По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

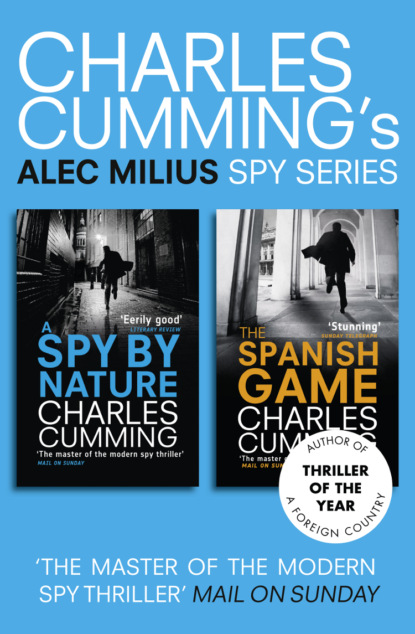

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No, no, not at all, I’d like that very much. I’ll ask him and I’m sure he’d like to.’

‘Good. Shall we set a date?’

‘Okay.’

‘When are you not taken up?’

‘Uh, anytime next week except–just let me check my diary.’

I know that I’m free every night. I just don’t want it to appear that way.

‘How about Wednesday?’

‘Terrific. Wednesday it is. So long as Saul can make it.’

‘I’m sure he’ll be able to.’

Cohen’s eyes are fixed on the far wall. He is listening in.

‘How’s Fortner?’ I ask.

‘Oh, he’s good. He’s in Washington right now. I’m just hoping that he’ll be back in time. He’s got a lot of work to get through out there.’

‘So where shall we meet?’

‘Why don’t we just say the In and Out again? Just at the gate there, eight o’clock?’

She had that planned.

‘Fine.’

‘See you there, then.’

‘I’ll look forward to it.’

I hang up and there is a rush of blood in my head.

‘What was all that?’ Cohen asks, chewing the end of a pencil.

‘Personal call.’

FIFTEEN

Tiramisu

The only spy who can provide a decent case for ideology is George Blake. Young, idealistic, impressionable, he was posted by SIS to Korea and kidnapped by the Communists shortly after the 1950 invasion. Given Das Kapital to read in his prison cell, Blake became a disciple of Marxism, and the KGB turned him after he offered to betray SIS. ‘I’d come to the conclusion that I was no longer fighting on the right side,’ he later explained.

Upon his release in 1953, Blake returned to England a hero. He had suffered terribly in captivity and was seen to have survived the worst that communism could throw at him. There is television footage of Blake at Heathrow Airport, modest before the world’s press, a bearded man hiding a terrible secret. For the next eight years, working as an agent of the KGB, he betrayed every secret that passed across his desk, including Anglo-American cooperation on the construction of the Berlin Tunnel. His treachery is considered to have been more damaging even than Philby’s.

Blake was caught more by a process of elimination than by distinguished detective work. SIS summoned him to Broadway Buildings, knowing that they had to extract a confession from him or he would walk free. After three days of fruitless interrogation, in which Blake denied any involvement with the Soviets, the SIS officer in charge of the case played what he knew was his final card.

‘Look,’ he said, ‘we know you’re working for the Russians, and we understand why. You were a prisoner of the Communists, they tortured you. They blackmailed you into betraying SIS. You had no choice.’

This was too much for George.

‘No!’ he shouted, rising from his chair. ‘Nobody tortured me! Nobody blackmailed me! I acted out of a belief in communism.’

There was no financial incentive, he told them, no pressure to approach the KGB.

‘It was quite mechanical,’ he said. ‘It was as if I had ceased to exist.’

The platforms and escalators of Green Park underground station are thick with trapped summer heat. The humidity follows me as I clunk through the ticket barriers and take a flight of stairs up to street level. The tightly packed crowds gradually thin out as I move downhill towards the In and Out Club.

I am casually dressed, in the American style: camel-coloured chinos, a blue button-down shirt, old suede loafers. Some thought has gone into this, some notion of what Katharine would like me to be. I want to give an impression of straightforwardness. I want to remind her of home.

I see Fortner first, about fifty yards farther down the street. He is dressed in an old, baggy linen suit, wearing a white shirt, blue deck shoes, and no tie. At first I am disappointed to see him. There was a possibility that he would still be in Washington, and I had hoped that Katharine would be waiting for me alone. But it was inevitable that Fortner would make it: there’s simply too much at stake for him to stay away.

Katharine is beside him, more tanned than I remember, making gentle bobbing turns on her toes and heels, her hands gently clasped behind her back. She is wearing a plain white T-shirt with loose charcoal trousers and light canvas shoes. The pair of them look as if they have just stepped off a ketch in St. Lucia. They see me now, and Katharine waves enthusiastically, starting to walk in my direction. Fortner lumbers just behind her, his creased pale suit stirring in the breeze.

‘Sorry. Am I late?’

‘Not at all,’ she says. ‘We only just got here ourselves.’

She kisses me. Moisturizer.

‘Good to see ya, Milius,’ says Fortner, giving me a butch, pumping handshake and a wry old smile. But he looks tired underneath the joviality, far off and jet-lagged. Perhaps he came here directly from Heathrow.

‘I like your suit,’ I tell him, though I don’t.

‘Had it for years. Made in Hong Kong by a guy named Fat.’

We start walking towards The Ritz.

‘So it was great that you could make it tonight.’

‘I was glad you rang.’

‘Saul not with you?’

‘He couldn’t come in the end. Sends his apologies. Had to go off at the last minute to shoot an advert.’

I never asked Saul to come along. I don’t know where he is or what he’s up to.

‘That’s too bad. Maybe next time.’ Katharine moves some loose hairs out of her face. ‘Hope you won’t be bored.’

‘Not at all. I’m happy it being just the three of us.’

‘You gotta girlfriend, Milius?’