По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

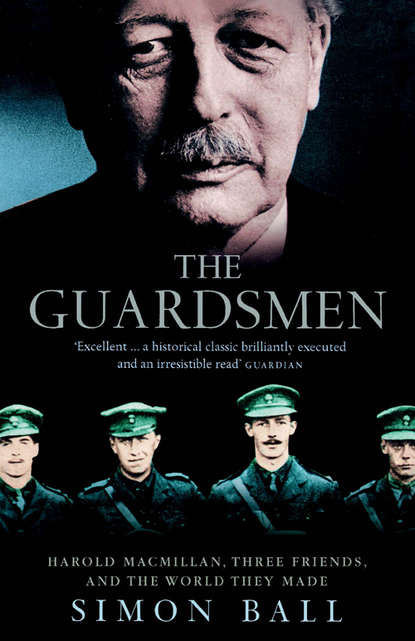

The Guardsmen: Harold Macmillan, Three Friends and the World they Made

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

There were, however, few more decisive ways in which to emerge from the protective carapace of family influence than to join a front-line combat unit on the Western Front. The superior connections of Lyttelton and Cranborne gave them the first crack of the whip. They crossed to France together on 21 February 1915 and joined the 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards, on duty as part of the 4th Guards Brigade in northern France. They were immediately thrown into the classic pattern of battalion life: alternations between the trenches and billets behind the front line. The trenches they found themselves in were also typical of a quiet but active sector. Each side was using snipers and grenade throwers to harass the other and artillery shelled the positions intermittently.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Beyond the physical dangers of trench warfare the most striking feature of their new world was the regimental ‘characters’. These were the regular officers who had joined the Guards in the late 1890s. Their years of peacetime soldiering had inculcated them with the proper Grenadier ‘attitude’. Promotion in peace had been glacially slow. At the time when the new arrivals encountered them they were still only captains or majors, the war being their chance for advancement. By the end of it those that survived were generals. They were attractive monsters, the ideals to which a new boy must aspire.

The second-in-command of the 2nd Battalion was ‘Ma’ Jeffreys, named for a popular madam of his subaltern days. A huge corvine presence, Jeffreys was known for his utter dedication to doing things the Grenadier way. He was a reactionary who regretted that the parvenu Irish and Welsh Guards were allowed to be members of the Brigade of Guards. It should be Star, Thistle and Grenade only in his view.

(#litres_trial_promo) E. R. M. Fryer, another Old Etonian, described by Lyttelton as the ‘imperturbable Fryer’, who joined the 2nd Battalion in May 1915, regretted that ‘Guardsmen aren’t made in a day and I was one of a very small number who joined the Regiment in France direct from another regiment without passing through the very necessary moulding process at Chelsea barracks’. He found himself being given special, and not particularly enjoyable, lessons by Jeffreys on how to be a Grenadier.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Jeffreys was considered to be ‘one of the greatest regimental soldiers’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Many years after the fact, Lyttelton admired Jeffreys as an example of insouciant courage. A runner was missing and Jeffreys, accompanied by his orderly ‘in full view of the enemy and in broad daylight, strode out to find him, and did find him. By some chance, or probably because the enemy had started to cook their breakfasts, he was not shot at. Such actions are not readily forgotten by officers or men, and the very same second-in-command, who had without any question risked his life…would have of course damned a young officer into heaps for halting his platoon on the wrong foot on the parade ground.’

(#litres_trial_promo) While he was serving with him, however, he admired him as a courageous realist: ‘He is exceedingly careful of his own safety,’ he noted in June 1915, ‘where precautions are possible, but where they are not courageous. Any risk where necessary, none where not.’ When his commanding officer was killed at Festubert, he showed no emotion: ‘after seven months in the closest intimacy with a man whom he liked, you might have thought that that man’s death by a bullet which passed through his own coat would have shaken him. Not at all.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

