По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

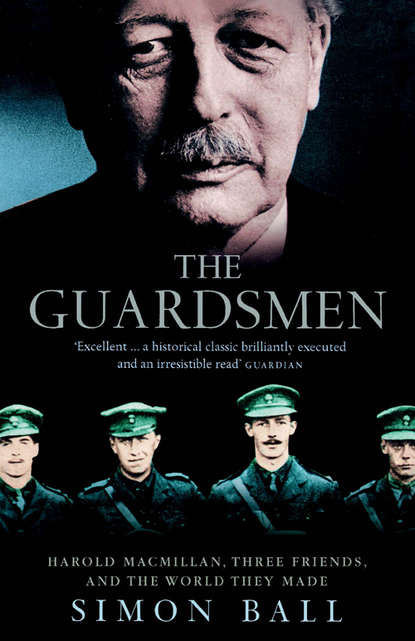

The Guardsmen: Harold Macmillan, Three Friends and the World they Made

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

By early 1916 Lyttelton had sloughed off any hint of boyishness. He was an experienced soldier who had had responsibility beyond his years thrust upon him. His letters home were detailed, hard-edged and often cynically funny. Macmillan, on the other hand, retained a certain pompous innocence: he didn’t ‘know why I write such solemn stuff’ but write it he did. The army possessed that ‘indomitable and patient determination, which has saved England over and over again’. It was ‘prepared to fight for another 50 years if necessary until the final object is attained’. The war was not just a war, it was ‘a Crusade’: ‘I never see a man killed but think of him as a martyr.’

(#litres_trial_promo) He found the words of the French high command at Verdun – resist to the last man, no retreat, sacrifice is the key to victory – so stirring that he copied them into his field pocketbook. Whereas Lyttelton had felt the prick of ambition, Macmillan had to deflect his mother’s demands that he should get on. His ambition was to survive and ‘get command of a company some day’, though he disparaged his mother’s wish that he should get out of the front line to ‘join the much abused staff’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Macmillan and Crookshank were finally united in mid June near Ypres. Crookshank had slowly made his way to the battalion in an ‘odd kind of procession’, braving the danger of inadequate messing facilities, ‘perfectly abominable…a disgrace to the Brigade’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Each was delighted to see the other. If they had to be in this awful place, it was at least some solace to tackle the task ahead with your closest friend. They immediately became tent-mates.

(#litres_trial_promo) Crookshank was assigned to his old platoon: ‘rather like going to school after the holidays seeing so many of the old faces after the long absence’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Crookshank believed he had done rather well in the battalion the previous year and was much less self-deprecating than Macmillan about his chances of promotion. He was thus ‘very annoyed and disappointed’ when both of them were transferred into 3 Company under the command of another subaltern, Nils Beaumont-Nesbitt.

(#litres_trial_promo) In early July they went into the ‘Irish Farm’, ‘one of the worst positions [the battalion] had been in’. It offered 1,300 yards of ‘trenches’ that were ‘mainly shell holes full of water with no connecting saps, constant casualties and back-breaking work.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Raymond Asquith described it as ‘the most accursed, unholy and abominable place I have ever seen, the ugliest, filthiest most fetid and most desolate – craters swimming in blood, dirt, rotting and swelling bodies and rats like shadows…limbs…resting in the hedges’. The aspect that disturbed him most was ‘the supernaturally shocking scent of death and corruption [so] that the place simply stank of sin and all Floris could not have made it sweet’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Crookshank escaped the worst by being sent on a Lewis gun course at Étaples, ‘mechanism cleaning and stripping (I did but very slowly)’, although he encountered another mess that was the ‘absolute limit – had some words with the CO on the subject of servants, went to dine at the Continental’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Crookshank was a fusspot. He liked things just so. His doting mother made sure that he was never short of funds to make himself comfortable. As a result his girth was beginning to swell. He was lucky to have in such close attendance Macmillan, who always appreciated the waspish humour with which he leavened his perpetual moaning. Although Crookshank’s undoubted bravery won him friends, he could be an irritating companion in those trying circumstances.

