По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

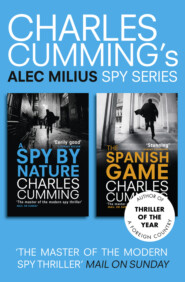

The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Five years ago, almost to the day, I spent my first night in Madrid at this same hotel; a 28-year-old industrial spy on the run from the UK with $189,000 lodged in five separate bank accounts, using three passports and a forged British driving licence for ID. On that occasion I handed a Lithuanian passport issued to me in Paris in August 1997 to the clerk behind the desk. The hotel may have a record of this on their system, so I’m using it again.

‘You are from Vilnius?’ the receptionist asks.

‘My grandfather was born there.’

‘Well, breakfast is between seven thirty and eleven o’clock and you have it included as part of your rate.’ It is as if she has no recollection of having asked the question. ‘Is it just yourself staying with us?’

‘Just myself.’

My luggage consists of a suitcase filled with old newspapers and a leather briefcase containing some toiletries, a laptop computer and two of my three mobile phones. We’re not planning to stay in the room for more than a few hours. A porter is summoned from across the lobby and he escorts me to the lifts at the back of the hotel. He’s short and tanned and genial in the manner of low-salaried employees badly in need of a tip. His English is rudimentary, and it’s tempting to break into Spanish just to make the conversation more lively.

‘This is being your first time in Madrid, yes?’

‘Second, actually. I visited two years ago.’

‘For the bullfights?’

‘On business.’

‘You don’t like the corrida?’

‘It’s not that. I just didn’t have the time.’

The room is situated halfway down a long, Barton Fink corridor on the third floor. The porter uses a credit-card sized pass key to open the door and places my suitcase on the ground. The lights are operated by inserting the key in a narrow horizontal slot outside the bathroom door, although I know from experience that a credit card works just as well; anything narrow enough to trigger the switch will do the trick. The room is a reasonable size, perfect for our needs, but as soon as I am inside I frown and make a show of looking disappointed and the porter duly asks if everything is all right.

‘It’s just that I asked for a room with a view over the square. Could you see at the desk if it would be possible to change?’

Back in 1998, as an overt target conscious of being watched by both American and British intelligence, I ran basic counter-surveillance measures as soon as I arrived at the hotel, searching for microphones and hidden cameras. Five years later, I am either wiser or lazier; the simple, last-minute switch of room negates any need to sweep. The porter has no choice but to return to reception and within ten minutes I have been assigned a new room on the fourth floor with a clear view over Plaza de Santa Ana. After a quick shower I put on a dressing gown, turn down the air conditioning and try to make the room look less functional by folding up the bedspread, placing it in a cupboard and opening the net curtains so that the decent February light can flood in. It’s cold outside, but I stand briefly on the balcony looking out over the square. A neat line of chestnut trees runs east towards the Teatro de España where a young African man is selling counterfeit CDs from a white sheet spread out on the pavement. In the distance I can see the edge of the Parque Retiro and the roofs of the taller buildings on Calle de Alcalá. It’s a typical midwinter afternoon in Madrid: high blue skies, a brisk wind whipping across the square, sunlight on my face. Turning back into the room I pick up one of the mobiles and dial her number from memory.

‘Sofía?’

‘Hola, Alec.’

‘I’m in.’

‘What is the number of the room?’

‘Cuatrocientos ocho. Just walk straight through the lobby. There’s nobody there and they won’t stop you or ask any questions. Keep to the left. The elevators are at the back. Fourth floor.’

‘Is everything OK?’

‘Everything’s OK.’

‘Vale,’ she says. Fine. ‘I’ll be there in an hour.’

TWO

Baggage

Sofía is the wife of another man. We have been seeing each other now for over a year. She is thirty years old, has no children and has been married, unhappily, since 1999. To meet in the Reina Victoria hotel is something that she has always wanted us to do, and with her husband due back in Madrid on an 8 a.m. flight tomorrow, we can stay here until the early hours of the morning.

Sofía knows nothing about Alec Milius, or at least nothing of any hard fact or consequence. She does not know that at the age of twenty-four I was talent-spotted by MI6 in London and placed inside a British oil company with the purpose of befriending two employees of a rival American firm and selling them doctored research data on an oilfield in the Caspian Sea. Katharine and Fortner Simms, both of whom worked for the CIA, became my close friends over a two-year period, a relationship which ended when they discovered that I was working for British intelligence. Sofía is not aware that in the aftermath of the operation my former girlfriend, Kate Allardyce, was murdered in a car accident engineered by the CIA, alongside another man, her new boyfriend, Will Griffin. Nor does she know that in the summer of 1997 I was dismissed by MI5 and MI6 and threatened with prosecution if I revealed anything about my work for the government.

As far as Sofía is concerned, Alec Milius is a typical foot-loose Englishman who turned up in Madrid in the spring of 1998 after working as a financial correspondent for Reuters in London and, latterly, St Petersburg. He has lost touch with the friends he knew from school and university, and both his parents died when he was a teenager. The money they left him allows him to live in an expensive two-bedroom flat in downtown Madrid and drive an Audi A6 for work. The fact that my mother is still alive and that the last five years of my life have been largely funded by the proceeds of industrial espionage is not something that Sofía and I have ever discussed.

What is the truth? That I have blood on my hands? That I walk the streets with knowledge of a British plot against American business concerns that would blow George and Tony’s special relationship out of the water? Sofía does not need to know about that. She has her own lies, her own secrets to conceal. What did Katharine say to me all those years ago? ‘The first thing you should know about people is that you don’t know the first thing about them.’ So we leave it at that. That way we keep things simple.

