![Rollo's Philosophy. [Air]](https://litportal.ru/covers_330/36364270.jpg)

Rollo's Philosophy. [Air]

When he got ready, he went down into the yard, and found that Jonas had got the horse harnessed, and everything prepared. There was a little bag of oats in the back part of the wagon, and also a tin pail, with a cover, which contained a luncheon. Jonas fastened the horse to a post, and said,—

"Now, Rollo, we'll go in and get some breakfast."

"I thought that luncheon was for breakfast," said Rollo.

"No," said Jonas, "that is for dinner."

"Shall we be gone all the day?" said Rollo.

"We may be gone till after dinner," said Jonas, "and so I thought I would be sure."

The two boys went into the house, and there they found that Dorothy had got some breakfast ready for them upon the kitchen table. After eating their breakfast, they got into the wagon, and set out. Jonas first put in a large umbrella. Just as they were driving out of the yard, the first beams of the morning sun shone in under the branches of a great tree in the yard, and brightened up the tips of the horses' ears and the boys' faces. At the same time, a rude gust of wind came around the corners of the house, and slammed to the gate of the front yard.

"It's going to be pleasant," said Rollo; "the sun is coming out."

"I'm not very sure of that," said Jonas; "the wind is rising."

"We start just at sunrise," said Rollo.

"Yes," replied Jonas, "the sun always rises at six o'clock at this time of the year."

The boys rode along for about three hours, before they came to the carpenter's. They were obliged to travel very slow, for the roads were not good. It is true that the snow was all gone, and the frost was nearly out of the ground; but there were many deep ruts, and in some places it was muddy. The sun went into a cloud soon after they set out, and it continued overcast all the morning. There was some wind too, but, as it was behind them, and as the road lay through woods and among sheltered hills, they did not observe it much. Jonas said that there was a storm coming on, but he thought it was coming slowly.

They arrived at length at the pond. There was a little village there, upon the shore of the pond. The reason why there happened to be a village there, was this: A stream of water, which came down from among the mountains, emptied into the pond here, and, very near where it emptied, it fell over a ledge of rocks, making a waterfall, where the people had built some mills. Now, where there are mills, there must generally be a blacksmith's shop, to mend the iron work when it gets broken, and to repair tools. There is often a tavern, also, for the people who come to the mills; and then there is generally a store or two; for wherever people have to come together, for any business, there is a good place to open a store, to sell them what they want to buy. Thus there was a little village about these mills, which was generally called the Mill village.

Jonas inquired where the carpenter lived, and then drove directly to his house. He found that he was not at home. He had gone across the pond, to mend a bridge, which had been in part carried away by the floods made when the snow went off. Rollo sat in the wagon in the yard by the side of the carpenter's house, while Jonas stood at the door, making inquiries and getting this information.

"If you want to see him very much," said the carpenter's wife, "I presume you can get a boat down in the village, and go across the pond."

"How far is he from the other side of the pond?"

"O, close by the upper landing," said she; "not a quarter of a mile from the shore, right up the road."

Jonas thanked the woman for her information, and got into the wagon.

"Let us get a boat and go over, Jonas," said Rollo, as they were turning the wagon round.

"I should," said Jonas, "if there was not such a threatening of a storm."

"It does not blow much," said Rollo.

"No," said Jonas, "not much now, but the wind may rise before we get back. However, we'll go and see if we can get a boat."

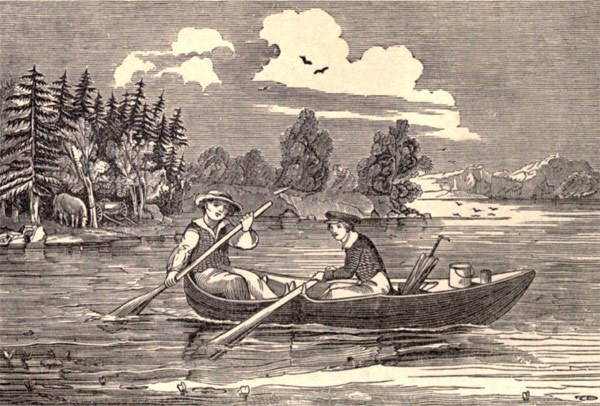

"And very soon they were gliding smoothly along out of the cove."—Page 167.

