По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

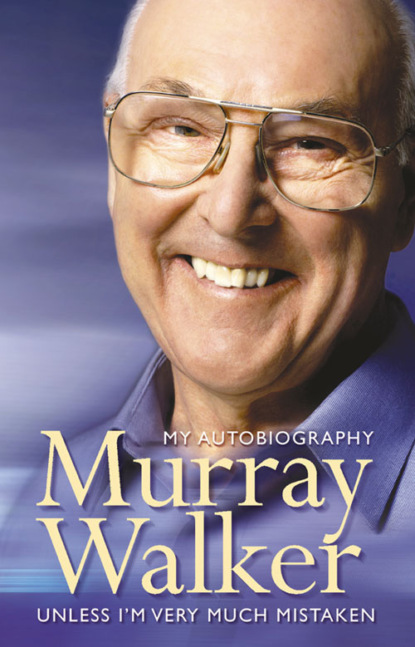

Murray Walker: Unless I’m Very Much Mistaken

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You heard, Murray, think about it.’

The more I thought about it the more I liked it. It made sense even if I wasn’t too sure about whether sole budgies pined for company and what effect multiple budgies would have on their owners. So we worked up a pool of commercials, publicity material and costings and back I went to Melton where I made a sale. It worked – but I never found out what effect it had on the lonely spinsters who kept their bird for company.

Another product that Petfoods and the agency tried to introduce, unsuccessfully this time, was a very high-quality cat food which we decided to brand as ‘Minx’. After all the usual investigatory research it looked as though we had a winner. The formulation was nearly 100% cod (humans turned their noses up at it then) but we were looking for something else to give it a promotable health benefit.

‘How about we put some cod liver oil in it?’ said the Petfoods nutritional experts.

‘Sounds great. Cod liver oil has all sorts of health-giving overtones so we’ll go with that if the research supports it.’

It did and from that came the USP, ‘Minx gives your cat inside satisfaction plus outside protection’. The commercial researched well and the next step was to sell the product to a limited-area test market. Bill Rudd was the Regional Sales Manager and off he went to the big buyers, starting with one of the major Co-operative Societies. His contact there was a grizzled old-timer, and when Bill had gone through all the details including the advertising and the brand’s USP the buyer rang for his secretary.

‘Maisie, I want you to do something for me. Go to the chemist and get me some outside protection and then I’ll give you some inside satisfaction!’

Consternation in court. In all the time we had been working to develop the claim its double entendre had never struck us. We were too close to the product. So we had to start all over again and think of something else. Pity. It might have sold a million.

Masius was a wonderful place to work. A great location in our own modern office block in St James’s Square and a business that was booming. Every year I was there saw a record income and there was a constant buzz of excitement and achievement as new accounts flowed in and very few flowed out. I shared an office and the Mars and Petfoods accounts with a super chap called Ian Pitt who had been a Major during the war and who had been taken prisoner by the Germans. We faced each other across joining desks overlooking the Square and got on like a house on fire. Our job was to underpin and retain the Mars/Petfoods accounts which were of such importance to the agency. We achieved that thanks to help from a lot of fine people. No two days were the same and life was a constant challenge.

In the 1970s Forrest Mars made a further adventurous leap into the unknown when he entered the potato business. As disposable incomes and the desire to spend less time in the kitchen increased, more and more women were buying ready-prepared products like boil-in-the-bag and frozen foods, which needed less preparation. Enter Yeoman Instant Mashed Potato and another new field of endeavour for me. Masius’ job was to create the advertising that would pack Britain’s grocers and supermarkets with hordes of eager housewives fighting to buy and experience this exciting new product that was going to unchain them from having to hump heavy potatoes home, wash, peel, boil and mash them. Fantastic.

‘Yeoman gives you perfect mash – every time!’ the TV advertising declared but the housewives turned out to be frustratingly apathetic about this sensational new product and it made agonizingly slow progress, not made any easier by Cadbury’s ‘Smash’ that blew us into the weeds.

This was the time that there were a lot of IRA bombings and one day when I was in Kings Lynn I said to John McMullen, the Marketing Director, ‘Do you ever have any bomb scares here?’

‘Yes, occasionally, Murray.’

‘What do you do about them?’

‘Do? Nothing. Why?’

‘Isn’t that taking a hell of a chance? What would happen if there really was a bomb?’

‘Listen, Murray, at any time of the day or night we are processing five hundred tons of mashed potato and if the machines are stopped it all goes solid. If you think I’m risking that for a bomb that never was, you’re mistaken.’

