По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

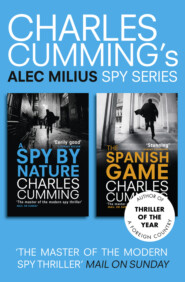

The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

At my regular breakfast café on Calle de Ventura Rodríguez I eat a croissant, with a copy of The Times for company. The Kuwaiti desert is gradually filling with troops and tanks and the prospects for war look bleak: a long drawn-out campaign, and months to take Baghdad. Beside me at the bar a construction worker has ordered a balloon of Pacharán, iced Navarran liqueur, at 8 a.m. I content myself with an orange juice with just a splash of vodka and head outside to the car.

For

250 per month I keep the Audi on the second floor of an underground car park beneath Plaza de España, the vast square at the western end of Gran Vía dominated by a monument to Cervantes. It has been some time since I was last down here and a thin film of dust has formed on the bonnet and across the roof. I lift the spare wheel out of the boot, conceal the bag of money in the moulded recess, remove several CDs from my suitcase for the journey ahead and lay two suits flat along the back seat. A woman passes within ten feet of the car but walks by without so much as a glance. Then it’s just a question of finding the ticket and driving out into rush-hour Madrid. Cars have double-parked along the length of Calle de Ferraz, reducing a three-lane street to traffic that can only bump along in single file. The aggression of horns at this hour of the morning is jarring and I regret not having left an hour earlier. It takes twenty minutes to reach Moncloa and a further ten until we are at last loose on the motorway, bunched traffic moving clockwise on the inner orbital, heading north for Burgos and the Ni. Low clouds have settled on the flat outer plains of Madrid, industrial plants and office blocks broken up by thin, dew-rich mists, but otherwise there is little to look at but endless furniture superstores, German technology companies and blinking roadside brothels. Living in the centre of Madrid, I forget the extent to which the city sprawls out this far, blocks of flats deposited on the featureless plain, built with no greater purpose than proximity to the capital. These could be the outskirts of any major city in the American Midwest. It does not feel like Spain.

The driving, on the other hand, is as Spanish as flamenco and jamón. Cars whipping past at over 160 kph, sliding lane to lane oblivious of sense or reason. It is my habit to copy them, if only because the alternative is a snail-slow crawl in the slipstream of an ageing lorry. Thus I take the Audi well beyond the speed limit, sit on the bumper of the car in front, wait for it to pull to one side, and then surge off into the distance. Traffic police are not a problem. The Guardia Civil tend not to patrol in the long stretches between major towns and one glimpse of my (counterfeit) German driving licence, accompanied by an inability to communicate in Spanish, is usually enough to encourage them to wave me on.

As the weather closes in, however, I am forced to slow down. What had seemed at first like the beginning of a decent, sunny day becomes fogbound and wet, hard rain falling in patches and glistening the road. At this rate it will be four or five hours before I cross the border into the Basque country. A preliminary meeting scheduled in the capital, Vitoria, for one o’clock may have to be postponed or even cancelled. Climbing into the Sierras, I get stuck behind two articulated lorries driving parallel in a macho overtake, and decide to pull over for a coffee rather than sit in the funk of their exhaust. Thankfully, the rain has stopped and the traffic thinned out by the time I rejoin the road, and just after eleven I am passing Burgos. This is where the landscape really comes into its own: rolling, patched fields of green and brown and the distant Cantabrian mountains smashed by a biblical sunlight. At the side of the road, little patches of undecided snow are gradually melting as winter draws to an end. To be away from Madrid, from the pressure and anxiety of Saul, is suddenly liberating.

When the road signs begin to change I know that we have crossed the border. Every town is announced in translation: Vitoria/Gasteiz; San Sebastián/Donostia; Arrasete/Mondragón: government concessions to the demands of Basque nationalism. This is not País Vasco; this is Euskal Herria. Spain is divided into a number of regions with far greater political and social autonomy than, say, devolved Scotland. Under the terms of the constitution hammered out in the aftermath of Franco’s death, the Basques–and the Catalans–were granted the right to form their own regional governments with a president, legislature and supreme court. Everything from housing to agriculture, from education to social security, is organized at a local level. The Basques levy their own taxes, run their own health service–the best in Spain–and even operate an independent police force. As Julian exclaimed over lunch, ‘What more do they fucking want? Explain that in your magnum opus.’

