По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

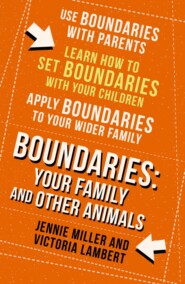

Boundaries: Step One: Me, Myself and I

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Like many psychotherapists and proponents of healthy living, Jennie believes that learning to establish good boundaries is crucial to forming and keeping healthy relationships, with yourself and others. And you may well have heard the term ‘boundaries’ used out loud already – even if you don’t really know what it means – phrases like ‘I need to establish good boundaries for my child around bedtime’ or someone telling you that ‘your work–life balance needs some boundaries.’

But the need to understand and utilise boundaries has never been more acute, and existing advice doesn’t cover many of the situations we now accept and deal with every day.

For example, our fast-paced lives require us to make more decisions than in the past, often quickly – yet with potentially serious consequences. The challenges to our boundaries are more complex and demanding, and we all need new strategies on how to live life as healthily as possible.

The effect of technology on our boundaries is particularly important when it comes to conversations and relationships. These used to be straightforward but now are more difficult because of the lack of face-to-face contact. Situations can easily be misread, moods can be misinterpreted and remarks can be misconstrued when you remove the physical presence of human contact.

The 24/7 culture of e-mails and the Internet means we can never switch off. We are no longer able to pull up the mental drawbridge – we are always vulnerable to what feels like outside pressures and invasions. Some of this attention is not unwelcome, we encourage it ourselves. But that doesn’t mean our boundaries are healthy; it may mean we don’t recognise what can hurt us.

The inspiration for this book came about through a conversation we shared on the subject of e-mail communication. In a steamy coffee shop full of post-school run parents and busy workers grabbing a latte to go, we found ourselves catching up on life, work, family and friends. During our chat, Victoria mentioned a familiar dilemma she was struggling with – she had been asked to help with a function which she had neither the time, energy, or the desire to do. However, she felt a strong pull to be useful and the resulting emotion was guilt. Jennie identified her problem as being a lack of boundaries and explained the concepts that underpin them (as we will explore in this book).

Victoria went home inspired and wrote an e-mail explaining to a colleague why she couldn’t help at the function. She wrote:

‘I am so sorry to say that I feel I cannot help with your plans towards putting on this event. I am really busy with work and childcare at the moment, so am finding it hard to make time. Obviously, I will still do what I can to be useful, and don’t forget to ask me to invite those people we mentioned, but I think that will have to be my input for now. Do call if I can do anything else.’

Then she thought again about Jennie’s explanation of boundaries, and realised she wasn’t being honest. Moreover, she was soft-soaping her decision because she felt guilty – which was confusing the issue, not clarifying it. Several long phone calls with Jennie followed as Victoria was feeling uncomfortable and anxious about the potential response. Jennie encouraged her to be brave and brief.

This was her second draft (with self-boundary): ‘I won’t be available to help with your event. I know it will be a huge success, and wish you well.’

And the response to that second e-mail: ‘Fair enough. Thank you for letting me know. Do come if you can.’

What Victoria found was that waiting for a response to a boundaried e-mail can feel nail-biting. However, as can be seen from the reply, others usually respond surprisingly well to a clear and no-nonsense message.

Think back to the last time you received a clear, concise e-mail. Wasn’t it refreshing and easier to engage with?

You need to know that your boundaries are in your control. You have the ability to decide when and how to draw the line in your life. This will be one of the most empowering lessons you ever learn.

How to Picture a Boundary

Depending on your personality and outlook, you may think of a boundary as an encircling brick wall or perhaps a fresh-looking picket fence with a gate always propped open, but we’d like to invite you to also think of your personal boundary in quite a different way.

Consider human skin. It’s dense enough to protect and contain us, but flexible enough to allow for movement. Skin is porous in the upper layers so what’s necessary can pass through – sweat can be excreted and sunshine absorbed to help us make vitamin D. Skin is also sufficiently tough to withstand accidental damage, and it’s capable of amazing re-growth.

As with skin, we can feel discomfort – even temporary pain at times – when boundaries get damaged either internally or from the outside when we don’t take care. Yet, again like our skin, boundaries are amazing because they can grow with us.

Why have we chosen to use skin as a metaphor? Because skin keeps us in contact with others – it’s not a brick wall or other type of opaque barrier. Studies show that skin-to-skin contact is actually vital for humans. Think of the studies which have shown that ‘kangaroo care’ – the nestling of a naked newborn on its parents’ bare chests – improves outcomes in premature baby care. And equally our skin can act as an early warning system for our entire bodies. Think of how your skin prickles when another person gets too close – it’s a very physical sensation.

Now, let’s look at your own personal boundaries.

