По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

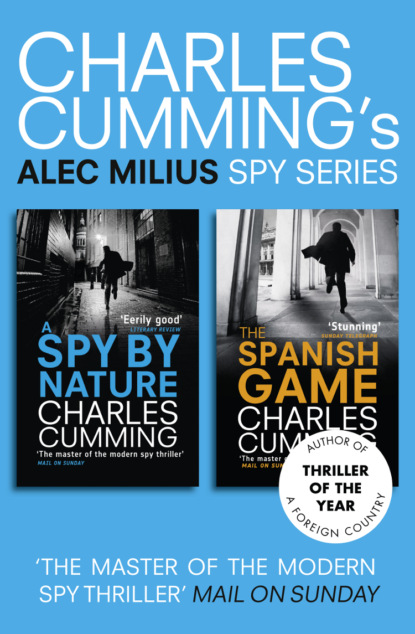

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

We are all of us squeezed by time, clustered in the classroom like caged hens as the heat intensifies. Everything–even the most testing arithmetic calculation–has to be answered more or less on instinct. At one point I have to estimate 43 per cent of 2,345 in under seven seconds. Often my brain will work ahead of itself or lag behind, concentrating on anything but the problem at hand. The tests blur into a soup of numbers, traps of contradictory data, false assumptions, and trick questions. Any apparent simplicity is quickly revealed as an illusion: every word must be examined for what it conceals, every number treated as an elaborate code. My ability to process information gradually wanes. I don’t complete any of the three batches of tests to my satisfaction.

Shortly before four o’clock, Keith asks us with nasal exactitude to stop writing. Ogilvy immediately glances across to gauge how things have gone. He tilts his head to one side, creases his brow, and puffs out his cheeks at me, as if to say, I fucked that up, and I hope you did, too. For a moment I am tempted into intimacy, a powerful urge to reveal to him the extent of my exhaustion, but I cannot allow any display of weakness. Instead, I respond with a self-possessed, almost complacent shrug to suggest that things have gone particularly well. This makes him look away.

A few minutes later, we emerge narrow-eyed into the bright white light of the corridor. Better air out here, cool and clean. The Hobbit and Ann immediately walk away in the direction of the toilets, but Ogilvy lingers outside, looking bloodshot and leathery.

‘Christ,’ he says, pulling on his jacket with an exaggerated swagger. ‘That was tough.’

‘You found it difficult?’ Elaine asks. My impression has been that she does not like him.

‘God, yeah. I couldn’t seem to concentrate. I kept looking at you guys scribbling away. How did it go for you, Alec?’

He smiles at me, like we’re long-term buddies.

‘I don’t go in for postmortems much.’ To Elaine: ‘You got a cigarette?’

She takes out a pack of high-tar Camels.

‘I only have one left. We can share.’

She lights up, crushing the empty pack in her hand. Ogilvy mutters something about giving up smoking, but looks excluded and weary.

‘I need to get some fresh air,’ he says, moving away from us down the hall. ‘I’ll see you later on.’

Elaine exhales through her nostrils, two steady streams of smoke, watching him leave with a critical stare.

‘Have you got anything else today?’ she asks me. ‘An interview or anything?’

I don’t feel like talking. My mind is looped around the penultimate question in the last batch of tests. The answer was closer to 54 than 62, and I circled the wrong box. Damn.

‘I have to meet Rouse. The SIS officer.’

She glances quickly left and right.

‘Careless talk costs lives, Alec,’ she whispers, half smiling. ‘Be careful what you say. The five of us are the only SIS people here today.’

‘How do you know?’

‘It’s obvious,’ she says, offering the cigarette to me. The tip of the filter is damp with her saliva and I worry that when I hand it back she will think the wetness is mine. ‘They only process five candidates a month.’

‘According to who?’

She hesitates.

‘It’s well known. A lot more reach the initial interview stage, but only five get through to Sisby. We’re the lucky ones.’

‘So you work in the Foreign Office already. That’s how you know?’

She nods, glancing again down the corridor. My head has started to throb.

‘Pen pushing,’ she says. ‘I want to step up. Now, no more shoptalk. What time are you scheduled to finish?’

‘Around five.’

Her hair needs washing and she has a tiny spot forming on the right side of her forehead.

‘That’s late,’ she says, sympathetically. ‘I’m done for the day. Back tomorrow at half past eight.’

The cigarette is nearly finished. I had been worried that it would set off a fire alarm.

‘I guess I’ll see you then.’

‘Guess so.’

She is turning to leave when I say, ‘You don’t have anything for a headache, do you? Dehydration.’

‘Sure. Just a moment.’

She reaches into the pocket of her jacket, rustles around for something, and then uncurls her right hand in front of me. There in the palm of her hand is a short strip of plastic containing four aspirin.

‘That’s really kind of you. Thanks.’

She answers with a wide, conspiratorial smile, dwelling on the single word, ‘Pleasure.’

In the bathroom, I turn on the cold tap and allow it to run out for a while. Flattery is implicit in Elaine’s flirtations. She has ignored the others–particularly Ogilvy–but made a conscious effort to befriend me. I puncture the foil on the plastic strip of pills and extract two aspirin, feeling them dry and hard in my fingertips. Drinking water from a cupped hand, I tip back my head and let the pills bump down my throat. My reflection in the mirror is dazed and washed out. Have to get myself together for Rouse.

Behind me, the door on one of the cubicles unbolts. I hadn’t realized there was someone else in the room. I watch in the mirror as Pyman comes out of the cubicle nearest the wall. He looks up and catches my eye, then glances down, registering the strip of pills lying used on the counter. What looks like mild shock passes quickly over his face. I say hello in the calmest, it’s-only-aspirin voice I can muster, but my larynx cracks and the words come out subfalsetto. He says nothing, walking out without a word.

I spit a hoarse ‘fuck’ into the room, yet something body-tired and denying immediately erases what has just occurred. Pyman has seen nothing untoward, nothing that might adversely affect my candidacy. He was simply surprised to see me in here, and in no mood to strike up a conversation. I cannot be the first person at Sisby to get a headache late in the afternoon on the first day. He will have forgotten all about it by the time he goes home.

This conclusion allows me to concentrate on the imminent interview with Rouse, whose office–B14–I begin searching for along the corridors of the third floor. The room is situated in the northwestern corner of the building, with a makeshift nameplate taped crudely to the door: MARTIN ROUSE: AFS NON-QT/CSSB SPECIAL.

I knock confidently. There is a loud, ‘Come in.’

His office smells of bad breath. Rouse is pacing by the window like a troubled general, the tail of a crumpled white shirt creeping out the back of his trousers.

‘Sit down, Mr Milius,’ he says. There is no shaking of hands.

I settle into a hard-backed chair opposite his desk, which has just a few files and a lamp on it, nothing more. A temporary home. The window looks out over St. James’s Park.

‘Everything going okay so far?’

‘Fine, thank you. Yes.’

He has yet to sit down, yet to look at me, still gazing out the window.

‘Candidates always complain about the Numerical Facility tests. You find those difficult?’

It isn’t clear from his tone whether he is being playful or serious.