По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

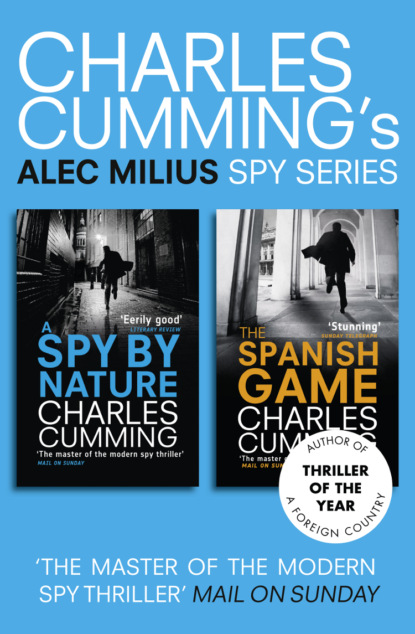

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It’s been a long time since I had to do maths without a calculator. Good exercise for the brain.’

‘Yes,’ he says, murmuring.

It is as if his thoughts are elsewhere. It was not possible during the group exercise to get a look at the shape of the man, the actual physical presence, but I can now do so. His chalky face is entirely without distinguishing characteristics, neither handsome nor ugly, though the cheekbones are swollen with fat. He has the build of a rugby player, but any muscle on his broad shoulders has turned fleshy, pushing out his shirt in unsightly lumps. Why do we persist with the notion of the glamorous spy? Rouse would not look out of place behind the counter of a butcher’s shop. He sits down.

‘I imagine you’ve come well prepared.’

‘In what sense?’

‘You were asked to revise some specialist subjects.’

‘Yes.’

His manner is almost dismissive. He is fiddling with a fountain pen on his desk. Too many thoughts in his head at any one time.

‘And what have you read up on?’

I am starting to feel awkward.

‘The Irish peace process…’

He interrupts before I have a chance to finish.

‘Ah! And what were your conclusions?’

‘About what?’

‘About the Irish peace process,’ he says impatiently. The speed of his voice has quickened considerably.

‘Which aspect of it?’

He plucks a word out of the air.

‘Unionism.’

‘I think there’s a danger that John Major’s government will jeopardize the situation in Ulster by pandering to the Unionist vote in the House of Commons.’

‘You do?’

‘Yes.’

‘And what would you do instead? I don’t see that the prime minister has any alternative. He requires legislation to be passed, motions of no confidence to be quashed. What would you do in his place?’

This quick, abrasive style is what I had expected from Lucas and Liddiard. More of a contest, an absence of civility.

‘It’s a question of priorities.’

‘What do you mean?’

He is coming at me quickly, rapid jabs under pressure, allowing me no time to design my answers.

‘I mean does he value the lives of innocent civilians more than he values the safety of his own job?’

‘That’s a very cynical way of looking at a very complex situation. The prime minister has a responsibility to his party, to his MPs. Why should he allow terrorists to dictate how he does his job?’

‘I don’t accept the premise behind your question. He’s not allowing terrorists to do that. Sinn Fein/IRA have made it clear that they are prepared to come to the negotiating table and yet Major is going to make decommissioning an explicit requirement of that, something he knows will never happen. He’s not interested in peace. He’s simply out to save his own skin.’

‘You don’t think the IRA should hand over its weapons?’

‘Of course I do. In an ideal world. But they never will.’

‘So you would just give in to that? You would be prepared to negotiate with armed terrorist organizations?’

‘If there was a guarantee that those arms would not be used during that negotiating process, yes.’

‘And if they were?’

‘At least then the fault would lie with Sinn Fein. At least then the peace process would have been given a chance.’

Rouse leans back. The skin of his stomach is visible as pink through the thin cotton of his shirt. Here sits a man whose job it is to persuade Americans to betray their country.

‘I take your point.’

This is something of a breakthrough. There is a first smile.

‘What else, then?’

‘I’m sorry, I don’t understand.’

‘What else have you prepared?’

‘Oh.’ I had not known what he meant. ‘I’ve done some research on the Brent Spar oil platform and some work on the Middle East.’

Rouse’s face remains expressionless. I feel a droplet of sweat fall inside my shirt, tracing its way down to my waist. It appears that neither of these subjects interests him. He picks up a clipboard from the desk, turning over three pages until his eyes settle on what he is looking for. All these guys have clipboards.

‘Do you believe what you said about America?’

‘When?’

He looks at his notes, reading off the shorthand, quoting me, “‘The Americans have a very parochial view of Europe. They see us as a small country.’”

He looks up, eyebrows raised. Again it is not clear whether this is something Rouse agrees with, or whether his experience in Washington has proved otherwise. Almost certainly, he will listen to what I have to say and then take up a deliberately contrary position.

‘I believe that there is an insularity to the American mind. They are an inward-looking people.’

‘Based on what evidence?’

His manner has already become more curt.