‘Boy’ Brooke, who was brigade-major of the 4th Guards Brigade and later CO of the 3rd Battalion Grenadier Guards, never spoke before luncheon. He treated his subordinates to ‘intimidating silences, when the most that could be expected was a curt order delivered between clenched teeth, derived from a slow acting digestion, which clothed the world in a bilious haze until the first glass of port brought a ray of sunshine’. After luncheon he was ‘charming, helpful and humorous’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Boy could take a dislike to a junior officer. One such, who was ‘rather over-refined and a fearful snob’, ‘should not’, he believed, ‘have found his way into the regiment’. Arriving at the end of a five-hour march, Brooke could not find his billeting party. Eventually the officer ‘emerged from an estaminet, and gave some impression of wiping drops of beer from his moustache. He came up and saluted, and not a Grenadier salute at that. His jacket was flecked with white at the back’ from sitting against the wall of the pub, ‘“Ay regret to inform you, Sir, that the accommodation in this village is quite inadequate”.’ To which Brooke replied, ‘“Is that any reason you should be covered with bird-shit?”’ and had him transferred.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Lord Henry ‘Copper’ (he was red-haired and blue-eyed) Seymour and ‘Crawley’ de Crespigny, a family friend of the Cecils, were 2nd Battalion company commanders in 1915. Lord Henry had had to take leave of absence from the regiment because of his gambling debts. As a result he had been wounded early in the war while leading ‘native levies’ in Africa. He evaded a medical board and found his way to France. His wounds had not healed and needed to be dressed regularly by his subalterns. He was a notorious disciplinarian.

De Crespigny was also a fierce disciplinarian on duty but notoriously lax off duty with those he liked. He had been a well-known gentleman jockey, feared for having horse-whipped a punter who suggested he had thrown a race. Since his best friend was Lord Henry, he was known to treat officers with gambling debts lightly while damning anyone who reported any of them as a bounder. He suffered greatly with his stomach as a result of the alcoholic excess of his early years.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘Hunting, steeplechasing, gambling and fighting were “Crawley’s” chief if not only interests’, remembered Harold Macmillan. Macmillan ‘never saw him read a book, or even refer to one. To all intents and purposes, he was illiterate.’ Even when ordered to desist, because they made him too visible, ‘Crawley’ always wore gold spurs.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Whatever private thoughts Lyttelton and Cranborne had about their new life, they kept up a joking façade for their families back in England: ‘The worst of it is that the hotel is very bad,’ Lyttelton reported to Cranborne’s mother, ‘if (as Bobbety and I have hoped) we come to explore the fields of battle after the war with our respective families en masse we shall have to look elsewhere for lodging. By Jove how we shall “old soldier” you.’

(#litres_trial_promo) A ten-day stay in Béthune, punctuated by light-hearted ‘regimentals’, boxing matches and concert parties, was merely a prelude to more serious business.