Macmillan himself, on the other hand, having had little opportunity to shine during his last spell at the front, ‘made his name’ from the battalion’s unpromising position. On 19 July he led two men on a scouting patrol in no man’s land. They managed to get quite near the German line, but then ran into some German soldiers digging a sap. A German threw a grenade, the explosion from which wounded Macmillan in the face. One of his men was also wounded and they struggled back to the British lines.

(#litres_trial_promo) Macmillan’s wound was serious enough for him to have left the battalion, but he refused to do so out of a mixture of bravado and opportunism piqued by Crookshank’s more militant attitude to promotion. ‘My first duty is to the Regiment which I have the honour to serve,’ he decided, ‘and not only are we very short of officers of any experience just now…but I was told confidentially by the Adjutant the other day that the commanding officer would probably give me command of the next company vacant, when I had had a little more experience of trench work.’ Macmillan was mentioned in dispatches for his bravery, but more immediately he basked in the good opinion of de Crespigny, who ‘was pleased with me for staying’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

They all nevertheless knew that these skirmishes in Flanders were a mere sideshow, overshadowed by ‘der Tag – the first day of the great Fourth Army and French push’ on the Somme, leagues away to the south.

(#litres_trial_promo) As far as they could tell, ‘the Somme seems to be progressing favourably, if slowly and methodically’. They were all too aware that ‘the casualties have been very heavy’.

(#litres_trial_promo) In fact the first and indeed subsequent days of the Somme offensive were a bloody disaster. As the Guards Division was sent marching south, GHQ acknowledged that the loss of men was unsustainable. The Fourth Army would revert to a ‘wearing out’ battle until the ‘last reserves’, of which the Guards were part, could be thrown into a renewed ‘decisive’ attack in mid September.

(#litres_trial_promo) News of these disasters soon filtered down to the junior officers and undermined their initial optimism.

(#litres_trial_promo) One subaltern in their company was court-martialled for sending an ‘indiscreet’ letter, opened by the censors, criticizing the staff. It was rumoured that this letter was the reason why King George had not inspected the battalion when he visited the Guards at the beginning of August. It was noted that the Prince of Wales, so obvious a presence the previous year, was no longer anywhere to be seen near the battalion.

(#litres_trial_promo)

On the road Crookshank and Macmillan ‘were having very amusing conversations’. The northern part of the Somme battlefield was even ‘quite a nice change after Ypres’. There was a ‘wonderful view all round especially of the Thiepval plateau’, which they observed for hours. The trenches were very good. Crookshank and Macmillan were even allocated their own dugout, although it proved to be less than a blessing, located at ‘the end of a communications trench junction and well shelled’. They abandoned it after only one night.

(#litres_trial_promo) Indeed, it was at night that they had time to mull over the grimness of their situation. Sitting in their shared tent, they were ‘frightfully depressed’ by the fact that their ‘most intimate circle [had been] killed in the push, it’s enough to make anybody feel very sad’. Crookshank was particularly upset by the death of his ‘great friend’ at Magdalen, Pat Harding. Harding, a ‘great Oxford friend’ of Macmillan as well, had already risen to rank of major in a Scottish regiment before he was killed. Not only was the war cruel, it was insidious. Arthur Mackworth, for instance, a young classics tutor who had taught Crookshank at Magdalen, and who escaped the front after being transferred from the Rifle Brigade to the War Office Intelligence Department because of a heart condition, was so tormented by insomnia that he shot himself dead.

They had little time to dwell on these tragedies: they were soon in the midst of a major training programme that continued throughout August and into September to prepare the Fourth Army for its second great push on the Somme. Something of the kind had been tried before Loos, but this was on a much bigger scale. The Fourth Army tried to learn the lessons of the first phase of the offensive and inculcate its troops with the best ways of carrying out trench attacks and of using their equipment.