And yet, and yet…five years of evasion and lies have taken their toll. At a time when my contemporaries are settling down, making their mark, breeding like locusts, I live alone in a foreign city, a man of thirty-three with no friends or roots, drifting, time-biding, waiting for something to happen. I came here exhausted by secrecy, desperate to wipe the slate clean, to be rid of all the half-truths and deceptions that had become the common currency of my life. And now what is left? An adultery. A part-time job working due diligence for a British private bank. A stained conscience. Even a young man lives with the mistakes of his past and regret clings to me like a sweat which I cannot shift.

Above all, there is paranoia: the threat of vengeance, of payback. To escape Katharine and the CIA I have no Spanish bank accounts, no landline phone number at the apartment, two PO boxes, a Frankfurt-registered car, five email addresses, timetables of every airline flying out of Madrid, the numbers of the four phone boxes thirty metres up my street, a rented bedsit in the village of Alcalá de los Gazules within a forty-minute drive of the boat to Tangier. I have moved apartment four times in five years. When I see a tourist’s camera pointed at me outside the Palacio Real, I fear that I am being photographed by an agent of SIS. And when the genial Segovian comes to my flat every three months to read the water meter, I follow him at a distance of no less than two metres to ensure that he has no opportunity to plant a bug. This is a tiring existence. It consumes me.

So there is booze, and a lot of it. Booze to alleviate the guilt, booze to soften the suspicion. Madrid is built for late nights, for bar-crawling into the small hours, and four mornings out of five I wake with a hangover and then drink again to cure it. It was booze that brought Sofía and me together last year, a long evening of caipirinhas at a bar on Calle Moratín and then falling into bed together at 6 a.m. The sex we have is like the sex that everybody has, only heightened by the added frisson of adultery and ultimately rendered meaningless by an absence of love. Ours is not, in other words, a relationship to compare with the one that I had with Kate–and it is probably all the better for that. We know where we stand. We know that one of us is married, and that the other never confides. Try as she might, Sofía will never succeed in drawing me out of my shell. ‘You are closed, Alec,’ she says. ‘Eres muy tuyo.’ An amateur Freudian would say that I have had no serious relationship in eight years as a consequence of my guilt over Kate’s death. We are all amateur Freudians now. And there is perhaps some truth in that. The reality is more mundane; it is simply that I have never met anyone to whom I have wanted to entrust my tawdry secrets, never met anyone whose life was worth destroying for the sake of my security and peace of mind.

Far below, in the square, a busker has started playing alto sax, a tone-deaf cover version of ‘Roxanne’, loud enough for me to have to close the doors of the balcony and switch on the hotel TV. Here’s what’s on: a dubbed Brazilian soap opera starring a middle-aged actress with a bad nose job; a press conference with the government’s interior minister, Félix Maldonado; a Spanish version of the British show Trisha, in which an audience of Franco-era madrileños are staring openmouthed at a quartet of transvestite strippers lined up on stools along a bright orange stage; a re-run on Eurosport of Germany winning the 1990 World Cup; Christina Aguilera saying that she ‘really, really’ respects one of her colleagues ‘as an artist’ and is ‘just waiting for the right script to come along’ a CNN reporter standing on a balcony in Kuwait City being patronizing about ‘ordinary Iraqis’ and BBC World, where the anchorman looks about twenty-five and never fluffs a line. I stick with that, if only for a glimpse of the old country, for low grey skies and the stiff upper lip. At the same time I boot up the laptop and download some emails. There are seventeen in all, spread over four accounts, but only two that are of interest.

From: julianchurch@bankendiom.es

To: alecm@bankendiom.es

Subject: Basque visit

Dear Alec

Re: our conversation the other day. If any situation encapsulates the petty small-mindedness of the Basque problem, it’s the controversy surrounding poor Ainhoa Cantalapiedra, the rather pretty pizza waitress who has won Operación Triunfo. Have you been watching it? Spain’s answer to Fame Academy. The wife and I were addicted.

As you may or may not know, Miss Cantalapiedra is a Basque, which has led to accusations that the result was fixed. The (ex) leader of Batasuna has accused Aznar’s lot of rigging the vote so that a Basque would represent Spain at the Eurovision Song Contest. Have you ever heard such nonsense? There’s a rather good piece about it in today’s El Mundo.

Speaking of the Basque country, would you be available to go to San Sebastián early next week to meet officials in various guises with a view to firming up the current state of affairs? Endiom have a new client, Spanish-based, looking into viability of a car operation, but rather cold feet politically.

Will explain more when I get back this w/e.

All the very best

Julian

I click ‘Reply’:

From: alecm@bankendiom.es

To: julianchurch@bankendiom.es

Subject: Re: Basque visit

Dear Julian

No problem. I’ll give you a call about this at the weekend. I’m off to the cinema now and then to dinner with friends.

I didn’t watch Operación Triunfo. Would rather cook a five-course dinner for Osama bin Laden–with wines. But your email reminded me of a similar story, equally ridiculous in terms of the stand-off between Madrid and the separatists. Apparently there’s a former ETA commander languishing in prison taking a degree in psychology to help pass the time. His exam results–and those of several of his former comrades–have been off the charts, prompting Aznar to suggest that they’ve either been cheating or that the examiners are too scared to give them anything less than 90%.