On 10 March 1915 the 4th Guards Brigade marched north to take part in an attack around Neuve Chapelle. The attack proved to be a bloody disaster. Luckily for the new officers they did not take part. Twice the battalion prepared to go over the top but twice was ordered to stand down. Within their first three weeks at the front, Cranborne and Lyttelton experienced manning the front line, the off-duty regimental routine and the nightmarish possibilities of the offensive. The horrors of war were all too apparent. The battalion returned to trenches near Givenchy that were neither deep enough nor bulletproof. The experience was nerve-jangling. German artillery and mortar fire was effective against these trenches. On one occasion such fire was induced for frivolous reasons: the Prince of Wales visited the battalion and ‘tried his hand at sniping, and…there was an immediate retaliation’. The threat of mines was constant: ‘everyone was always listening for any sound’. In May the first reports of German gas attacks further north at Ypres arrived and there were desperate attempts to rig up makeshift respirators. The visible landscape was grim. ‘The village was a complete ruin, the farms were burnt, the remains of wagons and farm implements were scattered on each side of the road. This part of the country had been taken and re-taken several times, and many hundreds of British, Indian, French and German troops were buried here.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Givenchy was also their first sight of ‘war crimes’ or ‘Hun beastliness’. Anyone wounded in trench raids was hard to recover. The Germans fired at the stretcher bearers who tried to reach them. Cases occurred ‘of men being left out wounded and without food or drink four or five days, conscious all the time that if they moved the Germans would shoot or throw bombs at them. At night the German raiding parties would be sent out to bayonet any of the wounded still living.’ It is unclear whether the ‘beastliness’ was solely on the German side. Certainly by 1916 there were clear instances of the British refusing to take prisoners on the grounds that ‘a live Boche is no use to us or to the world in general’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Indeed, a memoir written by a private in the Scots Guards about his experiences later in the war was at the centre of German counter-charges in the 1920s about British ‘war crimes’. The private, Stephen Graham, reported that the ‘opinion cultivated in the army regarding the Germans was that they were a sort of vermin like plague-rats and had to be exterminated’. He provided an anecdote set near Festubert, where both Lyttelton and Cranborne fought: ‘the idea of taking prisoners had become very unpopular. A good soldier was one who would not take a prisoner.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Even leaving aside ‘war crimes’, the fighting was desperate and personal. Armar Corry, an Eton contemporary of Lyttleton and Cranborne, led a wire-cutting party that ran into a German patrol. Corry shot one of the Germans, as did his sergeant. His private threw a grenade. The German officer leading the patrol drew his pistol and shot Corry’s sergeant, corporal and private. With his entire party dead, Corry fled for his life.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Whatever the extent of the brutalization Lyttelton and Cranborne were undergoing, they were certainly becoming cynical about their senior commanders. In March a printed order of the day arrived over the name of Sir Douglas Haig, who was immediately pronounced an ‘infernal bounder’. There was ‘much angry comment’ from the junior officers about Haig’s ‘bombastic nonsense’. Looking out from his trench, Lyttelton commented: ‘the attacks on Givenchy had failed…I know the position from which these attempts were launched and a more criminal piece of generalship you cannot imagine.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Five days after the launch of the Festubert offensive in May, Lyttelton wrote: ‘There is some depression among the officers at the great offensive…We are rather asking ourselves: if we can’t advance after that cannonade how are we to get through?’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Their anger at and fear of the incompetence of the army commander was mitigated, however, by a continued belief in the superiority of the Guards. The Indian troops and the Camerons alongside whom they fought may have ‘showed the utmost gallantry in the attack, but their ways are not ours at other times. When it comes to bayonet work they are as courageous as we are, but they haven’t got the method, the care or the discipline to make good their gains, or show the same steadiness as the Brigade.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Lyttelton and Cranborne were also buoyed up by each other’s company. ‘I had a very amusing talk with Bobbety yesterday,’ Oliver wrote in April, ‘we nearly always have a good crack now and great fun it is. The more I see of him the more I like him.’ The two young men found themselves convulsed by laughter at the thought that the pictures on the date boxes they received in their food parcels looked exactly like the paintings of an ‘artistic’ acquaintance of theirs, Lady Wenlock.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Although the Guards Brigade had seen plenty of action since Lyttelton and Cranborne joined their unit in February, it had been used as a support formation rather than an assault unit. The 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards was finally committed to lead an attack on 17 May 1915, eight days after the beginning of the battle of Festubert. Lyttelton and Cranborne had the chance of a brief conversation before the battle began. They were, Lyttelton wrote, ‘pretty cheerful as it was clear that we were in the course of wiping the eye of the rest of the army and justifying the German name of “the Iron Division”’.

(#litres_trial_promo) They began moving up at 3.30 in the morning in extremely difficult conditions. The Germans were shelling all the roads leading towards the trenches so the battalion had to move at snail’s pace in dispersed ‘artillery formation’ over open ground. Confusion reigned. ‘When it reached the supports of the front line, it was by no means easy to ascertain precisely what line the Battalion was expected to occupy. Units had become mixed as the…result of the previous attack, and it was impossible to say for certain what battalion occupied a trench, or to locate the exact front.’

It was not until late afternoon that the battalion started to move towards the actual front line. The route was clogged in mud and it was dark before they reached the front trenches. ‘The men had stumbled over obstacles of every sort, wrecked trenches and shell holes, and had finally wriggled themselves into the front line.’ The German trenches captured on the previous day which they passed over ‘were a mass of dead men, both German and British, with heads, legs and other gruesome objects lying about amid bits of wire obstacles and remains of accoutrements’.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘It was a night,’ Lyttelton recalled a week later, ‘I shall never forget.’ The encounter with such carnage sickened him but ‘only turned me up for about ten minutes. After that,’ he admitted, ‘you cease to feel that you are dealing with what were once men…We were trying to drag a body out – it had no head – and I found by flashing a light that one of my fellows was standing on its legs. So I said, “Get off. How can we get it out if you stand on it, show some sense.” Then I flashed my light behind me and I found I had both feet on a German’s chest who had [been] nearly trodden right in.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The advance had been so difficult that the commanding officer, Wilfred Smith, decided that he could not launch his attack on the position known as ‘La Quinque Rue’ as he had been ordered. He decided instead to wait until dawn. Ma Jeffreys was put in charge of the front line, commanding 2 and 3 Companies. Cranborne was commanding a platoon in 2 Company with Percy Clive, a Conservative MP serving as a ‘hostilities only’ officer, as his company commander. Held in reserve were 1 and 4 Companies. Lyttelton was thus further back with his platoon in 4 Company, commanded by ‘Crawley’ de Crespigny.

