По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

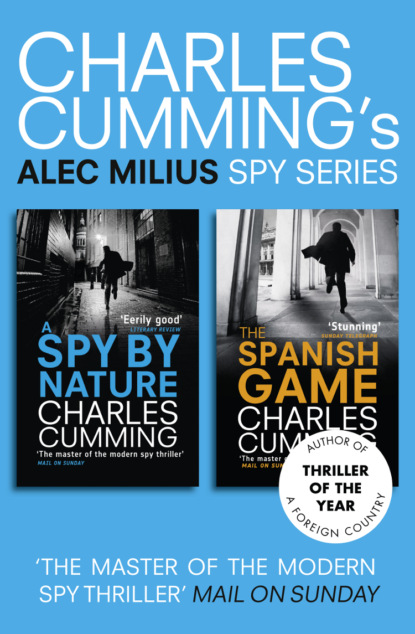

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Good,’ says Lucas, moving outside. ‘Good.’

Alone now in the room, I lift the file from the table as though it were a magazine in a doctor’s surgery. It is bound in cheap leather and well thumbed. I open it to the first page.

Please read the following information carefully. You are being appraised for recruitment to the Secret Intelligence Service.

I look at this sentence again, and it is only on the third reading that it begins to make any sort of sense. I cannot, in my consternation, smother a belief that Lucas has the wrong man, that the intended candidate is still sitting downstairs flicking nervously through the pages of The Times. But then, gradually, things start to take shape. There was that final instruction in Lucas’s letter: ‘As this letter is personal to you, I should be grateful if you could respect its confidentiality.’ A remark that struck me as odd at the time, though I made no more of it. And Hawkes was reluctant to tell me anything about the interview today: ‘Just be yourself, Alec. It’ll all make sense when you get there.’ Jesus. How they have reeled me in. What did Hawkes see in me in just three hours at a dinner party to convince him that I would make a suitable employee of the Secret Intelligence Service? Of MI6?

A sudden consciousness of being alone in the room checks me out of bewilderment. I feel no fear, no great apprehension, only a sure sense that I am being watched through a small panelled mirror to the left of my chair. I swivel and examine the glass. There is something false about it, something not quite aged. The frame is solid, reasonably ornate, but the glass is clean, far more so than the larger mirror in the reception area downstairs. I look away. Why else would Lucas have left the room but to gauge my response from a position next door? He is watching me through the mirror. I am certain of it.

So I turn the page, attempting to look settled and businesslike.

The text makes no mention of MI6, only of SIS, which I assume to be the same organization. This is all the information I am capable of absorbing before other thoughts begin to intrude.

It has dawned on me, a slowly revealed thing, that Michael Hawkes was a Cold War spy. That’s why he went to Moscow in the 1960s.

Did Dad know that about him?

I must look studious for Lucas. I must suggest the correct level of gravitas.

The first page is covered in information, two-line blocks of facts.

The Secret Intelligence Service (hereafter SIS), working independently from Whitehall, has responsibility for gathering foreign intelligence…

SIS officers work under diplomatic cover in British embassies overseas…

There are at least twenty pages like this one, detailing power structures within SIS, salary gradings, the need at all times for absolute secrecy. At one point, approximately halfway through the document, they have actually written: ‘Officers are certainly not licensed to kill.’

On and on it goes, too much to take in. I tell myself to keep on reading, to try to assimilate as much of it as I can. Lucas will return soon with an entirely new set of questions, probing me, establishing whether I have the potential to do this.

It’s time to move up a gear. What an opportunity, Alec. To serve Queen and Country.

The door opens, like air escaping through a seal.

‘Here’s your tea, sir.’

Not Lucas. A sad-looking, perhaps unmarried woman in late middle-age has walked into the room carrying a plain white cup and saucer. I stand up to acknowledge her, knowing that Lucas will note this display of politeness from his position behind the mirror. She hands me the tea, I thank her, and she leaves without another word.

No serving SIS officer has been killed in action since World War Two.

I turn another page, skimming the prose.

