По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

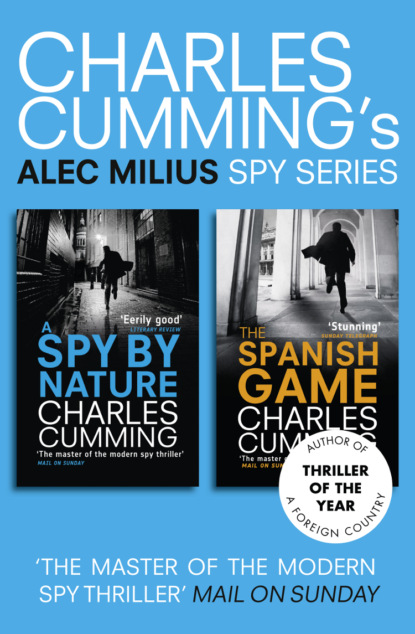

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘About two months ago. I just had a bout of feeling unstretched, needed to take some action and sort my life out.’

‘What, so you want to be a diplomat?’

‘Yeah.’

It doesn’t feel exactly wrong to be telling him this. At some point in the next eighteen months, a time will come when I may be sent overseas on a posting to a foreign embassy. Saul’s knowing now of my intention to join the Diplomatic Service will help allay any suspicions he might have in the future.

‘I’m surprised,’ he says, on the brink of being opinionated. ‘You sure you know what you’re letting yourself in for?’

‘Meaning?’

‘Meaning, why would you want to join the Foreign Office?’

A little piece of spring onion flies out of his mouth.

‘I’ve already told you. Because I’m sick of working for Nik. Because I need a change.’

‘You need a change.’

‘Yes.’

‘So why become a civil servant? That’s not you. Why join the Foreign Office? Fifty-seven old farts pretending that Britain still has a role to play on the world stage. Why would you want to become a part of something that’s so obviously in decline? All you’ll do is stamp passports and attend business delegations. The most fun a diplomat ever has is bailing some British drug smuggler out of prison. You could end up in Albania, for fuck’s sake.’

We are locked into the absurdity of arguing about a problem that does not exist.

‘Or Washington.’

‘In your dreams.’

‘Well, thanks for your support.’

It is still light outside. Saul puts down his fork and twists around. A flicker of eye contact, and then he looks away, the top row of his teeth pressing down on a reddened bottom lip.

‘Look. Whatever. You’d be good at it.’

He doesn’t believe that for a second.

‘You don’t believe that for a second.’

‘No, I do.’ He plays with his unfinished food, looking at me again. ‘Have you thought about what it would be like to live abroad? I mean, is that what you really want?’

For the first time it strikes me that I may have confused the notion of serving the state with a longstanding desire to run away from London, from Kate, and from CEBDO. This makes me feel foolish. I am suddenly drunk on weak American beer.

‘Saul, all I want to do is put something back in. Living abroad or living here, it doesn’t matter. And the Foreign Office is one way of doing that.’

‘Put something back into what?’

‘The country.’

‘What is that? You don’t owe anyone. Who do you owe? The queen? The empire? The Conservative Party?’

‘Now you’re just being glib.’

‘No, I’m not. I’m serious. The only people you owe are your friends and your family. That’s it. Loyalty to the Crown, improving Britain’s image abroad, whatever bullshit they try to feed you, that’s an illusion. I don’t want to be rude, but your idea of putting something back into society is just vanity. You’ve always wanted people to rate you.’

Saul watches carefully for my reaction. What he has just said is actually fairly offensive. I say, ‘I don’t think there’s anything wrong with wanting people to have a good opinion of you. Why not strive to be the best you can? Just because you’ve always been a cynic doesn’t mean that the rest of us can’t go about trying to improve things.’

‘Improve things?’ He looks astonished. Neither of us is in the least bit angry.

‘Yes. Improve things.’

‘That’s not you, Alec. You’re not a charity worker.’

‘Don’t you think we’ve been spoiled as a generation? Don’t you think we’ve grown used to the idea of take, take, take?’

‘Not really. I work hard for a living. I don’t go around feeling guilty about that.’

I want to get this theme going, not least because I don’t in all honesty know exactly how I feel about it.

‘Well, I really believe we have,’ I say, taking out a cigarette, offering one to Saul. ‘And that’s not because of vanity or guilt or delusion.’

‘Believe what?’

‘That because none of us have had to struggle or fight for things in our generation we’ve become incredibly indolent and selfish.’

‘Where’s this coming from? I’ve never heard you talk like this in your life. What happened, did you see some documentary about the First World War and feel guilty that you didn’t do more to suppress the Hun?’

‘Saul…’

‘Is that it? Do you think we should start a war with someone, prune the vine a bit, just to make you feel better about living in a free country?’

‘Come on. You know I don’t think that.’

‘So–what? Is it morality that makes you want to join the Foreign Office?’

‘Look. I don’t necessarily think that I’m going to be able to change anything in particular. I just want to do something that feels…significant.’

‘What do you mean “significant”?’

Despite the fact that our conversation has been premised on a lie, there are nevertheless issues emerging here about which I feel strongly. I stand up and walk around, as if being upright will lend some shape to my words.

‘You know–something worthwhile, something meaningful, something constructive. I’m sick of just surviving, of all the money I earn being plowed back into rent and bills and taxes. It’s okay for you. You don’t have to pay anything on this place. At least you’ve met your landlord.’

‘You’ve never met your landlord?’

‘No.’ I am gesticulating like a TV preacher. ‘Every month I write a cheque for four hundred and eighty quid to a Mr J. Sarkar–I don’t even know his first name. He owns an entire block in Uxbridge Road: flats, shops, taxi ranks, you name it. It’s not like he needs the money. Every penny I earn seems to go toward making sure that somebody else is more comfortable than I am.’

Saul extinguishes his cigarette in a pile of cold noodles. He looks suddenly awkward. Money talk always brings that out in him. Rich guilt.