Feeling scrutinised. I wondered what else they’d already discussed. ‘And I’m sure you’ll soon get the hang of things, Christine,’ Mike said. ‘And you’ll love working over this end. We’re not a bad bunch round here. What about your own family? How are they finding the relocation?’

‘No family. Just myself and my husband Charles,’ she answered. ‘He’s an accountant, and he does a lot of work from home, which makes it easier. Which it needs to be, given how erratic my hours can be, of course.’

She smiled. I smiled back. So it looked like they were childless. Which didn’t make any difference. It shouldn’t, and it wouldn’t. Some of the most remarkable advocates for and defenders of children were able to be so precisely because they didn’t have their own. I judged her to be in her mid-forties or thereabouts. I wondered if it was a case of not wanted, not yet, or not able. Then checked myself – these were thoughts that wouldn’t have even occurred to me had a man been sitting across from me – and that was food for thought in itself. But perhaps being female made it difficult not to have them. As a person blessed (or cursed) with a strong maternal urge, I was always interested in women’s choices, and how they made them. Or, in the case of so many of the kids we had fostered, how those choices were taken away from them. I wondered what had brought Christine Bolton into the world of care and children.

It sounded as if she had other things to worry about, however. ‘The main thing is that we’re closer to my husband’s parents,’ she said. ‘He’s an only child and his father has Alzheimer’s,’ she explained. ‘Being closer means he’ll be able to help his mum out a lot more. You probably know what it’s like.’ We all nodded, in unison. Was there a family around not impacted by dementia? I counted my blessings that my own parents, both now in their late seventies, had so far been spared.

‘That must be tough,’ I said. ‘But, as you say, being closer will make things easier. And here’s hoping you’ll have the space to ease into work gently, so you can get yourself orientated and settled in.’

At which point John coughed. And Christine Bolton looked across at him. I’m no Sherlock Holmes, but I clocked it immediately. I caught his eye.

‘So,’ he said, ‘does anyone have any questions?’

Only one unspoken one, I thought. What’s going on? I looked across at Mike, who was rising from his chair, ready to say his goodbyes and head for work. And I could tell he was wondering that too. And when John retrieved his case from where he’d parked it under the table, Mike sat down again. ‘I have,’ he said to John. ‘And it’s “And?”’

John had the grace to look guilty. Though, actually, not that guilty. Because, given that he was leaving, why would he? He pulled a manila file, smooth as silk, from his trusty bag.

He looked at me. ‘You don’t have to say yes, Casey,’ he said as he held it up. ‘And I’m not playing games with you, I promise,’ he added, having read my expression (something he was obviously good at) and correctly interpreting it as one of irritation that what he’d been doing was exactly that.

‘A child,’ Mike said, nodding towards the unopened file.

‘A twelve-year-old boy,’ John said. ‘Name of Miller Green. And this literally landed on my desk only this morning, or of course I’d have phoned you and told you both. We’ve barely even had a chance to have a read through of all the notes, have we?’ he added, glancing at his now professionally grim-faced successor. ‘And I obviously didn’t want to welly straight on into it till you and Christine had had a chance to get acquainted. So …’

‘Sounds fair enough,’ Mike said mildly. ‘What’s the story?’

‘First thing is that this doesn’t sound like an easy one,’ John admitted. ‘So you’ll have to think hard before agreeing to it, okay? And I mean that.’ He tapped the file. ‘This looks like one challenging kid.’

At which point I’d have normally thought bring it on. I didn’t. ‘So?’ I asked instead. ‘What’s his background?’

John donned his reading glasses and skimmed through what he’d obviously identified at the key facts. ‘A really sad case, it seems. Poor kid was first known to social services when he was found playing on a railway crossing, adjacent to a busy road, almost seven years ago. Almost naked, etc., etc., police called to investigate, parents didn’t want him – they’re both long-term substance abusers, apparently. The boy’s been in care ever since. But a huge number of placement breakdowns. And I mean huge. From what I can gather, there’s also a pattern. Always seems to feel the need to destroy it almost before it starts.’ John glanced at me from over his glasses. ‘Frequently described as being “difficult to like”.’

He’d freighted the last three words with heavy, deliberate meaning. ‘And where is he now?’ I asked.

‘Currently with a foster couple called Jenny and Martin in another county,’ John said. ‘Martin works away during the week, and Jenny can no longer cope. The boy has been excluded from – it says here – “yet another school, and is not at the moment in education”. Jenny wants him gone as soon as possible. Ideally today.’

’Wow!’ I said. ‘I know you’re not trying to put me on the spot, but this really is a decision that needs making, like, now, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, it does,’ John admitted. ‘Though, given what we do know about the boy, and his previous history, plus the fact that he’s currently out of education, we don’t expect you to make a long-term commitment right away. All we’re after is a commitment to giving it a proper shot. See how things go, say, for starters, on a month-by-month basis. Well supported, of course. You know you can depend on that.’

A proper shot, I thought. As if we’d ever commit to anything less! But well supported? Without John? And by this brisk, slightly stiff woman?