The meanness of the starting salary surprises me: only seventeen thousand pounds in the first few years, with bonuses here and there to reward good work. If I do this, it will be for love. There’s no money in spying.

Lucas walks in, no knock on the door, a soundless approach. He has a cup and saucer clutched in his hand and a renewed sense of purpose. His watchfulness has, if anything, intensified. Perhaps he hasn’t been observing me at all. Perhaps this is his first sight of the young man whose life he has just changed.

He sits down, tea on the table, right leg folded over left. There is no ice-breaking remark. He dives straight in.

‘What are your thoughts about what you’ve been reading?’

The weak bleat of an internal phone sounds on the other side of the door, stopping efficiently. Lucas waits for my response, but it does not come. My head is suddenly loud with noise and I am rendered incapable of speech. His gaze intensifies. He will not speak until I have done so. Say something, Alec. Don’t blow it now. His mouth is melting into what I perceive as a disappointment close to pity. I struggle for something coherent, some sequence of words that will do justice to the very seriousness of what I am now embarked upon, but the words simply do not come. Lucas appears to be several feet closer now than he was before, and yet his chair has not moved an inch. How could this have happened? In an effort to regain control of myself, I try to remain absolutely still, to make our body language as much of a mirror as possible: arms relaxed, legs crossed, head upright and looking ahead. In time–what seem vast, vanished seconds–the beginning of a sentence forms in my mind, just the faintest of signals. And when Lucas makes to say something, as if to end my embarrassment, it acts as a spur.

I say, ‘Well…now that I know…I can understand why Mr Hawkes didn’t want to say exactly what I was coming here to do today.’

‘Yes.’

The shortest, meanest, quietest yes I have ever heard.

‘I found the pamphl–the file very interesting. It was a surprise.’

‘Why is that exactly? What surprised you about it?’

‘I thought, obviously, that I was coming here today to be interviewed for the Diplomatic Service, not for SIS.’

‘Of course,’ he says, reaching for his tea.

And then, to my relief, he begins a long and practiced monologue about the work of the Secret Intelligence Service, an eloquent, spare résumé of its goals and character. This lasts as long as a quarter of an hour, allowing me the chance to get myself together, to think more clearly and focus on the task ahead. Still spinning from the embarrassment of having frozen openly in front of him, I find it difficult to concentrate on Lucas’s voice. His description of the work of an SIS officer appears to be disappointingly void of macho derring-do. He paints a lustreless portrait of a man engaged in the simple act of gathering intelligence, doing so by the successful recruitment of foreigners sympathetic to the British cause who are prepared to pass on secrets for reasons of conscience or financial gain. That, in essence, is all that a spy does. As Lucas tells it, the more traditional aspects of espionage–burglary, phone tapping, honey traps, bugging–are a fiction. It’s mostly desk work. Officers are certainly not licensed to kill.

‘Clearly, one of the more unique aspects of SIS is the demand for absolute secrecy,’ he says, his voice falling away. ‘How would you feel about not being able to tell anybody what you do for a living?’

I guess that this is how it would be. Nobody, not even Kate, knowing any longer who I really was. A life of absolute anonymity.

‘I wouldn’t have any problem with that.’

Lucas begins to take notes again. That was the answer he was looking for.

‘And it doesn’t concern you that you won’t receive any public acclaim for the work you do?’

He says this in a tone that suggests that it bothers him a great deal.

‘I’m not interested in acclaim.’

A seriousness has enveloped me, nudging panic aside. An idea of the job is slowly composing itself in my imagination, something that is at once very straightforward but ultimately obscure. Something clandestine and yet moral and necessary.

Lucas ponders the clipboard in his lap.

‘You must have some questions you want to ask me.’

‘Yes,’ I tell him. ‘Would members of my family be allowed to know that I am an SIS officer?’

Lucas appears to have a checklist of questions on his clipboard, all of which he expects me to ask. That was obviously one of them, because he again marks the page in front of him with his snub-nosed fountain pen.

‘Obviously, the fewer people that know, the better. That usually means wives.’

‘Children?’

‘No.’

‘But obviously not friends or other relatives?’