По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

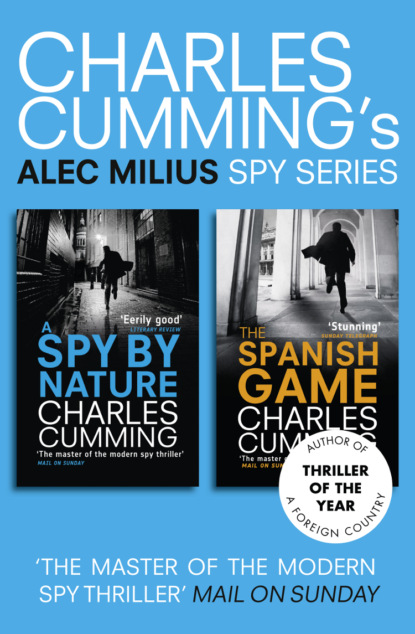

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I can understand that. These matters are never simple.’

‘I can hear myself say certain things to you about my father and then something else inside me will contradict that. Does that make sense? It’s a very confusing situation. What I’m trying to say is that there are no set answers.’

Stevenson makes to say something, but I speak over her.

‘For example, I would like my father to be around now so that we could talk about Sisby and SIS. Mum says that he was like me in a lot of ways. He didn’t keep a lot of friends, he didn’t need a lot of people in his life. So we shared this need, this instinct for privacy. And maybe because of that we might have become good friends. Who knows? We could have confided in one another. But I don’t actively miss him because he’s not here to fulfil that role. Things are no more difficult because he’s not available to offer me guidance and advice. It’s more a feeling that I’ll never see his face again. Sometimes it’s that simple.’

Stevenson’s tender eyes are sunk in rolls of skin.

‘How do you think he would have felt about you becoming an SIS officer?’

‘I think he would have been very proud. Perhaps even a little envious.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘It’s every young man’s dream, isn’t it, to join MI6, to serve his country. Dad wouldn’t have thought ideas like that were out-of-date, and neither do I. And I think he would have been good at the job. He was smart, concealed, he could keep a secret. In fact, sometimes I feel like I’m doing this for him, in his memory. That’s why it’s so important to me. I want to show him that I can be a success. I want to make him proud of me.’

Stevenson looks perplexed and I feel that I may have gone too far.

‘Yes,’ she says, writing something down. ‘And Kate? How does she feel?’

This may be a test: they will want to know if I have broken the Official Secrets Act.

‘I haven’t told her yet. I didn’t see that there was any point. Until I actually became one.’

Stevenson smiles.

‘Don’t you think you ought to tell her?’

‘I don’t think it’s necessary at this stage. And I was advised against it by Mr Liddiard. If I advance to the next level, then it would become increasingly difficult to keep things from her.’

‘Yes,’ she says, giving nothing away. Stevenson looks at her watch and her eyebrows hop. ‘Good Lord, look at the time.’

‘Are we finished?’

‘I’m afraid so. I hadn’t realized how late it is.’

‘I thought the interview would last longer.’

‘It can do,’ she replies, uncrossing her legs and allowing her right foot to drop gently to the floor. ‘It depends on the candidate.’

Abruptly I am concerned. The implication of this last remark is troubling. I should have been less candid, made her work harder for information. Stevenson looks too satisfied with what I have given her. She closes my file with knuckles that are swollen with arthritis.

‘So you’re happy with what I’ve told you? Everything’s okay?’

That was a dumb thing to ask. I am letting my concern show.

‘Oh, yes,’ she says, very calmly. ‘Do you have anything else you might want to ask?’

‘No,’ I say immediately. ‘Not that I can think of.’

‘Good.’

She moves forward, beginning to stand. Things have shut down too quickly. She sets my file on a small table beside her chair.

‘I should have thought you were keen to be off. You must be tired after all your exertions.’

‘It’s been hard work. But I’ve enjoyed it.’

Stevenson is on her feet, barely taller than the back of the chair. I stand up.

‘I’ve enjoyed talking to you,’ she says, moving towards the door. There is a distance about her now, a sudden coldness. ‘Good luck.’

What does she mean by that? Good luck with what? With SIS? With CEBDO?

She is holding the door open, a pale tweed suit.

What did she mean?

Brightness in the corridor. I look back into the office to check that I have left nothing behind. But there is only low light and Stevenson’s papers in a neat pile beside her chair. I want to go back in and start again. Without shaking her hand, I move out into the corridor.

‘Good-bye, Mr Milius.’

I turn around.

‘Yes. Good-bye.’

I walk back down the corridor feeling light and stunned. Ogilvy, Elaine, the Hobbit, and Ann are waiting for me in the common room. They stand up and approach me as I come in, a surge of kinship and relief, smiling broadly. This is the thrill of finishing, but I feel little of it. We have all done what we came here to do, but I experience no sense of solidarity.

‘What happened to you, Alec?’ Ann asks, touching my arm.

‘I had a tough one with the shrink. Grilled me.’

‘You look exhausted. Did it go badly?’

‘Difficult to say. Sorry to keep you waiting.’

‘You didn’t,’ Ogilvy says warmly. ‘Matt only finished ten minutes ago.’

I look across at the Hobbit, whose nod confirms this.

‘Pub, then?’ Ogilvy asks.

‘You know what? I may just go home,’ I tell them, hoping they’ll just let me leave. ‘I have to have dinner with a friend later on. I’d like to have a shower, get my head together.’

Elaine appears offended.

‘Don’t be stupid,’ she says. ‘Just have a couple of drinks with us.’