EXERCISE: Your Personal Boundary

You will need another person to do this exercise with you. This other should be a friend or colleague but not someone with whom you are very close. We understand this may not feel easy, and you would be more comfortable with someone more familiar to you. But in close relationships, boundaries will be well established. We need you to step outside your comfort zone in order to experience a fresh boundary.

Begin by standing facing each other a comfortable distance apart – this might be four foot away from each other, or more or less.

You are going to stay on your spot. Notice the distance that feels comfortable. Now ask your exercise partner to step closer. They are now in charge of their movements and are gradually going to take one step at a time towards you, pausing for 30 seconds between each step. In that pause, consider how comfortable you feel.

As they come closer, note when you start to feel some level of discomfort. And when do you notice you are really not happy, and that your skin is starting to throw up a few goosebumps? When do you want to scream ‘stop’ – because your personal space now feels properly invaded? At that point ask your partner to step back.

So, what just happened?

This is your body unconsciously registering where it feels most comfortable in relation to another person. This is your discernible physical boundary. Bear this in mind as you read through the book – who oversteps this boundary and who stays too far away?

We suggest you have a notebook to hand while you go through the book so you can write down your experience of exercises like this and ideas that you want to make a note of so you can build up your own Learning Journal as you work through the book.

Part of understanding how to use boundaries is learning to look at interpersonal relationships and your own part in them. Then, deciding where and how to establish a boundary doesn’t just get easier, it becomes self-evident. The exercise above is your first step towards this.

Developing confidence in your own decision-making and its effect on your behaviour will make you happier as it means you are properly owning and taking care of yourself. In our experience: boundaries can give peace of mind. Boundaries give freedom. Boundaries are bliss.

STEP ONE: ME, MYSELF, I (#ulink_a7cdd3e3-5893-5b2a-9669-c768192632c3)

‘The greatest discovery of all time is that a person can change his future by merely changing his attitude.’

OPRAH WINFREY

It is so important that you care for yourself first before you decide how much you can give to or care for another. Self-care is not selfish or even self-centred – quite the opposite. Remember when you get on a plane how the flight attendants tell you – in the case of emergency – to put on your own oxygen mask first, before helping others?

That’s a practical example of self-care – which is clearly aimed at a wider good. Setting self-boundaries is not about ignoring the needs of others, it’s about not ignoring yourself.

Take a minute to notice your reactions to what you have just read. What are your thoughts and feelings? When you read about the oxygen mask, does that make sense?

Can you think of a recent example of an occasion when you have put yourself first? Perhaps it was having an early night when others expected you to stay up to help or entertain them. Maybe you can’t think of an example, but you may know someone who seems confident in putting their needs first (but whom you don’t think of as selfish). You might view them as ‘sorted’ or ‘in control’. Write these initial thoughts down in your Learning Journal.

In Step One, we will learn to create and/or strengthen our personal boundaries which affect sleep, fitness, unhealthy habits, social media and e-mail and our attitude to our ‘self’ in general. We will also introduce a concept called the ‘Drama Triangle’, which explains how you interact with others.

In Jennie’s clinical practice, many clients come with an array of real problems involving other people – such as spouses or children – but what is often underlying is a lack of self-care and a surprising lack of awareness of their own needs. Encouraging them to focus on themselves first makes it easier to tackle their issues with others.

We all benefit from a bit of time and space to reflect on our lives and ourselves. And this book isn’t a replacement for therapy or suggesting anyone needs it. But Jennie knows from more than twenty years in practice – working all over the UK – there are many recurring personal and emotional issues which boundaries can help with.

Have you ever reflected on your personal rules for life – those that dictate things like our bedtimes, eating habits, manners and attitudes to relationships, which all develop over time. These are our ‘self-boundaries’ – and they primarily affect us (though they may well have a knock-on effect on others).

Here, we’ll be exploring our key self-boundaries and explaining how we can set them, taking into account our practical and emotional needs. This is a holistic approach to life – getting into the habit of caring for ourself in all regards. Treating ourself with respect and kindness will change the way we live, before we even start improving relationships with those around us.

We’re going to put you back in charge of your own life, before we go on to explaining how to use boundaries with others.

EXERCISE: Visualise Your Boundary

Read through the following, then start.

Sitting in a comfy chair, take a few deep breaths and close your eyes. Settle yourself. Notice your breathing throughout the exercise.

Now, picture yourself stood in a large field. It is a beautiful sunny day, with blue sky, birds singing and lush green grass underfoot. Take a good look around your field and notice where you are in the field.

As you stand there, imagine that a boundary appears around you. What does it look like? What is it made of? How wide is it? How tall? Is it the same all the way around? Are there doors or windows? How do you feel within your boundary?

Now, imagine your field is becoming populated first with your family, then friends, then work colleagues, and finally everyone in your life, some closer, some further away. The boundary stays in place, but some may be within it and some outside.

Note again how you feel inside your boundary. Who is near to you, and who is far away?