По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

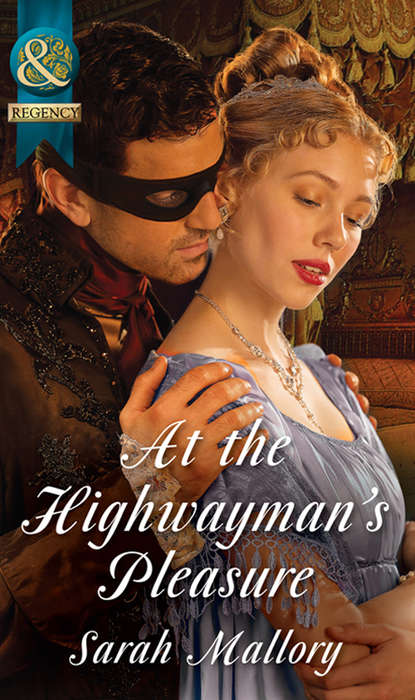

At the Highwayman's Pleasure

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I interrupted your work, sir, I—’

‘It is no matter, the break was very welcome.’ The words were polite, his tone less so. He handed her into the waiting gig and shook out the rug before placing it over her knees. She held her breath, not moving lest he think she objected to his ministrations when in fact it was quite the opposite. A strange, unfamiliar awareness tingled through her body as he tucked the rug about her. She did not want him to stop.

‘It looks like rain.’ He glanced up at the sky before fixing her with his dark, sober gaze. ‘Go directly to Allingford, Mrs Weston. No more exploring today!’

She tried to smile, but her mouth would not quite obey her, not while he was subjecting her to such an intense stare. With a slight nod and a deft flick of the reins she set off out of the yard. The track was straight and the pony needed little guidance. She could easily look back, to see if he was watching her.... No! She sank her teeth into her lip again and concentrated on the road ahead. It was a chance encounter, nothing more. To turn and look back would give Mr Durden completely the wrong idea.

But her spine tingled all the way to the gate of Wheelston Hall and she longed to know if he had watched her drive away.

* * *

Ross stared at the distant entrance long after the little gig had disappeared. He heard Jed come up beside him and give a cough.

‘Who were that lass, Cap’n? I’ve not seen her hereabouts.’

Ross kept his eyes on the gates.

‘That,’ he said, a smile tugging at his mouth, ‘was the celebrated actress Mrs Charity Weston.’

‘Actress, is she?’ Jed hawked and spat on the ground. ‘And were she really explorin’, think ’ee?’

Ross turned and walked back towards the woodpile.

‘She said it was so.’

‘And you invited ’er indoors.’ Ross looked up to find Jed regarding him with a rheumy eye. ‘Never known you to do that afore, Cap’n. Never known you to show any kindness to a woman, not since—’

‘Enough, Jed.’ He beat his arms across his chest, suddenly aware of the cold. ‘If you’ve nothing to do, you can carry that basket of logs indoors and bring me an empty one.’

‘Oh, I’ve plenty to do, master, don’t you fret.’

The old man shuffled away, muttering under his breath. Ross returned to the woodpile and began to split more logs, soon getting into the rhythm of placing a log on the chopping block and swinging the axe. He tried not to think of the woman who had interrupted his work, but she kept creeping into his mind. He found himself recalling the dainty way she held her teacup, the soft, low resonance of her voice, the bolt of attraction that had shot through him when she met his eyes. He had felt himself drowning in those blue, blue eyes.... Ross tore his thoughts away from her only to find himself thinking that the gleaming white-gold centres of the freshly split ash boughs were the exact colour of her hair.

‘Oh, for pity’s sake, get over her!’

‘Did ye call, Cap’n?’ Jed poked his head out of the stable again. ‘Did ye want me to get Robin ready for ye tonight? There’s a moon and a clear sky, which’ll suit ye well...’

‘No. That is—’ Ross hesitated ‘—you may saddle Robin up for me this evening, Jed, but no blacking. I’m going to Allingford!’

Chapter Three

By the time Charity arrived back in Allingford, her disordered emotions had settled into a state of pleasurable exhilaration—very much as they had done after she and some of the other players in Scarborough had made an excursion out of the town and walked on the cliffs overlooking the sea. It had been dangerous, especially for the ladies, because the blustery wind had snatched at their skirts, threatening to drag them off the cliff and dash them into the angry seas below, but the excitement was to see the danger and know that it was just a step away. That same thrill pulsed through her now. It puzzled her and she wondered just what it was about Ross Durden that set her so on edge. He was not conventionally handsome—and she had had experience enough of handsome men in the theatre. He had said nothing that could be construed as improper, yet his very proximity had set the alarm bells ringing in her head.

She was still pondering this conundrum as she left the gig at the stables, and was so lost in thought that she did not notice the Beverleys’ carriage standing outside the gun shop, nor hear Lady Beverley calling to her until she was almost at the carriage door. Charity begged pardon, but Lady Beverley waved away her excuses.

‘No matter, my dear, you are the very person I need.’ She alighted from her carriage. ‘Do you have ten minutes to spare? Sir Mark is inside inspecting a pair of pistols he is minded to buy. He will doubtless be an age yet and I have seen the most ravishing bonnet in the milliners, but I am not at all sure the colour would suit. Would you be an angel and come along to Forde’s with me now and give me your opinion?’

