По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

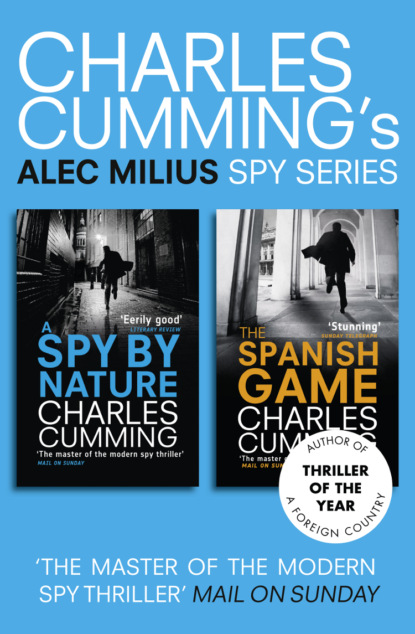

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The trouble is that they don’t give me any indication of how well I’m doing. There’s very little in the way of compliments or praise.’

‘I think people need that, the encouragement,’ Katharine says.

‘That’s right,’ says Fortner, his voice going deep and meaningful. ‘So is that usual for young guys like yourself to get hired by a company and then, you know, just see how it pans out?’

‘I guess so. I have friends in a similar kind of position. And there’s not a hell of a lot we can do about it. It’s work, you know?’

The pair of them nod sympathetically, and, sensing that this is the best opportunity, I decide to tell them now about my interviews with SIS last year. It is a great risk, but Hawkes and I have decided that to tell the Americans about SIS may actually draw me further into their confidence. To conceal the information might arouse suspicion.

‘It’s funny,’ I say, taking a sip of wine. ‘I nearly became a spy.’

Katharine looks up first, vaguely startled.

‘What?’ she says.

‘I probably shouldn’t be telling you, Official Secrets Act and all that, but I got approached by MI6 a few months before I got the job at Abnex.’

Not missing a beat, Katharine says, ‘What is MI6? Like your version of the CIA?’

‘Yes.’

‘Jesus. That’s so…so James Bond. So…are you…I mean, are…?’

‘Of course he’s not, honey. He’s not gonna be sitting here telling us all about it if he’s in MI6.’

‘I’m not a spy, Katharine. I didn’t pass the exams.’

‘Oh,’ she says. ‘I’m sorry.’

‘Why? Why are you sorry?’

‘Well, weren’t you disappointed?’

‘Not at all. If they didn’t think I was good enough for the job, then fuck ’em.’

‘That’s a great attitude,’ Fortner exclaims. ‘A great attitude.’

‘How else am I supposed to react? I went through three months of vetting and interviewing and IQ tests and examinations, and at the end of it all, after they’d more or less told me I was certain to get in, they turned around and shut me out. With a phone call. Not a letter or a meeting. A phone call. No explanation, no reason why.’

My sense of disappointment should be clear to them.

‘You must have been devastated.’

But I don’t want to overplay the anger.

‘At the time, I was. Now I’m not so sure. I had a pretty idealistic view of the Foreign Office, but from what I can gather it’s not like that at all. I had images of exotic travel, of dead drops and seven-course dinners in the Russian embassy. Nowadays it’s all pen pushing and equal opportunities. Right across the board, the Civil Service is being filled up with bureaucrats and suits, people who have no problem toeing the party line. Anybody with a wild streak, anyone with a flash of the unpredictable, is ruled out. There are no rough edges anymore. The oil business has more room for adventure, don’t you think?’

They both nod. It looks as though the gamble has paid off.

‘Sorry. I don’t mean to rant.’

‘No, no, not at all,’ says Katharine, laying her hand on my sleeve. A good sign. ‘It’s good to hear you talk about it. And I have two things I wanna say.’ She refills my glass, draining the bottle in the process. ‘One, I can’t believe that a guy as smart and together as you didn’t make it. And two, if your government doesn’t have sense enough to know a good thing when it sees one, well then, that’s their loss.’

And with that she raises her glass and we do a three-way clink over the table.

‘Here’s to you, Alec,’ says Fortner. ‘And screw MI6.’

While we are eating pudding something odd happens between Fortner and Katharine, something I had not expected to see.

I have been given a large bowl of tiramisu and Katharine is insisting on tasting it. Fortner tells her to leave me alone, but she ignores him, sliding her spoon into the ooze on my plate and retrieving it with her hand held underneath, catching stray droplets of cream.

‘It’s good,’ she says, swallowing, and turns to Fortner.

‘Can I try yours, sweetie?’

He rears back, shielding his bowl with his hand.

‘No way,’ he says indignantly. ‘I don’t want your germs.’

There is a startled pause before she says, ‘I’m your wife, for Chrissakes.’

‘Makes no difference to me. I don’t want any foreign saliva on my mint choc chip.’

Katharine is embarrassed, as am I, and she stands up just a few seconds later to go to the ladies’.

‘Sorry, Milius,’ Fortner grunts, now shamed into regret. ‘I get real touchy about that kinda thing.’

‘I understand,’ I tell him. ‘Don’t worry.’

To smooth things over, he starts telling me a story about how the two of them met, but the ease has gone out of the evening. Fortner knows that he has slipped up, that he has shown me a side of himself he had intended to remain concealed.

‘You want coffee, honey?’ he asks timidly when Katharine comes back. I can tell straightaway that she has forgiven him, gathered herself together in the ladies’ and taken a deep breath. There is no hint of admonishment or frustration on her face.

‘Yeah. That’ll be nice,’ she says, grinning. She has put on a new coat of lipstick. ‘You boys having one?’

‘We are.’

‘Good. Then I’ll have an espresso.’

And the incident passes.

Half an hour later we emerge into the darkness of W1. Fortner, who has picked up the bill, puts his arm around Katharine and walks east, looking around for a cab. The weight of his arm seems to be pulling her down on one side.

‘We gotta do this again sometime,’ she says. ‘Right, honey?’

‘Oh, yeah.’

High up to the left, Katharine gazes at the postcard lights of Piccadilly Circus and says how she never grows tired of looking at them. We walk down the hill towards Waterloo Place and pass the statue commemorating the Crimea.