‘Well, of course,’ I said. ‘Obviously. But –’

Then Christine jumped in. ‘But we completely understand if you think it might be too big an ask for you. I mean given his age – and let’s face it, none of us are getting any younger, are we? Please feel free to say no, and we can keep the door open for you to take on a child who doesn’t come accompanied with quite so many challenges.’

I stared at John in disbelief. In fact, I think my mouth hung open for a good twenty seconds. Too big an ask? None of us were getting any younger? Take on a child without quite so many challenges? Cheeky mare!

A part of me accepted that she was just covering the bases. If she sensed any hesitation, it was right that she did, too. It would be insane to place a child with carers any less than 100 per cent willing. Placement breakdowns were damaging. And it seemed this kid had already suffered quite a few.

But, whether she was aware of it or otherwise, her words had hit a nerve. Needless to say, if there was one thing I always rose to, it was a challenge. In this case, the challenge of correcting Ms Bolton in the matter of the impression she had obviously already formed about me. So it was that I opened my mouth before engaging my brain. ‘We’ll do it,’ I said firmly. ‘He sounds right up my street.’

Chapter 3 (#u6dcccb14-42e2-5a8b-93a4-a0734658d271)

They’d said they’d be with us at 6.30 p.m., and it was now almost seven. So my initial reservations about Christine Bolton had now been replaced with the familiar feeling of nervous anticipation I always had before a new child arrived.

Though she had indeed ruffled my feathers earlier in the day, even if not in the way I had expected. It was only after she and John had left us that it occurred to me that I might have been ‘played’ – as Tyler might put it. That her gestures of concern about whether Mike and I felt up to such a challenge might have been expressly designed to ensure that I couldn’t help but rise to it. A laying down of a gauntlet that I couldn’t resist picking up. If so, she already knew me better than she realised.

So I’d put myself here, in short. Just as I had convinced myself that I could easily walk away from fostering and find something else to keep me occupied, a huge spanner had consequently been thrown in the works – one which would certainly force me to put any thoughts of leaving on the back burner. And for me, that wasn’t an ideal situation to be in at all. I hated having a ‘should I, shouldn’t I’ scenario playing out somewhere in the back of my mind. It would gnaw away at me during any quiet moments, I just knew it.

The truth was, of course, that I could, and perhaps should, have said no. I could have explained that I’d been having doubts about our future as foster carers, and that at this point – at least till I’d worked my concerns through in my head – I wasn’t ready to take on another child, particularly one flagged as particularly difficult to manage. They would have understood. I knew that. They would have offered to support me. There was no point in less than 100 per cent commitment, after all. That was true for them as much as me.

But even knowing little about this child they were so desperate to place, the fact that he was real now – no longer a potential child, but an actual one – was already messing with my head. It would no longer be a case of turning down a hypothetical child. I’d be turning down a specific one, which felt very different. My decision to do so wouldn’t just be removing us from the agency register. It would mean refusing to take a real child, with very real, possibly grave, consequences for him. No, he wouldn’t know that, but I would.

Which was my right. And, given my ambivalence, perhaps the right thing to do anyway, but I couldn’t help my mind from returning to Justin, the very first child we’d agreed to foster, over a decade back and, in some ways, one of the most challenging, because of that. We had helped turn his life around, and back when we were still very inexperienced. Now we had all that experience under our belts, wouldn’t we be even better placed to offer the support and guidance this child clearly needed? The similarities between the boys resonated too. Here was another lad knocking on the door of that ‘last chance saloon’, with another string of failed placements making him increasingly hard to place. Abandoned, both by his parents, and – at least as good as – by the system. Did I want my name to be added to the growing list of people who’d turned away? Could I? I wasn’t sure I could. Perhaps I just needed to meet him. Perhaps my gut would tell me. I hoped so.

‘A case of que sera, I suppose,’ I said aloud, even if more to myself than anyone else. But it caused both Mike and Tyler to grin in mild amusement. ‘What?’ I said, going to peep out of the window for the umpteenth time. ‘Don’t the pair of you ever talk to yourselves these days?’

We’d bought Tyler a guitar for his sixteenth birthday, the better to further his dream of becoming a famous singer-songwriter (well, in his free time from being a famous footballer, obviously), and in the few months he’d had it, he’d already become quite good. He was also having lessons, and had impressed us with his diligence in practising; we’d often hear the sound of repetitive twanging coming from his bedroom, accessorised by the odd curse when he played a wrong chord. He was strumming it now, swaying on a dining chair as he played, channelling Ed Sheeran, as was his current habit. ‘And we all watched … as she slowly went insane, yeah, yeah …’

Mike roared with laughter. ‘Is that the new song you’re writing, son?’ he asked, quickly taking refuge in the dining area, where he’d be safely out of my reach.

‘Oh, very funny,’ I said, shaking my head at the two of them. I glanced at the clock again. ‘It’s now gone seven,’ I pointed out. ‘What’s going on?’

‘Maybe the kid’s run off,’ Tyler suggested. ‘Didn’t you say that was one of his things, running away? Maybe he’s decided he doesn’t want another move and has run away to join a circus.’