(#litres_trial_promo) One change of doctrine in the summer of 1916 affected Macmillan. Initial operations on the Somme led to a reversal of Haig’s post-Loos enthusiasm for the grenade and a return to the doctrine that ‘the rifle and the bayonet is the main infantry weapon’. Supposedly, ‘when attacking troops are reduced to bombing down a trench, the attack is as good as over’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Guards nevertheless still put considerable emphasis on grenade training, and as their attack at Ginchy was to show, front-line troops would remain deeply attached to their grenades whatever the official prognostications. Macmillan, however, was not called on to resume the role of bombing officer, which he had managed to abandon just before the beginning of the march south. Crookshank’s Lewis guns remained in vogue. Ma Jeffreys descended on a tour of inspection and told him in no uncertain terms that the machine-guns would play an important role and he would be leading the gun team.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At the beginning of September the whole tempo of preparations stepped up.

(#litres_trial_promo) Crookshank’s impression, after he and Macmillan had walked the ground together, was that the Loos battle they had taken part in during the previous September ‘didn’t start to be compared with this’.

(#litres_trial_promo) They were in ‘a glorified camp and depot for every kind of stores’, he recorded in an unsent letter. ‘One can hardly see a square yard of grass, it is absolutely thick and swarming with men, tents and horses…as for the guns they are past counting battery after battery of big ones…with mountains of ammunition and a light railway to supply it. It certainly was a revelation,’ he concluded, ‘and shows that we really have begun fighting now.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Guards Division was deployed as part of Cavan’s XIV Corps on the south of the Somme front. Its mission was to move forward from the village of Ginchy, just to the south of Delville Wood, which still contained Germans, to the village of Lesboeufs to the north-east. On 11 September the detailed attack orders arrived.

(#litres_trial_promo) Crookshank held a Lewis gun parade ‘to tell off the different teams’. His own team consisted of a sergeant, four corporals and twenty-four men servicing four Lewis guns.

(#litres_trial_promo) On 12 September the 3rd Battalion moved up into the line, so that Lyttelton was posted only a few hundred yards to the right of Macmillan and Crookshank.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was Macmillan who went into action first. German machinegunners were positioned in an orchard on the northern edge of Ginchy. It was clear the moment the Guards started to advance they would be machine-gunned in the flank. On the night of 13 September de Crespigny ordered 4 Company, supported by two platoons of 3 Company, commanded by Macmillan, to clear the Germans out of the orchard.

(#litres_trial_promo) The attack took place in bright moonlight and in the face of heavy German fire; ‘it was very expensive, as they found better trenches and more Germans than expected’.

The next day, the 14th, ‘was terrible’. The 2nd Battalion’s trenches suffered a direct hit from a twenty-eight inch bomb. Many were buried alive and a company commander had to be relieved because of shell shock.

(#litres_trial_promo) ‘That day,’ wrote Lyttelton, ‘dawdled away.’ Towards evening the word came down that H-hour was 6.20 a.m. the next day. ‘Action,’ Lyttelton recorded. ‘Changed into thick clothes, filled everything with cigarettes. Put on webbing equipment. Drank a good whack of port. Looked to the revolver ammunition.’ They moved into position that night. It was bitterly cold. They looked ‘out into the moonlight beyond into the most extraordinary desolation you can imagine’. ‘The ground,’ Lyttelton wrote, ‘is like a rough sea, there is not a blade of grass, not a feature left on that diseased face. Just the rubble of two villages and the black smoke of shells to show that the enemy did not like losing them…the steely light of the dawn is just beginning to show at 5.30.’