‘Why, yes, if you wish....’

‘Excellent.’ She turned to her footman. ‘Wait here with the carriage for Sir Mark and then tell him to pick me up from the milliner’s on High Street.’ She tucked her arm through Charity’s, saying with a smile, ‘There, that is all settled. Come along, my dear, it is but a step. You shall give me your arm and tell me what it is that has you in such a brown study.’

‘If you must know,’ Charity began as they set off, ‘I was thinking about Mr Durden.’

Lady Beverley stopped to stare at her.

‘Heavens, what on earth has brought this on?’

Charity felt the colour flooding her cheek and gently urged her companion to walk on.

‘I was exploring today and came across the lane leading to Wheelston.’ No need to say she had actually driven to the Hall. ‘It looked so run down and forlorn....’

‘Yes, well, the whole estate is in dire need of repair.’

‘I remember seeing Mr Durden at the reception for my first appearance at the theatre. You said then something had happened to him....’ Charity let the words hang.

Lady Beverley did not disappoint her. She leaned a little closer, saying confidentially, ‘It was such a prosperous estate in old Mr Durden’s time, but after he died the son continued in the navy and left his poor mama to run the place. She was very sickly, you see, and died in... Now, when was it? Two years ago, almost to the day. Young Mr Durden came home to find the place nearly derelict. But then, what did he expect, leaving an ailing woman to look after his inheritance? Quite shameful of him. A dutiful son would have sold out when his mother became so ill. Of course, that is easy for us all to say after the event, and Mr Durden was a very good sailor, I believe. Certainly, he reached the rank of captain and was commended for bravery on more than one occasion, that much I know is true, for it was reported in the newspapers.’

They continued in silence for a few moments and Charity tried to reconcile this picture of Ross Durden with the man she had seen an hour or so earlier.

‘I cannot believe— That is,’ she continued cautiously, ‘he did not look like a man to neglect his duty.’

‘No, well, I believe he was truly grieved when he came back and discovered just how bad things were at Wheelston. But then, if he had shown a little more interest in the place when his mother was alive...’ Lady Beverley stopped. ‘Ah, here we are, my dear, Forde’s, and there is the bonnet I like so much in the window. The green ruched silk, do you see it? Let us step inside and I shall try it on.’

Charity spent the next half hour with Lady Beverley in the milliner’s, and by the time the lady had made her purchase, Sir Mark was at the door with the carriage. Charity realised there would be no more confidences today. She took her leave of her friends and made her way back to North Street, ostensibly to rest and prepare for her performance, although it took all her willpower to force her mind to the play and away from the enigmatic owner of Wheelston.

* * *

The ride into Allingford restored some sense into Ross’s overheated brain. What was he thinking of, paying his hard-earned money for a theatre ticket? He should have been on the road tonight; who knew what luck he might have had? At least there was a chance that fortune might have favoured him, whereas this way he knew that his pocket would be several shillings lighter by the time he went home.

It was madness, he knew that, but having come all the way into Allingford it would be even more foolish to turn round and ride all the way back again without doing something. The thought of risking his money in a gambling den or drinking himself senseless at the George held even less appeal for him.

‘Damnation, I have come this far, I might as well watch the play.’ Savagely he kicked his feet free of the stirrups and slid to the ground. The stable lad at the livery took charge of Robin, and Ross made his way to the theatre. He was early, so he went into a nearby tavern, called for a mug of ale and took a seat by the window, where he had a good view of the theatre’s entrance.

It appeared this comedy was very popular, for a large crowd was gathering. A number of carriages drew up on the street and disgorged the wealthier country gentlemen in smart wool coats and embroidered waistcoats and their fashionable ladies wearing a startling array of headwear, some with so many ostrich feathers that Ross felt a twinge of sympathy for anyone unlucky enough to be sitting behind them that evening. He continued to watch, deriving no little amusement from the scene, then, suddenly, all his senses were on the alert.

A smart travelling carriage had pulled up outside the theatre. Very few people in the area owned such an equipage and he knew of only one who affected a hammer cloth on the box seat. It was pretentious in anyone other than the nobility, but the gentleman Ross had in mind was all pretension. The footman opened the door and Ross’s lip curled as he watched a young woman alight, the flambeaux on the street sparkling off the gold thread in the skirts that peeped from beneath her short, fur-lined cloak. Even at this distance he could see that she was strikingly pretty, with large dark eyes and dark curls that were piled high and adorned with gold ostrich feathers.

Ross felt a surge of loss and regret, but it was quickly succeeded by bitter anger. How could he feel anything more than contempt for the woman after what she had done to him? He stared more closely at her, observed that despite her rosy cheeks and creamy skin, there was a frown between her brows and her mouth was pursed into a look of discontent. She glanced around her with disdain and held up a nosegay as if to protect herself from the offensive smell of the crowd.

Ross turned his attention to the man who followed her out of the coach. He was some years older than the woman, a tall, portly man in a wine-coloured coat with stand-up collar, beneath which his starched neckcloth was so wide it seemed to be holding his head up by the ears, while the ears themselves appeared to be supporting his powdered wig.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: