По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

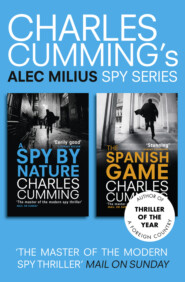

The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

With coffee, the waiter brings us two small shots of lemon liqueur–on the house–and we down them in a gulp. Saul is keen to pay (‘as a present, for putting me up’) and I feel mildly drunk as we make our way out past the kitchen and into the bustle of Chueca. It is past midnight and the nightlife is well under way.

‘You know a decent bar?’ he asks.

I know plenty.

SEVEN

Churches

Spaniards dedicate so much of their lives to enjoying themselves that a word actually exists to describe the span of time between midnight and 6 a.m., when ordinary European mortals are safely tucked up in bed. La madrugada. The hours before dawn.

‘It’s a good word,’ Saul says, though he thinks he’ll be too drunk to remember it.

We leave Chueca and walk west into Malasaña, one of the older barrios in Madrid, still a haunt of drug dealers and penniless students though, by reputation, neither as violent nor as rundown as it was twenty years ago. The narrow streets are teeming and dense with crowds that gradually thin out as we head south in the direction of Gran Vía.

‘Haven’t we just been here?’ Saul asks.

‘Same neighbourhood. Further south,’ I explain. ‘We’re going in a circle, looping back towards the flat.’

A steep hill leads down to Pez Gordo, a bar I love in the neighbourhood, favoured by a relaxed, unostentatious crowd. There’s standing room only and the windows are fogged up with posters and condensation, but inside the atmosphere is typically rousing and flamenco music rolls and strums on the air. I get two cañas within a minute of reaching the bar and walk back to Saul, who has found us a spot a few feet from the door.

‘Do you want to hear my other theory?’ he says, jostled by a customer with dreadlocked hair.

‘What’s that?’

‘I know the real reason you like living out here.’

‘You do?’

‘You thought that moving overseas would give you a chance to wipe the slate clean, but all you’ve done is transfer your problems to a different time zone. They’ve followed you.’

Here we go again.

‘Can’t we talk about something else? It’s getting a little tedious, all this constant self-analysis.’

‘Just hear me out. I think that some days you wake up and you want to believe that you’ve changed, that you’re not the person you were six years ago. And other times you miss the excitement of spying so much that it’s all you can do not to ring SIS direct and all but beg them to take you back. That’s your conflict. Is Alec Milius a good guy or a bad guy? All this paranoia you talk about is just window-dressing. You love the fact that you can’t go home. You love the fact that you’re living in exile. It makes you feel significant.’

It amazes me that he should know me so well, but I disguise my surprise with impatience.

‘Let’s just change the subject.’

‘No. Not yet. It makes perfect sense.’ He’s toying with me again. A girl with a French accent asks Saul for a light, and I see that his nails are bitten to the quick as she takes it. He’s grinning. ‘People have always been intrigued by you, right? And you’re playing on that in this new environment. You’re a mysterious person, no roots, no past. You’re a topic of conversation.’

‘And you’re pissed.’

‘It’s the classic expat trap. Can’t cope with life back home, make a splash overseas. El inglés misterioso. Alec Milius and his amazing mountain of money.’

Why is Saul thinking about the money?

‘What did you say?’

A momentary hesitation, then, ‘Forget it.’

‘No. I won’t forget it. Just keep your voice down and explain what you meant.’

Saul grins lopsidedly and takes off his coat. ‘All I’m saying is that you came here to get away from your troubles and now they’ve passed you by. It’s time for you to move on. Time for you to do something.’

For a wild moment, undoubtedly reinforced by alcohol, it crosses my mind that Saul has been sent here to recruit me, to lure me back into Five. Like Elliott sent to Philby in Lebanon, the best friend dispatched at the state’s request. His angle certainly sounds like a pitch, although the notion is ridiculous. More likely Saul is simply adhering to that part of his nature that has always annoyed me and which I had somehow allowed myself to forget; namely, the moralizing do-gooder, the self-righteous evangelist busily saving others whilst incapable of saving himself.

‘So what do you suggest I do?’

‘Just come home. Just put an end to this phase of your life.’

The idea is certainly appealing. Saul is right that there are times when I look back on what happened in London with nostalgia, when I regret that it all came to an end. But for Kate’s death and the exhaustions of secrecy, I would probably do it all again. For the thrill of it, for the sense of being pivotal. But I can’t state that directly without appearing insensitive.

‘No. I like it here. The lifestyle. The climate.’

‘Seriously?’

‘Seriously.’

‘Well then, at least don’t change your mobile phone every three weeks. And just get one email address. Please. It pisses me off and annoys your mum. She says she still doesn’t know why you’re out here, why you don’t just come home.’

‘You’ve talked to Mum?’

‘Now and again.’

‘What about Lithiby?’

‘Who’s Lithiby?’

If Saul is working for them, they have certainly taught him how to lie. He runs his finger along the wall and inspects it for dust.

‘My case officer at Five,’ I explain. ‘The guy behind everything.’

‘Oh, him. No, of course not.’

‘He’s never been to see you?’

‘Never.’

Someone turns the music up beyond a level at which we can comfortably speak, and I have to shout at Saul to be heard.

‘So where did you put the disks?’

He smiles. ‘In a safe place.’

‘Where?’