This moonscape, devoid of landmarks, was to prove a terrible problem. Officers had their objectives clearly and neatly drawn in on the maps: first the Green Line, then the Brown Line, on to the Blue Line and finally crossing the Red Line to victory. Yet it was impossible to tell where these map lines fell on the real terrain. This sense of dislocation was made worse for the 3rd Battalion because of a tactical manoeuvre. Boy Brooke deployed his men too far to the right, intending that the Germans, expecting an attack in a straight line, would miss with their initial artillery strike. At 6 a.m. the British artillery opened up, the German guns replying within seconds. To the great satisfaction of Brooke and Lyttelton, the shells rained down on their former position, missing their new position completely. The disadvantage of the move, however, was that the 3rd Battalion had to make a dog-leg to the left once the attack had started. At 6.20 a.m. they went over the top.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The advance was chaotic. Because the front was so narrow, both the 2nd Battalion and their next-door neighbours, the 3rd Battalion, were supposed to follow battalions of the Coldstream Guards into the attack. Within yards they had both lost all sense of direction. The three battalions of Coldstream Guards lurched off to the left. It was thus very difficult for the Grenadiers to fix their own position. They then discovered that the Germans had created an undetected forward skirmish line that, although it was completely outnumbered, ‘fought with the utmost bravery’. The 2nd Battalion found themselves caught in a ‘German barrage of huge shells bursting at the appalling rate of one a second, [they] were shooting up showers of mud in every direction and the noise was deafening. All this in addition to fierce rifle fire, which came from the right rear.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The German skirmishers succeeded in slowing down and breaking up the British formation before they were overwhelmed. Lyttelton and Brooke ‘flushed two or three Huns from a shell hole, who ran back. They did not get far.’ ‘I have,’ wrote Lyttelton after the battle, ‘only a blurred image of slaughter. I saw about ten Germans writhing like trout in a creel at the bottom of a shell hole and our fellows firing at them from the hip. One or two red bayonets.’

Macmillan was wounded in the knee as they tried to clear these lines. He kept going. Although the battalion passed through the barrage, it immediately ‘came under machine-gun fire from the left front and rifle fire from the right rear. Instead of finding itself…in rear of Coldstream, it was suddenly confronted by a trench full of enemy. This was the first objective, which the men naturally imagined had been taken by the Coldstream.’ They were deployed in artillery formation instead of in line, marching forward under the impression that two battalions of Coldstream Guards were in front of them. To approach the trench with any prospect of success, ‘it was necessary to deploy into line, and in doing this they lost very heavily’. During this manoeuvre Macmillan was shot in the left buttock.

(#litres_trial_promo) It was a severe wound: he rolled into a shell hole and dosed himself with morphine.

Crookshank was equally unlucky. His Lewis guns were doing good work.

(#litres_trial_promo) At about 7 a.m. he was just getting up to push forward once more when a high-explosive shell burst about eight yards in front of him. ‘I felt,’ he later remembered, ‘a great knock in the stomach and saw a stream of blood and gently subsided into a shell hole.’ He was in a perilous position: the shallow shell hole did not provide good cover. If any more shells landed near by he would be sure to be killed. He was saved by his orderly, who crawled to another shell hole and found a corporal, wounded in the head but fit enough to help. Between them the orderly and the corporal managed to carry Crookshank to a better hole, ‘where there were rather fewer shells dropping’. Like Macmillan Crookshank dosed himself with morphine and he and the corporal lay in their waterproof sheets. His orderly went back towards the British lines for help. They lay there for about an hour before the stretcher bearers arrived to evacuate them. Crookshank was conscious but mutilated: the shell had castrated him. Eventually he was taken back towards Ginchy. It was a nightmarish journey.

(#litres_trial_promo) Macmillan’s evacuation had been equally nightmarish. He crawled until he was rescued and had no medical attention for hours. Even when he was picked up by medical orderlies, heavy shelling forced him to abandon his stretcher and scuttle back towards safety.

(#litres_trial_promo) Although they had each escaped death by a fraction and reached field hospitals without being hit again, both were horribly wounded.

Although it was no longer of much interest to either Macmillan or Crookshank, the whole Guards Division was also in deep trouble. On its right the 6th Division had made no progress whatsoever. The tanks over which Churchill had rhapsodized to a sceptical Lyttelton a year before made no impression on their first day of battle. As a result the Guards’ right flank was exposed to a German strongpoint called ‘the Quadrilateral’ that poured fire into it. Their own formation was breaking up under a combination of German fire and the lack of any clear features in the terrain. There were no longer Grenadiers, Coldstreamers, Scots or Irish; they were mixed up together. Small units of men led by charismatic leaders were engaged increasingly in freelance actions. Lyttelton was one such freelancer. Spotting that a gap was opening up between the Coldstream Guards, who were veering to the left, and the Grenadiers, who were trying to shore up the right, he led about a hundred men forward to try and plug their front. His party of Grenadiers caught up with the Coldstreamers, but instead of repairing the front they were simply dragged along by the Scottish regiment, losing contact with their own battalion.