По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

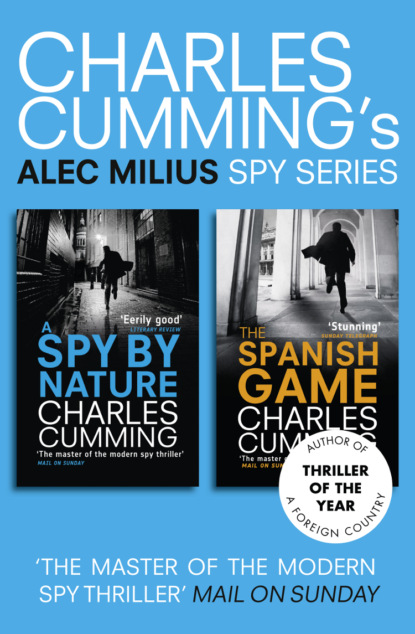

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Not me. Mr Lucas told me in my previous interview that officers are allowed to tell their parents.’

‘Yes.’

‘But as far as friends are concerned…’

‘Of course not.’

‘That’s what I’d come to understand.’

Both of us nod simultaneously. Suddenly, however, for no better reason than that I want to appear solid and reliable, I do something quite unexpected. It is unplanned and dumb. A needless lie to Liddiard that could prove costly.

‘It’s just that I have a girlfriend.’

‘I see. And have you told her about us?’

‘No. She knows that I’m here today, but she thinks I’m applying for the Diplomatic Service.’

‘Is this a serious relationship?’

‘Yes. We’ve been together for almost five years. It’s very probable that we’ll get married. So she should know about this, to see if she’s comfortable with it.’

Liddiard touches his tie again.

‘Of course,’ he says. ‘What is the girl’s name?’

‘Kate. Kate Allardyce.’

Liddiard writes down Kate’s name in his notes. Why am I doing this? They won’t care that I am about to get married. They won’t think any more of me for being able to sustain a long-term relationship. If anything, they would prefer me to be alone.

He asks when she was born.

‘December twenty-eighth, 1971.’

‘Where?’

‘Argentina.’

A tiny crease saunters across his forehead.

‘And what is her current address?’

I had no idea that he would ask so much about her. I give the address where we used to live together.

‘Will you want to interview her? Is that why you want all this information?’

‘No, no,’ he says quickly. ‘It’s purely for vetting purposes. There shouldn’t be a problem. But I must ask you to refrain from discussing your candidature with her until after the Sisby examinations.’

‘Of course.’

Then, as a savoured afterthought, he adds, ‘Sometimes wives can make a substantial contribution to the work of an SIS officer.’

FIVE

Day One/Morning

It’s 6:00 A.M. on Wednesday, August 9. There are two and a half hours until Sisby.

I have laid out a grey flannel suit on my bed and checked it for stains. Inside the jacket there’s a powder-blue shirt at which I throw ties, hoping for a match. Yellow with faint white dots. Pistachio green shot through with blue. A busy paisley, a sober navy one-tone. Christ, I have awful ties. Outside, the weather is overcast and bloodless. A good day to be indoors.

After a bath and a stinging shave I settle down in the sitting room with a cup of coffee and some back issues of The Economist, absorbing its opinions, making them mine. According to the Sisby literature given to me by Liddiard at the end of our interview in July, ‘all SIS candidates will be expected to demonstrate an interest in current affairs and a level of expertise in at least three or four specialist subjects.’ That’s all I can prepare for.

I am halfway through a profile of Gerry Adams when the faint moans of my neighbours’ early-morning lovemaking start to seep through the floor. In time there is a faint groan, what sounds like a cough, then the thud of wood on wall. I have never been able to decide whether she is faking it. Saul was over here once when they started up and I asked his opinion. He listened for a while, ear close to the floor, and made the solid point that you can only hear her and not him, an imbalance that suggests female overcompensation. ‘I think she wants to enjoy it,’ he said, thoughtfully, ‘but something is preventing that.’

I put the dishwasher on to smother the noise, but even above the throb and rumble I can still hear her tight, sobbing emissions of lust. Gradually, too rhythmically, she builds to a moan-filled climax. Then I am left in the silence with my mounting anxiety.

Time is passing. It frustrates me that I can do so little to prepare for the next two days. The Sisby programme is a test of wits, of quick thinking and mental panache. You can’t prepare for it, like an exam. It’s survival of the fittest.

Grab your jacket and go.

The Sisby examination centre is at the north end of Whitehall. This is the part of town they put in movies as an establishing shot to let audiences in South Dakota know that the action has moved to London: a wide-angle view of Nelson’s Column, with a couple of double-decker buses and taxis queuing up outside the broad, serious flank of the National Gallery. Then cut to Harrison Ford in his suite at The Grosvenor.

The building is a great slab of nineteenth-century brown brick. People are already starting to go inside. There is a balding man in a grey uniform behind a reception desk enjoying a brief flirtation with power. He looks shopworn, overweight, and inexplicably pleased with himself. One by one, Sisby candidates shuffle past him, their names ticked off on a list. He looks nobody in the eye.

‘Yes?’ he says to me impatiently, as if I were trying to gatecrash a party.

‘I’m here for the Selection Board.’

‘Name?’

‘Alec Milius.’

He consults the list, ticks me off, gives me a flat plastic security tag.

‘Third floor.’

Ahead of me, loitering in front of a lift, are five other candidates. Very few of them will be SIS. These are the prospective future employees of the Ministry of Agriculture, Social Security, Trade and Industry, Health. The men and women who will be responsible for policy decisions in the governments of the new millennium. They all look impossibly young.

To their left a staircase twists away in a steep spiral and I begin climbing it, unwilling to wait for the lift. The stairwell, like the rest of the building, is drab and unremarkable, with a provincial university aesthetic that would have been considered modern in the mid-1960s. The third-floor landing is covered in brown linoleum. Nicotine-yellow paint clings to the walls. My name, and those of four others, have been typed on a sheet of paper that is stuck up on a pockmarked notice board.

COMMON ROOM B3: CSSB (SPECIAL)

ANN BUTLER

MATTHEW FREARS

ELAINE HAYES

ALEC MILIUS