По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

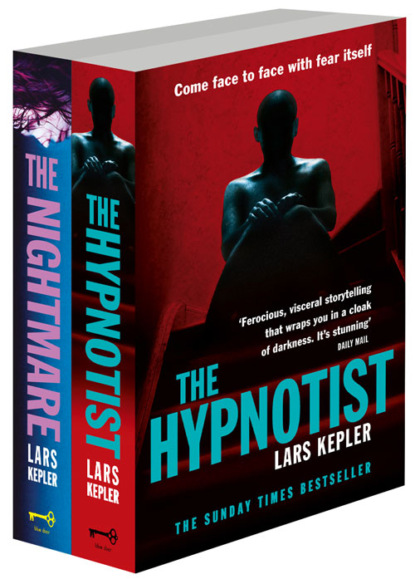

Joona Linna Crime Series Books 1 and 2: The Hypnotist, The Nightmare

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Erik goes on, still smiling. “I wonder how many movies you could get through if you really liked watching them. If you loved movies.”

“Give me a break.” Despite himself, Benjamin smiles.

“Maybe you’d need two TVs, zipping through them all on fast forward.” Erik laughs and places his hand on his son’s knee. Benjamin allows it to remain there.

Suddenly they hear a muffled bang, and in the sky a pale blue star appears, with descending smoke-coloured points.

“Funny time for fireworks,” says Benjamin.

“What?” asks his father.

“Look,” says Benjamin, pointing.

A star of smoke hangs in the sky. For some reason, Benjamin can see Aida in front of him, and his stomach contracts at once; he feels warm inside. Last Friday they sat close together in silence on the sofa in her narrow living room out in Sundbyberg, watching the movie Elephant while her younger brother played with Pokémon cards on the floor, talking to himself.

As Erik is parking outside the school, Benjamin suddenly spots Aida. She’s standing on the other side of the fence waiting for him. When she catches sight of him she waves. Benjamin grabs his bag and, sliding out the car door, says, “’Bye, Dad. Thanks for the lift.”

“Love you,” says Erik quietly.

Benjamin nods.

“Want to watch a movie tonight?” asks Erik.

“Whatever.”

“Is that Aida?” asks Erik.

“Yes,” says Benjamin, almost without making a sound.

“I’d like to say hello to her,” says Erik, climbing out of the car.

“What for?”

They walk across to Aida. Benjamin hardly dares to look at her; he feels like a kid. He doesn’t want her to think he needs his father to approve of her or anything. He doesn’t care what his father thinks. Aida looks nervous; her eyes dart from son to father. Before Benjamin has time to say anything by way of explanation, Erik sticks out his hand.

“Hi, there.”

Aida shakes his hand warily. Benjamin sees his father take in her tattoos: there’s a swastika on her throat, with a little Star of David next to it. She’s painted her eyes black, her hair is done up in two childish braids, and she wears a black leather jacket and a wide black net skirt.

“I’m Erik, Benjamin’s dad.”

“Aida.”

Her voice is high and weak. Benjamin blushes and looks nervously at Aida, then down at the ground.

“Are you a Nazi?” asks Erik.

“Are you?” she retorts.

“No.”

“Me neither,” she says, briefly meeting his eyes.

“Why have you got a—”

“No reason. I’m nothing. I’m just—”

Benjamin breaks in, his heart pounding with embarrassment over his father. “She was hanging out with these people a few years ago,” he says loudly. “But she thought they were idiots, and—”

“You don’t need to explain,” Aida interrupts, annoyed.

He doesn’t speak for a moment.

“I … I just think it’s brave to admit when you’ve made a mistake,” he says eventually.

“Yes, but I would interpret it as an ongoing lack of insight not to have it removed,” says Erik.

“Just leave it!” shouts Benjamin. “You don’t know anything about her!”

Aida simply turns and walks away. Benjamin hurries after her.

“Sorry,” he pants. “Dad can be so embarrassing.”

“He’s right, though, isn’t he?” she asks.

“No,” replies Benjamin feebly.

“I think maybe he is,” she says, half smiling as she takes his hand in hers.

14

tuesday, december 8: morning

The Department of Forensic Medicine is located in a redbrick building in the middle of the huge campus of the Karolinska Institute. And inside the department is the glossy white and pale matt grey office of Nils Åhlén, Chief Medical Officer, aka The Needle.

After giving his name to a girl at reception, Joona Linna is allowed in.

The office is modern and expensive and comes with a designer label. The few chairs are made of brushed steel, with austere white leather seats, and the light comes from a large sheet of glass suspended above the desk.

The Needle shakes Joona’s hand without getting up. He is wearing white aviator-framed glasses and a white turtleneck under his white lab coat. His face is clean-shaven and narrow, the grey hair is cropped, his lips are pale, his nose long and uneven.

“Good morning,” he says, in a hoarse voice.

On the wall hangs a faded colour photograph of The Needle and his colleagues: forensic pathologists, forensic chemists, forensic geneticists, and forensic dentists. They are all wearing white coats, and they all look happy. They are standing around a few dark fragments of bone on a bench; the caption beneath the picture states that this is a find from an excavation of ninth-century graves outside the trading settlement of Birka on the island of Björkö.

“New picture,” says Joona.

“I have to stick photos up with tape,” says The Needle discontentedly. “In the old pathology department they had a picture sixty feet square.”