По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

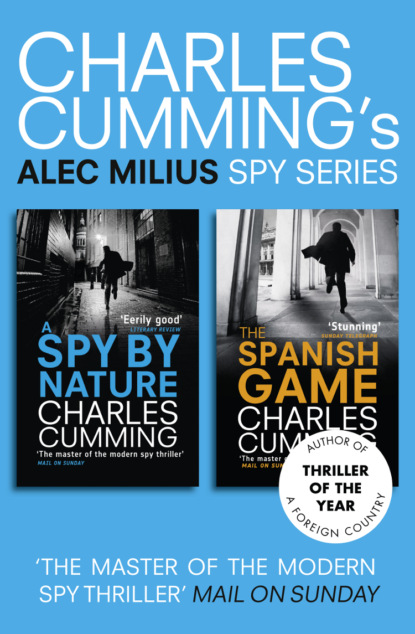

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Keith coughs.

‘In just over ten minutes you’ll begin the group exercise,’ he says, leaning to pick up a small pile of papers from the top right corner of his desk. ‘This involves a thirty-minute discussion among the five of you on a specific problem described in detail in this document.’

He flaps one of the sheets of paper beside his ear and then begins distributing them, one to each of us.

‘You have ten minutes to read the document. Try to absorb as much of it as possible. The board will explain how the assessment works once you have gone into the second examination area. Any questions?’

Nobody says a word.

‘Right, then. Can I suggest that you begin?’

This is what it says:

A nuclear reprocessing plant on the Normandy coast, built jointly in 1978 by Britain, Holland, and France, is allegedly leaking minute amounts of radiation into a stretch of the English Channel used by both French and British fishermen. American importers of shellfish from the region have run tests revealing the presence of significant levels of radiation in their consignments of oysters, mussels, and prawns. The Americans have therefore announced their intention to stop importing fish and shellfish from all European waters, effective immediately.

The document–which has been written from the British perspective by a fictional civil servant in the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food–suggests that the American claims are nebulous. Their own tests, carried out in conjunction with the French authorities, have shown only trace levels of radiation in that section of the English Channel, and nothing in the shellfish from the area that might be construed as dangerous. The civil servant suspects an ulterior motive on the part of the Americans, who have objected in the past to what they perceive as unfair fishing quotas in European waters. They have asked for improved access to European fishing grounds, and for the French plant to be shut down until a full safety check has been carried out.

The document suggests that the British and French ministries should present a united, pan-European resistance to face off the American demands. But there are problems. An American car company is one step away from signing a contract with the German government to build a factory near Berlin that would bring over three thousand jobs to an economically deprived area. The Germans are unlikely to do anything at this stage to upset this agreement. Ditto the Danes, who have an ongoing row with the French over a recent trade agreement. The Spanish, who would suffer more than anyone under any prolonged American export ban, will side firmly with the British and French, though their position is weakened by the fact that the peseta is being propped up by the U.S. dollar.

It’s a fanciful scenario, but this is what we are required to talk about.

Keith has given each of us a sheet of blank paper on which to scribble notes, but I write as little as possible. Eye contact will be important in front of the examiners: I must appear confident and sure of my brief. To be constantly buried in pages of notes will look inefficient.

Ten minutes pass quickly. Keith asks us to gather up our things and accompany him to another section of the building. It takes about four minutes to get there.

Two men and an elderly lady are lined up behind a long rectangular desk, like judges in a bad production of The Crucible. They have files, notepads, full glasses of water, and a large chrome stopwatch in front of them. The classroom is small and cheaply furnished, with just the one window. Somehow I expected a grander setup: varnished floors, an antique table, old men in suits peering at us over half-moon spectacles. A stranger might walk in here and be offered no hint that the three people inside are part of the most secret government department of them all. And that, of course, is as it should be. The last thing we are supposed to do is draw attention to ourselves.

‘Good morning,’ says the older of the two men. ‘If you’d all like to take a seat, we’ll make a start.’

From his accent, he is unmistakably English, yet his suntan is so pronounced that he might almost be Indian. He looks well into his fifties.

There is a table with five chairs positioned around it no more than two feet away from the examiners. We move toward it and are suddenly very polite to one another. Shall I go here? Is that all right? After you. Ann, I think, overdoes it, actually holding Elaine’s chair for her. I find myself in the seat farthest from the door, flushed with shirt sweat, trying to remember everything I have read while at the same time appearing relaxed and self-assured. An age passes until we are all comfortably seated. Then the man speaks again.

‘First off, allow us to introduce ourselves. My name is Gerald Pyman. I am a recently retired SIS officer. I’ll be chairing the Selection Board for the next two days.’

Pyman’s eyes are like black holes, as if they have seen so much that is abject and contemptible in human nature that they have simply withdrawn into their sockets. He wears a tie, a smart one, but no jacket in the heat.