Brave words. Unfortunately, John wasn’t too amused when a processing glitch resulted in vast quantities of Yeoman powder being blown out of the factory on to the homes and gardens of Kings Lynn. Good thing it didn’t rain.

Mars were also one of the pioneers of the vending machine business in the UK with a business called Vendepac. We take machines for drinks, cigarettes and confectionery for granted now but food vending was very avant-garde then. To test consumer acceptance, Mars converted the whole of the canteen at Slough to automated food and drink and since everybody, bosses and workers alike, ate there it was inevitable that Vic Hender, the Research Director, would soon be lining up for his automatic lunch. He was not well known for his acceptance of things going wrong and when he stuffed his pre-decimalization half-crown (those were the days!) into the slot for his chicken pie nothing happened. Adopting the time-honoured British procedure, Vic gave the machine an almighty thump, at which point a chap looked out from behind and said, ‘Steady on Guv, I’m putting them in the back as fast as I can!’

One of the agency’s greatest successes, which was in full gallop when I joined, was the Babycham business. One day four men appeared in front of our receptionist, Dorothy Hickie, and said, ‘Our name is Showering. We’re from Somerset and we want to talk to somebody about advertising.’ Before they knew where they were, the Showering Brothers, Francis, Herbert and Ralph, and their nephew Keith, found themselves in Jack Wynne-Williams’ office.

‘There’s nothing in it, Jack,’ said Mike Masius, when he heard that Jack had taken their business on a fee-paying basis. ‘It would cost you more to go and see them in Shepton Mallet than we’d get from the fee.’ Mike wasn’t often wrong but he was this time. For what the Showerings were wanting to market was perry, a drink made from fermented pear juice – a sort of bubbly, pear-based cider. In those days the traditional pub drink for women was still port and lemon, and in those rapidly changing times it was understandably seen as unsophisticated. Masius took the Showerings product and turned it into magic. They put it into small, dark-glass wine bottles with coloured foil tops, called it Babycham, associated it in advertising and promotion with a loveable, animated baby chamois, and provided the pubs with attractive wine glasses carrying the logo and featuring the claim ‘You’d love a Babycham!’

It worked like a charm. The girls could now ask for a seemingly sophisticated, champagne-like, modern drink which wasn’t going to cost their man a fortune and which wasn’t going to get them legless. The pubs and Showerings had a high-profit winner; Masius had a client which coined us money and which, in time, led to a flood of new business as the satisfied Showerings family introduced new products. The Showerings had regular board meetings at the agency’s offices and one December they produced a Christmas-wrapped parcel and said, ‘Jack, as a thank you for all you’ve done at Masius we’ve brought you a present.’

‘Thanks,’ said Jack, ‘that’s very nice of you. It’s usually the agency that buys the client presents in this business. I’m very grateful.’

‘Aren’t you going to open it then?’

When he did he found it contained a car key.

‘And Jack, if you take it to Jack Barclay’s showrooms in Berkeley Square there’s a Rolls-Royce waiting for you to use it in!’

It was an incredible gesture of friendship and appreciation which I’ve never known to be equalled before or since. Jack subsequently gave me the job of getting a personalized registration number for his pride and joy – JWW 347.

I was always at my desk in the West End by 8:00 and seldom home less than 12 hours later. My clients were sophisticated, experienced and demanding and although they were all nice people they didn’t permit any resting on the oars. Each week I was at Melton Mowbray, Slough and Kings Lynn making presentations, taking briefs, maintaining contact and generally keeping in touch with the knowledge that not only were they among the agency’s most important accounts, which our competitors would kill for, but that they were also those that were enabling us to expand outside the UK. From the time I joined in 1959, the mother agency in London was following in the footsteps of the Mars and Colgate organizations by vigorously and successfully expanding, first in Europe and then throughout the rest of the world. As the Mars Empire grew so did ours, for they gave us their business in the new countries they entered on the basis that it was better to use an agency that knew them, even if it didn’t currently have an organization in a new territory, than to use another that didn’t know their ways and products. It was marvellous for us, because not only were we guaranteed an immediate income in any new country we decided to enter but we could offer interesting and exciting promotional opportunities with very real prospects to our many good people who might have left us.

So Masius opened offices in the major European countries – Germany, France, Belgium, Holland, Italy, Spain, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Austria – initially to handle Mars and Colgate brands, but which we could use as bases to pitch for other business. Later we added America, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa to this list, until we became not only the biggest agency in Britain (bigger even than the long-time No. 1, J Walter Thompson) but an enormously desirable partner or takeover target for the mammoth agencies in America like Interpublic. I was eventually to be visiting most of the Masius agencies outside the UK regularly as my responsibilities increased but meantime I was a very busy part of expanding the business in the UK.