The ‘magnum opus’, as he put it, will probably run to several thousand words, a blend of conjecture, facts and business jargon designed to impress Endiom’s investors and provide a broad overview of the political-financial consequences of investing in the Basque region. ‘Still,’ Julian disclosed, polishing off his second glass of cognac, ‘the idea is to encourage our clients into parting with the readies, yes? No sense in putting them off. No sense at all.’

So, what more do they want? I stop in Vitoria, late for the first of many meetings, and come no closer to an answer. Two hours of employment law and social security benefits with a bespectacled union representative struggling to rein in a bad case of dandruff. It takes twenty-five minutes to find his office and another fifteen for the two of us to walk the damp city streets in search of an eventually mediocre restaurant serving thin soup and stodgy beans. I begin to regret coming. But this is only my second visit to the Basque country and I had forgotten the striking transformation in the landscape as you drive northeast towards the sea, the flat plains of Castilla suddenly soaring into magnificent, bulbous mountains dense with trees and lush grass, the motorway winding frantically along narrow valley floors. This is another country. At half past four I have reached the outskirts of San Sebastián, rain starting to fall and obscuring the hillsides in mist. Every now and again the silhouette of a typical casería, low alpine houses with obtuse angular roofs, will punch through the fog, but otherwise little is visible from the road. So nothing prepares me for the beauty of the city itself, for the long graceful stretch of the Concha, the grandeur of the bridges spanning the Urumea river and the elegance of the broad city streets. Julian’s secretary, Natalia, has booked me into the Londres y de Inglaterra, perhaps the best hotel in town, situated on the seafront looking out over a wide promenade dotted with benches and old men wearing black Basque berets. The promenade is lined by a white iron balustrade and there is no traffic in sight. It would not seem strange for a woman carrying a parasol to pass on the arm of a Spanish gentleman, nor for a child bowling a hoop along the seafront to scurry past in a pair of salmon-pink culottes. I seem to have emerged into a time warp of the fin-de-siècle bourgeoisie, as if the heart of San Sebastián has not changed in over a hundred years, and all of the grim political sparring of the Franco years and beyond has been a myth now happily exploded.

Natalia has reserved a room with a view looking out into the centre of the bay, a perfect natural harbour crowned by a bowl of pristine sand which sweeps in a precise crescent along its southern edge. Even in the cold of February, brave swimmers are inching gingerly out to sea, shivering in the soft breakers rolling in off the Bay of Biscay. I take a shower, write down some notes from the meeting at lunch and fall asleep in front of CNN.

I am woken just after seven by the shrill of the telephone, a call from Julian in Madrid.

‘Forgot something,’ he says, as if we had been in mid-conversation. ‘Meant to say at lunch yesterday, completely slipped my mind.’

‘And what’s that?’

‘I think you should look up an old acquaintance of mine, useful for the magnum opus. Chap by the name of Mikel Arenaza. Belongs to Batasuna. Or, at least he did.’

‘To Batasuna? Since when did you start making friends with them?’

Herri Batasuna was the political wing of ETA until the party was banned in the late summer of 2002. For an unreconstructed blue-blood like Julian Church to have an ‘acquaintance’ within its ranks seems as unlikely to me as Saul getting a Christmas card from Gerry Adams.

‘I’m a man of mystery,’ Julian says, as if that explains it. He is tapping something on his desk. ‘Truth is, Mikel approached us a few years back with an investment proposal we were obliged to turn down on ethical grounds. Hugely entertaining individual, however, and somebody you should definitely look up. Bon viveur, ladies’ man, speaks immaculate English. You’ll like him.’

Why does Julian think that I would like a ladies’ man? Because of suspicions he has about Sofía? As a consequence of Saul’s interventions over the weekend I am trying to suppress my wilder flights of paranoia, but there is something I don’t like about this. It feels like a set-up.

‘So you stayed friends? You and this Mikel? A representative of a terrorist organization in cahoots with the boss of a British private bank?’

‘Well I wouldn’t say “cahoots”, Alec. Not “cahoots”. Look, if it makes you uneasy, God knows I understand…’

‘No, it doesn’t make me uneasy. I’m just surprised, that’s all.’

‘Well then, fine, why not give him a call? Natalia will email you his details. No sense in spending all of your time up there lunching with lawyers and car salesmen. You might as well enjoy yourself.’

