По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

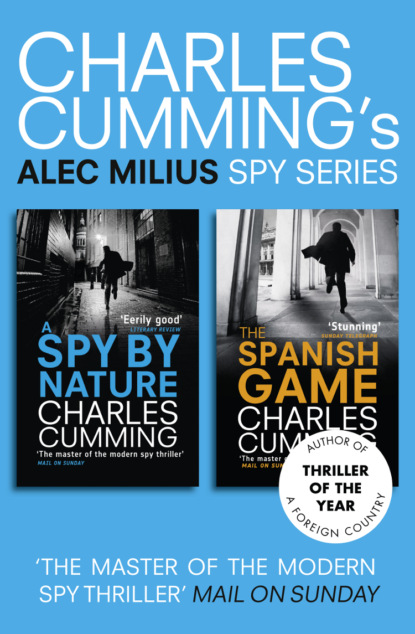

Alec Milius Spy Series Books 1 and 2: A Spy By Nature, The Spanish Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Morning, Nik.’

He swings his briefcase up onto his desk and wraps his old leather jacket around the back of the chair.

‘Do you have a cup of coffee for me?’

Nik is a bully and, like all bullies, sees everything in terms of power. Who is threatening me; whom can I threaten? To suffocate the constant nag of his insecurity he must make others feel uncomfortable. I say, ‘Funnily enough, I don’t. The batteries are low on my ESP this morning, and I didn’t know exactly when you’d be arriving.’

‘You being funny with me today, Alec? You feeling confident or something?’

He doesn’t look at me while he says this. He just shuffles things on his desk.

‘I’ll get you a coffee, Nik.’

‘Thank you.’

So I find myself back in the kitchen, reboiling the kettle. And it is only when I am crouched on the floor, peering into the fridge, that I remember Anna has gone out to buy milk. On the middle shelf, a hardened chunk of overly yellow butter wrapped in torn gold foil is slowly being scarfed by mould.

‘We don’t have any milk,’ I call out. ‘Anna’s gone out to get some.’

There’s no answer, of course.

I put my head around the door of the kitchen and say to Nik, ‘I said there’s no milk. Anna’s gone–‘

‘I hear you. I hear you. Don’t be panicking about it.’

I ache to tell him about SIS, to see the look on his cheap, corrupted face. Hey, Nik, you’re twice my age and this is all you’ve been able to come up with: a low-rent, dry-rot garage in Paddington, flogging lies and phony advertising space to your own countrymen. That’s the extent of your life’s work. A few phones, a fax machine, and three secondhand computers running on outdated software. That’s what you have to show for yourself. That’s all you are. I’m twenty-four, and I’m being recruited by the Secret Intelligence Service.

It is five o’clock in the afternoon in Brno, one hour ahead of London. I am talking to a Mr Klemke, the managing director of a firm of building contractors with ambitions to move into western Europe.

‘Particularly France,’ he says.

‘Well, then I think our publication would be perfect for you, sir.’

‘Publicsation? I’m sorry. This word.’

‘Our publication, our magazine. The Central European Business Review. It’s published every three months and has a circulation of four hundred thousand copies worldwide.’

‘Yes, yes. And this is new magazine, printed in London?’

Anna, back from a long lunch, sticks a Post-it note on the desk in front of me. Scrawled in girly swirls she has written, ‘Saul rang. Coming here later.’

‘That’s correct,’ I tell Klemke. ‘Printed here in London and distributed worldwide. Four hundred thousand copies.’

Nik is looking at me.

‘And, Mr Mills, who is the publisher of this magazine? Is it yourself?’

‘No, sir. I am one of our advertising executives.’

‘I see.’

I envision him as large and rotund, a benign Robert Maxwell. I envision them all as benign Robert Maxwells.

‘And you want me to advertise, is that what you are asking?’

‘I think it would be in your interest, particularly if you are looking to expand into western Europe.’

‘Yes, particularly France.’

‘France.’

‘And you have still not told me who is publishing this magazine in London. The name of person who is editor.’

Nik has started reading the sports pages of The Independent.

‘It’s a Mr Jarolmek.’

He folds one side of the newspaper down with a sudden crisp rattle, alarmed.

Silence in Brno.

‘Can you say this name again, please?’

‘Jarolmek.’

I look directly at Nik, eyebrows raised, and spell out J-a-r-o-l-m-e-k with great slowness and clarity down the phone. Klemke may yet bite.

‘I know this man.’

‘Oh, you do?’

Trouble.

‘Yes. My brother, of my wife, he is a businessman also. In the past he has published with this Mr Jarolmek.’

‘In the Central European Business Review?’

‘If this is what you are calling this now.’

‘It’s always been called that.’

Nik puts down the paper, pushes his chair out behind him, and stands up. He walks over to my desk and perches on it. Watching me. And there, on the other side of the mews, is Saul, leaning coolly against the wall smoking a cigarette like a private investigator. I have no idea how long he has been standing there. Something heavy falls over in Klemke’s office.

‘Well, it’s a small world,’ I say, gesturing to Saul to come in. Anna is grinning as she dials a number on her telephone. Long brown slender arms.

‘It is my belief that Jarolmek is a robber and a con man.’

‘I’m sorry, uh, I’m sorry, why…why do you feel that?’