In 1964, five eventful years after I had joined the agency, Jack Wynne-Williams made me a proposition. The agency had been in existence for some 21 years, Jack was now in total command, but the old guard on the Board weren’t getting any younger. There was a need to look to the future, for young blood to take over. There were four people whom Jack jokingly referred to as his Young Turks, one of whom was me. None of us were necessarily going to reach the top – in the event only one of us did, and it wasn’t me – but Jack had decided that we had enough potential for him to want to keep us all. One by one he had us into his office to give us all the same message.

‘I’m going to give you a chance to put your money where your mouth is by offering you an opportunity to buy into the agency. It will cost you £30,000 and Warburg, the agency’s bankers, will lend you the money with an annual interest payment of 10% [very reasonable at the time]. You will be obliged to sell the shares when you retire or leave the agency but in the meantime if we continue to do as well as we have in the past the dividends will cover the interest and, in time, the share value growth should more than enable you to repay the loan with a sizeable profit. But, of course, there’s no guarantee. So it is up to you. Think it over and let me know.’

Now, ever since I was a boy my mother, who was very good at playing the stock market, had drummed the basics of it into me. With agency bonuses and other money I had built up a share portfolio of my own and hadn’t done too badly, but this was something else. £30,000 then was the equivalent of not far off £500,000 now and putting myself in debt to that extent was not something that appealed to a naturally cautious chap like me. The agency had done and was doing very well indeed, and there was no reason to suppose that it wouldn’t continue to do so, but it was a very volatile business – its assets were its people, who could leave at short notice, while any contracts that existed with clients weren’t worth the paper they were written on and if they lost confidence in us they would be off like a rocket. On the other hand, the whole of life is a gamble and I was never going to have another opportunity like this.

I talked it over with Elizabeth and in fact neither of us hesitated. The next morning I went back to Jack and said I was on. He told me I’d made a wise decision and he was sure I wouldn’t regret it. I certainly didn’t. From then on there were occasional other share offers as directors retired and sold up, and I bought every one I was offered. My faith and good luck paid off because the agency prospered greatly and everything that Jack had prophesied came to pass. I certainly never made a better financial decision.

Before very much longer I was elevated to the Agency’s small Management Committee and became a theoretical prospect for Managing Director but for very good reasons that was where my agency progress ended. One of those reasons was the fact that my double life as an agency executive and an increasingly busy broadcaster meant that I’d have to give up the latter and devote all my time to the business and there was no way that that was going to happen – I liked my other life too much. But I also had no illusions about whether I was going to be able to reach the top: it mattered more to others than it did to me. I had a very happy life: a happy marriage, a fine home and a broadcasting hobby where I was making consistent progress and which could go on long after I had retired from the business. Things were going very well for me, and as it happened I was about to make a massive change of direction in my agency life.

CHAPTER FIVE Goodbye Mars, Hello Wheels (#ulink_fc112723-87ec-561c-aadc-b5d85e196f71)

Masius was booming, with new business pouring in as a result of its ever-growing reputation. The Imperial Tobacco brand Embassy, with its coupons and gift catalogue, was proving hugely successful, Nescafé (‘Coffee with life in it!’) was a major acquisition and so were many others like Aspro, Woolworths, Wilkinson Sword razorblades, Weetabix and the Beecham Proprietaries’ brands Phensic and Phyllosan (‘Fortifies the over-forties!’), which I looked after. But now, after some nine years working on fast-moving packaged goods, it was as though my first love was calling me home.

Up until now Masius had a foot in all sorts of major product fields but there were still several missing from its portfolio – most notably the car business, which was already sizeable and clearly going to get bigger. So when Vauxhall Cars contacted the agency and invited it to have a look at its business a shiver of excitement went through the building. Vauxhall was not only one of the UK’s leading car brands, it was the British arm of General Motors, the world’s biggest business. If we made a success of Vauxhall, heaven knows what might come of it.

‘I want you to look after this one, Murray,’ said Jack, and I didn’t need a second invitation. This was perfect for me and hopefully the credibility I now had as a motor-sport television and radio personality wouldn’t do our bid any harm with a car manufacturer. We put together a team of the agency’s best research, creative, television and media people and went at it absolutely flat out. After making the best possible presentation we sat back to await the result. And when the call came from Vauxhall Sales Director Geoff Moore at Luton it was good news – we were in! Euphoria all round and for me a pair of engraved gold and ruby cufflinks as a token reward. The joy of knowing that I was going to head up the account was tempered somewhat by the sadness that I would have to come off the Mars/Petfoods business which I had enjoyed so much, but I was looking forward to the new challenge ahead.