‘To my left is Dr Hilary Stevenson.’

‘Good morning,’ she says, taking up his cue. ‘I’m the appointed psychologist to the board. I’m here to evaluate your contributions to the group exercises and–as you will all have seen from your timetables–I will also be conducting an interview with each of you over the course of the next two days.’

She has a kind, refined way of speaking, the trusting softness of a grandmother. The room is absolutely still as she speaks. Each of us has adopted a relaxed but businesslike body language: arms on laps or resting on the table in front of us. Ogilvy is the exception. His arms are folded tight against his chest. He seems to realize this and lets them drop to his sides. It is the turn of the man on Pyman’s right to speak. He is a generation younger, overweight by about forty pounds, with a pale, rotund face that is tired and paunchy.

‘And I’m Martin Rouse, a serving SIS officer working out of our embassy in Washington.’

Washington? Why do we need intelligence operations in Washington?

‘Can I just emphasize that you are not in competition. There’s nothing at all to be gained from scoring points off one another.’

Rouse has a faint Manchester accent, diluted by a life lived overseas.

‘Now,’ he says, ‘we’ll just go around the table and allow you to introduce yourselves to us and to each other. Beginning with Mr Milius.’

I experience the sensation of breathing in both directions at once, inhalation and exhalation cancelling each other out. Every face in the room shifts minutely and settles on mine.

I look up and for some reason fix Elaine in the eye as I say, ‘My name is Alec Milius. I am a marketing consultant.’

Then I slide my gaze away to the right, taking in Stevenson, Rouse, and Pyman, a sentence for each of them.

‘I work in London for the Central European Business Development Organization. I’m a graduate of the London School of Economics. I’m twenty-four.’

‘Thank you,’ says Rouse. ‘Miss Butler.’

Ann dives right in, no trace of nerves, and introduces herself, quickly followed by the Hobbit. Then it’s Ogilvy’s turn. He visibly shifts himself up a gear and, in a clear, steady voice, announces himself as the surefire candidate.

‘Good morning.’

Eye contact to us, not to the examiners. Nice touch. He stares me right down without a flinch and then turns to face Elaine. She remains unmoved.

‘I’m Sam Ogilvy. I work for Rothmans Tobacco in Saudi Arabia.’

This information knocks me sideways. Ogilvy can’t be much older than I am, yet he’s already working for a major multinational corporation in the Middle East. He must be earning thirty or forty grand a year with a full expense account and company car. I’m on less than fifteen thousand and live in Shepherd’s Bush.

‘I graduated from Cambridge in 1992 with a first in economics and history.’

Bastard.

‘Thank you, Mr Ogilvy,’ says Rouse, planting a full stop on his pad as he looks up at Elaine and smiles for the first time. He doesn’t need to say anything to her. He merely nods, and she begins.

‘Good morning. I’m Elaine Hayes. I’m already employed by the Foreign Office, working out of London. I’m thirty-two, and I can’t remember when I graduated from university it was such a long time ago.’

Both Pyman and Rouse laugh at this and we follow their cue, mustering strained chuckles. The room briefly sounds like a theatre in which only half the audience has properly understood a joke. It intrigues me that Elaine is already employed by the Foreign Office. If she was looking to join SIS, surely they would promote her internally without the bother of going through Sisby?

‘We’d like to proceed now with the group exercise,’ Pyman says, interrupting this thought. ‘The discussion is unchaired, that is to say you are free to make a contribution whenever you choose to do so. It is scheduled to conclude after thirty minutes, at which time you must all have agreed upon a course of action. If you find yourselves in agreement before the thirty minutes are up, we shall call a stop then. I must emphasize the importance of making your views known. There is no point in holding back. We cannot assess your minds if you will not show them to us. So do participate. There’s a stopwatch here. Miss Hayes, if you’d like to start it up and set it on the desk where everyone can see it.’

Elaine is closest to Rouse, who takes the stopwatch from Pyman and hands it to her with his right arm outstretched. She takes it from him and sets it down on the table, positioning the face in such a way that we can all see it. Then, with her thumb, she pushes the bulbous steel knob at the top of the stopwatch, starting us off.

It has a tick like chattering teeth.

‘Can I just say to begin with that I think it’s very important that we maintain a tight alliance with the French, though the problem is of their making. Initially, at least.’

Ann, God bless her, has had the balls to kick things off, although her opening statement has a forced self-confidence about it that betrays an underlying insecurity. Like a pacesetter in a middle-distance track event, she’ll lead for a while but soon tire and fall away.

‘Do you agree?’ she says, to no one in particular, and her question has a terrible artificiality about it. Ann’s words hang there unanswered for a short time, until the Hobbit chips in with a remark that is entirely unrelated to what she has said.

‘We have to consider how economically important fish exports are to the Americans,’ he says, touching his right cheekbone with a chubby index finger. ‘Do they amount to much?’

‘I agree.’