NINE

Arenaza

Mikel Arenaza, politician and friend of terror, is a lively, engaging man–I could tell as much by his manner on the phone–but the full extent of his ebullient self-confidence becomes apparent only upon meeting him. We arrange to have a drink in the old town of San Sebastián, not in an herrika taverna–the type of down-at-heel pub favoured by the radical, left-wing nationalist abertzale– but in an upmarket bar where waves of tapas and uncooked mushrooms and peppers cover every conceivable surface, two barmen and a young female chef working frantically in sight of the customers. It is my final evening in the city, after three solid days of meetings, and Arenaza arrives late, picking me out of the crowd within an instant of walking through the door, at least six feet of heavy good looks pulling off a charming smile beneath an unbrushed explosion of wild black hair. The fact that he is wearing a suit surprises me; the average Batasuna councillor might view that as a sop to Madrid. On television, in the Spanish parliament for example, they are often to be seen dressed as if for a football match, in sartorial defiance of the state. Nevertheless, a single studded ear-ring in his right lobe goes some way towards conveying the sense of a subversive personality.

‘It is Alec, yes?’

A big handshake, eyes that gleam on contact. The ladies’ man.

‘That’s right. And you must be Mikel.’

‘Yes indeed I am. Indeed.’

He moves forcefully, all muscle-massed shoulders and bulky arms, wit and cunning coexistent in the arrangement of his face. Was it my imagination, or did time stand still for a split second, the bar falling quiet as he came in? He is known here, a public figure. Arenaza nods without words at the older of the two barmen and a caña doble appears with the speed of a magic trick. His eyes are inquisitive, sizing me up, a persistent grin at one edge of his mouth.

‘You’ve found a table. This is not always easy here, it’s a triumph. So we can talk. We can get to know each other.’

His English is heavily accented and delivered with great confidence and fluidity. I do not bother to ask whether he would rather speak in Spanish; in the absence of Basque, English will be his preferred second language.

‘And you work for Julian?’ The question appears to amuse him. ‘He is the typical English banker, no? Eton school and Oxford?’

‘I guess so. That’s the stereotype.’ Only Julian went to Winchester, not Eton. ‘How do you know him?’

There is a fractional pause. ‘Well, we tried to do some business together a long time ago but it did not come off. However, it was an interesting time and now whenever I go to Madrid I always try to have a dinner with him. He has become my friend. And Sofía, of course, such a beautiful woman. The British always taking our best wives.’ A laugh here, of Falstaffian dimensions. Arenaza, who must be about Julian’s age, has sat down with his back to the room on a low stool which does nothing to diminish his sheer physical impact. He offers his glass in a toast. ‘To Mr and Mrs Church, and to bringing us together.’ Clink. ‘What is it that you think I can do for you?’

He may be in a hurry; the man-about-town with fifty better things to do. It occurs to me that whatever information he might usefully impart for my report will have to be extracted within the next half-hour. It is the challenge of spies to win the confidence of a stranger and I would like to know more about Mikel Arenaza, yet charisma of his sort usually denotes a distracted and restless personality. Time is of the essence.

‘What would be most useful for Endiom to know is your view on the question of separatism. What has become of your party in the wake of the ban? Do you think the Basque people would vote for independence in a referendum? That kind of thing.’

Arenaza bounces his eyebrows and puffs out his cheeks in a well-rehearsed attempt at looking taken aback. I note that he is wearing a very strong aftershave.

‘Well, it’s not unusual to meet an Englishman who arrives straight to the point. I assume you are English, no?’

I take a chance here, going with a pre-arranged plan based on Arenaza’s ideological convictions.

‘Actually my father was Lithuanian and my mother is Irish.’ Two sets of suitably oppressed peoples for a Basque to mull over. ‘They settled in England when my father found work.’

‘Really?’ He looks gratifyingly intrigued. ‘Your mother is from Ireland?’

‘That’s right. County Wicklow. A farm near Bray. Do you know the area at all?’

Mum is actually Cornish, born and bred, but ETA and the IRA have always had very close ties, shared networks, collective goals. About a year ago a general in the Spanish army was killed by a bicycle bomb, a technique ETA were believed to have acquired from the Irish.

‘Only Dublin,’ Arenaza replies, offering me a cigarette which I decline. It’s a South American brand–Belmont–which I have seen only once before. He lights one and smiles through the initial smoke. ‘I have been to several conferences there, also once to Belfast.’

‘And you’re just back from South America?’

He looks taken aback.

‘From Bogotá, yes. How did you know this?’

‘Your cigarettes. You’re smoking a local brand.’

‘Well, well.’ He mutters something to himself in Basque. ‘You’re a very observant person, Mr Milius. Julian makes a good decision in hiring you, I think.’

It is a politician’s flattery, but welcome none the less. I say, ‘Eskerrik asko’–the Basque for ‘thank you’–and lead him back into the conversation.