The 18th of May dawned misty and wet. Visibility was so bad that the attack was postponed once more. They lay in their waterlogged scrapes all day. Suddenly at 3.45 in the afternoon a peremptory order arrived to attack at 4.30 p.m. Jeffreys had to make hurried preparations. He decided to launch the assault using 3 Company, with one platoon of 2 Company under Cranborne in support. Haste proved fatal. The attacking force was decimated. A short artillery bombardment failed to knock out the German machine-guns. As a result ‘the men never had any real chance of reaching the German trenches…the first platoon was mown down before it had covered a hundred yards, the second melted before it reached even as far, and the third shared the same fate’. Armar Corry was the only officer in the company to survive.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Cranborne, however, cheated death. He did not lead his platoon forward into this maelstrom. Indeed, he was rendered unfit to do anything by the noise of the battle. Accounts differ about what rendered him hors de combat. The regimental history records that he was ‘completely deafened by the shells which burst incessantly round his platoon during the attack’.

(#litres_trial_promo) His own medical report, based on a doctor’s examination on 26 May, states: ‘Near Festubert on 18 May 1915, he became deaf from the noise of rifle fire close to his left ear. He also had “ringing” noises in that ear.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Near the stunned Cranborne a fierce argument raged between the remaining officers of the battalion. Percy Clive, Cranborne’s company commander, had realized that the attack was a senseless massacre. When Ma Jeffreys ordered him to lead 2 Company forward once more, Clive refused to obey on the grounds that to advance was plainly suicidal. As a result the battalion stayed put. As the casualties, including Cranborne, were evacuated, the brigade major, ‘Fat Boy’ Gort, came up to investigate. Gort, ‘the bravest of the brave’, who finished the war bedecked with medals including the Victoria Cross, agreed with Clive. Lord Cavan, the Grenadier commander of the 4th Guards Brigade, ordered the battalion to dig in where it lay – they had advanced about 300 yards and come up short of their objective by about 200 yards.

(#litres_trial_promo)

That night Lyttelton moved up with 4 Company to relieve the shattered remnants of 3 Company: ‘it was pitch dark, raining and cold’. He and another officer went out to try and recover some of the wounded. ‘It was a bad job. Some of these fellows had crawled into shell-holes about twenty feet deep and getting them out was a critical business.’ ‘The whole place,’ wrote Lyttelton as he tried to piece together his experiences afterwards, ‘was a sea of mud, and the scene still remains incoherent in my memory, plunging about for overworked stretcher bearers, falling into shell-holes, losing our way, wet and tired, we felt all the time rather impotent.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Opinion among the surviving battalion officers was that the whole affair had been mismanaged. The generals had bungled in ordering them to attack on the afternoon of the 18th with so little warning.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The battle of Festubert convinced the relatives who had been instrumental in getting men into the Guards that service with a combat infantry battalion on the Western Front was not necessarily a good idea. When Cranborne was shipped home, it was discovered that his injuries were not serious and that he would soon be able to rejoin his regiment. ‘The ear,’ his medical board was told, ‘has been examined by a specialist and has been diagnosed as a course of labyrinthine deafness; prognosis good.’

(#litres_trial_promo) He was granted three weeks’ leave. While he was on leave the Cecils’ family doctor diagnosed him with appendicitis. His friends regarded this as an amazing stroke of luck,

(#litres_trial_promo) as was clear from the letters of commiseration he received. It must be sore having a bad ear and a bad gut: ‘But,’ one friend serving with a line infantry regiment in France, added, ‘I wonder if you are sorry. For goodness’ sake don’t come out here again.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Lyttelton cheerfully chipped in, ‘There is a great deal of satisfaction in hearing from someone whom you have just seen in Flanders, at Park Lane.’