По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

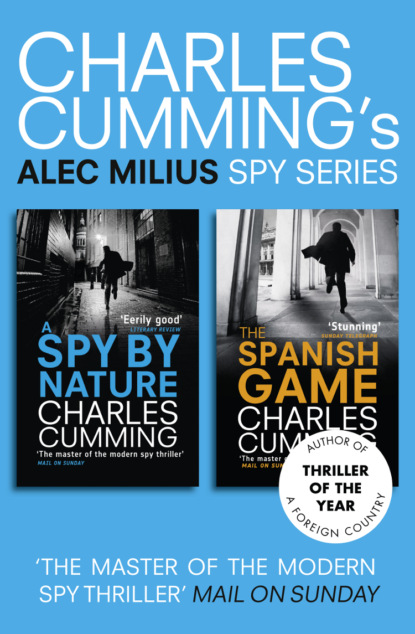

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Of course,’ says Ogilvy, cutting her off before she has a chance to tell him how unworkable a trade embargo with the United States would be, ‘I actually don’t think that we’ll have to go as far as reciprocating their ban with one of our own.’

He wants to show Rouse and Pyman that he’s seen all the angles.

‘The key to this, as I’ve said, is the Germans. If we can get them on our side, and as long as any problem with the reprocessing plant can be addressed, I can’t foresee the Americans continuing with their demands. It’s important that we be seen to stand up to them.’

It’s time to steal some ideas from Ogilvy, before he runs away with it.

‘The sticking point is the automobile manufacturer. We have to make sure that that contract is secured and goes ahead. At the same time, we might offer the Germans a sweetener.’

‘What kind of a sweetener?’ Elaine asks. She lingers on sweetener as if it is the most absurd word she has ever heard.

‘Sell them something. At a bargain price. Or we could buy more of their exports.’

This sounds meek and ill-informed. It is clear that I have not thought it through. But Ogilvy bails me out, saying yes with a degree of enthusiasm that I had not anticipated. Ironically, this leads to a bad mistake. He says, ‘We could offer to buy up deutsch marks, to push up their value briefly against the pound.’

This is ludicrous, and Elaine tells him so.

‘You try it. You’d have to be owed some pretty big favours at the Exchequer to get something like that done.’

She delivers this in a tone of weary experience and for a moment Ogilvy is stumped. His square jaw tremors with humiliation, and it gives me a small buzz of pleasure to watch him ride it out. It’s important that I don’t let this opportunity slip. Shut him down.

‘I have to agree with Elaine, Sam. We mustn’t pass the buck to another department. It’s difficult, without knowing more about our other negotiations with the Germans, to determine how exactly we might go about persuading them to side with us. It may not even be necessary, for two reasons. The first has already been made clear. The French plant may in fact be safe and the Americans may be acting illegally. If that’s the case, we’re in the clear. But if it does prove necessary to get the Germans onside, we could try another tactic.’

‘Yes, I–‘Ann tries to grab the floor, but I’m not about to be interrupted.

‘If I could just finish. Thank you. If we succeed in convincing a majority of other European states to form a united front against the Americans, the Germans will not relish being isolated. While they may not want to be seen to be taking issue with the United States, at the same time they won’t want to be seen by their European partners to be forming an unholy alliance with America. We can, in effect, shut them up.’

‘We shouldn’t underestimate the Germans or their influence,’ the Hobbit mumbles. ‘Nobody here wants to acknowledge the truth of this situation, which is that the Germans are the dominant economic force in European politics. They are, in effect, our masters.’

This annoys me.

‘Well, if that’s what they’re teaching you on your European affairs course at Warwick, I’m not signing up.’

Elaine, Pyman, and Rouse emit snorty laughs. I’m winning this, I’m coming through. The Hobbit’s cheeks rouge nicely. He can’t think of a comeback, so I carry on.

‘This notion of the Germans as the European master race is contrived. Their economy will slow in the next few years, unemployment is chronic since unification, and Kohl’s days are numbered.’

I read this in The Economist.

‘Let’s not get off the point.’ Ogilvy wants back in. ‘Let’s talk about how to get the Spaniards and the Danes onboard.’

Suddenly Ann sneezes, a great lashing a-choo that she only half covers with her hand. In stereo, Ogilvy and I say, ‘Bless you,’ to which he adds, ‘Are you okay?’ Ann, not one to be patronized, lets her guard drop and says, ‘Yeah,’ with sullen indifference. Her voice, with its sour accent, sounds impatient and spoiled. In this brief moment, we can all see her for what she really is: a tough nut of steely ambition, looking for a one-way ticket to London and a better life. In the wake of it, Ogilvy glides away, talking with great efficiency about how to get the Spaniards and Danes ‘on board.’ As time ticks away, the stopwatch edging toward our thirty-minute limit, he is left more or less on his own, with occasional interjections from the Hobbit, whose knowledge of European Union bylaws is as extensive as it is tedious. He must be the star pupil at Warwick. Ann, for the most part, turns in on herself and merely disagrees for the sake of disagreeing. Elaine barely speaks. From my point of view, I feel that I have done enough to please the examiners, both by what I have said and by my personal conduct, which has been forthright but respectful of the other candidates. I also feel that Ogilvy and the Hobbit are flogging a dead horse. Most of the points that were there to be made have been made saliently some time ago. Nevertheless, it will look good if I try to wrap things up.

‘If I could just interrupt you there, Sam, because we’re running out of time, and I think we should try to reach some sort of conclusion.’

‘Absolutely.’

He gives me the floor. Don’t fuck it up.

‘I think we’ve covered most of the angles on this problem. Judging from the last ten minutes or so, we’re mostly agreed on a course of action.’

‘Which is?’ says Ann, coldly.

‘That we need to–as you pointed out right at the start–present a united front to the Americans. We must conduct conclusive tests on the French plant. If needs be, we should bargain with the Germans to get them on our side.’

‘We never said how we were going to do that.’ The manner in which Elaine says this, with just under a minute to go, implies that this is largely my responsibility.

‘No, we didn’t. But that’s not something that should worry us. I think the Germans would be unlikely to do anything that would undermine the EU.’

‘And what do we do about the American export ban?’ the Hobbit asks, looking in my direction as he tips forward on his chair. It was a mistake to take this on.

‘Well, there’s very little we can do…’

‘I don’t agree,’ says Ann, cutting me off short so that my incomplete sentence sounds weak and defeatist.

‘Me too,’ says Ogilvy, but he too is interrupted.

‘I’m afraid that your thirty minutes is up.’

Rouse has tapped his pen twice–tap tap–on the hard surface of the examiners’ table. We all turn to face him.

‘Thank you all very much. If you’d like to gather up your things and make your way back to the common room, where Mr Heywood is waiting for you.’

I think we all share a sense of disappointment at not managing to conclude the discussion within the allocated time. It will reflect badly on the five of us, although I may score points for trying to tidy things up toward the end. Ogilvy is first up and out of the room, followed by the rest of us in a tight group, waddling out like tired ducks. Elaine is the last to leave, closing the door behind her. She does this with too much force, and it slams shut with a loud clap.

Keith is waiting for us in the common room, idling near the coffee machine. As soon as we are all inside, he instructs us to follow him back down the corridor to begin the first of the written examinations. There is no time to relax, no time to ruminate or grab a drink. They won’t let the pressure off until five o’clock this evening, and then it starts all over again tomorrow.

On the way to the classroom, Elaine and Ann peel away from the group to go to the loo. This flusters Keith. While Ogilvy, the Hobbit, and I are taking our seats in the classroom, he lurks nervously in the corridor, waiting for their return.

The Hobbit, who has taken a seat by the window, grabs this opportunity to tuck into yet another cereal bar. Ogilvy returns to his previous spot at the back of the room. To annoy him I move to the desk nearest his, close in and to the left. For a moment it looks as though he may move, but politeness checks him. He looks across at me and smiles very slowly.

With no sign of Elaine and Ann, Keith trundles back in, head bowed, and starts handing out thick pink booklets, which he leaves facedown on every candidate’s desk. The Hobbit thanks him through the crumbly munch of his mid-morning snack, and Ogilvy begins twirling a pencil in his right hand, rotating it quickly through his fingers like a helicopter blade. It’s a poser’s party trick and it doesn’t come off: the pencil spins out of his hand and clatters onto the lino between our two desks. I make no attempt to retrieve it, so Ogilvy has to bend down uncomfortably to pick it up. As he is doing so, Elaine and Ann bustle in, sharing the cozy mutual smiles and solidarity of women returning from a shared trip to the loo.

‘This section of the Sisby program is known as the Policy Exercise,’ Keith says, beginning his introductory talk before they have had a chance to sit down. He’s on a strict timetable, and he’s sticking to it. ‘It is a two-hour written paper in which you will be asked to analyse a large quantity of complex written material, to identify the main points and issues, and to write a thorough and cogently argued case for one of three possible options.’

I stare at the pink booklet and pray for something other than shellfish.

‘You may start when you are ready. I will let you know when one hour of the examination has passed, and again when there are ten minutes of the exercise remaining.’

A crackle of paper, an intake of breath, the incidental noises of beginning.

Here we go again.

SIX

Day One/Afternoon

After lunch–a ham and cheese sandwich at the National Gallery–we sit in the stifling classroom faced by a phalanx of numerical facility tests divided into three separate sections: Relevant Information, Quantitative Relations, and Numerical Inferences. Each batch of twenty questions lasts exactly twenty-two minutes, after which Keith allows a brief interlude before starting us on the next paper. Each problem, whether number-or word-based, must be solved in a matter of seconds, with no time available for checking the accuracy of the answer. Calculators are forbidden. It is by far the most testing part of Sisby so far, and the mind-thud of intellectual fatigue is overwhelming. I crave water.