It wasn’t easy to do well for Vauxhall, for their cars were seen as dull and Americanized rust buckets. The Viscount was the top model, an upmarket version of the six-cylinder Cresta and, to me, the ultimate soft-suspension, personality-free Squidgemobile. It had everything: plenty of smooth power, automatic gearbox, power brakes and power steering, electric windows, leather upholstery, multi-band radio, the lot. You may get all these things in virtually any car now, but you didn’t then, and the Viscount oozed along with effortless smoothness – but absolutely zilch in the way of automotive charisma. Elizabeth loved it for its luxury, comfort and lack of drama but it didn’t suit my gung-ho self-image at all. I felt 40 years older every time I got in it and in an effort to make it sportier, which it was never meant to be, I had it fitted with a set of the ultimate Pirelli Cinturato radial tyres – the sort that Ferrari used. They didn’t make the slightest difference and since it was designed for crossplies they might even have made it worse. However, I convinced myself that it now steered as though it was on rails.

‘Vauxhall – the big breed!’ had been the blanket theme of our successful presentation and soon after it had been concluded Arthur Martin, the Advertising Manager, said, ‘Let’s go to my office, Murray, and talk about what we are going to say in the advertising.’

Completely poleaxed, I said, ‘Arthur, we’ve been busting our braces for three months to work that out and that’s what we presented.’

‘Oh no, we can’t possibly say that,’ said Arthur, and so after the usual arguments off we went again. It’s when you have to agree with the client that the going can get tough in the agency business. We ended up with ‘The Vauxhall breed’s got style.’ As part of the advertising campaign we were asked to make name recommendations for a new saloon and came up with ‘Ventura’.

‘Like it!’ said Vauxhall, only to come back weeks later saying, ‘Can’t use it. There’s already a Pontiac Catalina Ventura model in the States and the Model Names Committee has given it the elbow.’

‘Hang on,’ I said. ‘You can’t buy a Pontiac in the UK so what’s the problem?’

‘Don’t confuse us with the facts,’ said Vauxhall. ‘Try again.’

So back to the drawing board and a stroke of inspiration. We rounded off the U of Ventura and called it ‘Ventora’. The faceless men in Detroit accepted it and that’s what it was called: ‘Vauxhall Ventora – the lazy fireball!’ It did quite well too: I had one and with its high-torque, easy-going engine it fully lived up to the advertising.

With the agency workers concentrated on the UK I set about getting the Vauxhall business in Europe, such as it was. This was a big mistake, because it wasn’t worth having and with hindsight was never going to be. The Continent was Opel territory and Vauxhall sales there were very small beer. We had an excellent Masius agency in Amsterdam and after I had met and got to know the Vauxhall boss in Holland, John Czarski, we made a successful presentation for what turned out to be an account well worth having. This was more than could be said for France: we presented for the business in Paris and got it, only to find that the previous year’s sales of Vauxhall in France had totalled 47 cars – all of them at greatly reduced prices to GM employees!

It was not a very good start and it didn’t get any better. When I appeared with missionary zeal in Stockholm to present for the Swedish business (which we got), Hugh Austin, the American boss, said, ‘Come with me, Murray, and I’ll show you the sort of problem we have with Vauxhall.’ He took me to the Service Department where there was a factory-fresh Victor with drum brakes on one side and disc brakes on the other. If I hadn’t seen it I would never have believed it.

While all this was going on in work, the rest of my life became increasingly hectic. My parents had moved down to Beaulieu in Hampshire for my father to help Lord Montagu develop his newly founded Montagu Motor Museum and were living in the East Wing at Palace House, in the beautiful New Forest. What started with just a few historic cars in Palace House became the present collection of wonderful vehicles in their own custom-built premises and one of the finest automotive museums in the world. My father was particularly responsible for the motor-cycle section, which I still visit regularly to relive old memories, but the whole collection is well worth the trip, particularly the new exhibition, which I had the honour of opening recently.

Elizabeth and I bought our first house in 1960, the base for my uniquely divided life. Monday to Friday belonged to the agency – and a lot of weekends too when we were working on new business presentations. But almost every weekend was either the BBC’s or ITV’s because for years I worked for both of them on motor-cycle scrambles.