After some inquiry, they found a boat, at a little distance out of the village, in a sort of cove, where there was a fine, sandy beach. The boat was of very good size, and it had in it two oars and a paddle. Jonas looked out upon the water, and up to the sky, and he listened to hear the moaning of the wind upon the tops of the trees. He wanted very much to persevere in his effort to find the carpenter; but then, on the other hand, he was not sure that it was quite safe to take Rollo out upon the water at such a time. He sat upon a log upon the shore a few minutes, and seemed lost in thought.

At last he said,—

"Well, Rollo, I believe we'll go. The worst that will happen will be, that you may get frightened a little. We can't get hurt."

"Why can't we get hurt?" said Rollo.

"Why, even if it comes on to blow hard, it will probably be a steady gale, and I can run before it, if I can't do anything else. And there can't be much of a sea in this pond."

Rollo did not know what Jonas meant by much of a sea in the pond; but, as Jonas immediately went to work taking the horse out of the wagon, Rollo did not ask any questions. The boys unharnessed the horse, for Jonas said he would stand easier out of harness, and they might be gone more than an hour. They fastened him then to a tree, and poured the oats down before him upon the ground. Then Jonas helped Rollo into the boat, and put in the tin pail containing their luncheon, and also the umbrella; though he said he did not think it would rain before they got back. Then he shoved off the boat, and jumped in himself; and very soon they were gliding smoothly along out of the cove.

Rollo wanted to row; and so Jonas let him take one oar, while he himself sat in the stern with the paddle. Rollo soon learned the proper motion, so that his efforts assisted considerably in propelling the boat. They found, when they were out at a little distance upon the water, that the wind blew much harder than Rollo had expected.

"Jonas," said he, "the wind blows more here than it did upon the shore."

"No," said Jonas, "only we feel it more here than when we were under the lee of the land."

"What do you mean by the lee of the land?" said Rollo.

"I mean the shelter of it," replied Jonas. "Whenever a ship at sea is sheltered by anything, they say the ship is under its lee."

The boys went on, Rollo rowing, and Jonas paddling behind, until at length Rollo got tired. Jonas then told him to spread the umbrella, and hold it up for a sail. Rollo did so. The wind was blowing pretty nearly in the direction in which they were going, and, by its impulse upon the umbrella, it caused it to pull very hard. Rollo rested the middle of the handle of the umbrella upon his shoulder, holding the crook in his hand, turning it in such a position as to present the open part of the umbrella fairly to the wind. Jonas continued to paddle, and so they went on very prosperously until they had got two thirds across the pond, when Jonas ordered Rollo to take in sail.

"Why," said Rollo, "we have not got across yet."

"No," replied Jonas, "but the wind is taking us out of our course."

Rollo drew down the umbrella, and looked around. They were still at a considerable distance from the shore. Jonas extended his paddle out into the water as far as he could reach, and then drew it in towards him with several quick and strong strokes, as if he were endeavoring to pull the stern of the boat, in which he was sitting, round.

"What are you doing so for?" said Rollo.

"I am trying to bring her up into the wind," replied Jonas.

"What is that for?" asked Rollo.

"Why, we've drifted to leeward," said Jonas, "and I must bring her up; for we want to land around behind that point on the starboard bow."

Rollo did not understand Jonas's technical language very well. He particularly did not know what Jonas meant by bringing her up, for it seemed to him that the pond was perfectly level, so that there was no up or down either way. He did not know that, in sea language, against the wind was always up, and with the wind, down.

Jonas found it hard to bring the boat up into the wind. The waves had begun to be pretty large, and they beat against the bows of the boat, and some of the water dashed over upon Rollo. The wind blew quite heavily, too; and now that they had changed their direction so as to bring the wind upon their side, it embarrassed, if it did not absolutely retard their progress. Some drops of rain also began to fall.

However, by hard and persevering exertion, Jonas at length succeeded in urging the boat forward until he began to draw nigh to the point of land; and soon afterwards they came under the shelter of it, where the water was smooth, and the air comparatively still. Here Rollo put in his oar again, and they passed along close under a high shore, for some distance, until they came to the landing. Here they fastened the boat, and then began to walk along up the road.

The road lay through the woods, and among hills, so that it was sheltered; and the only indications of the wind which the boys noticed, was a distant roaring sound among the forests. They came at length to the bridge, where they found several workmen busily engaged in laying abutments of stone, but the carpenter himself was not there. The men told Jonas that he had gone about half a mile away, on a by-road, to select and cut some timber to be used in the construction of the bridge.

"How long will he be gone?" asked Jonas.

"He will be gone two or three hours," said a man with a stone hammer in his hand.

"What shall we do now?" asked Rollo, addressing Jonas, after a short pause.

"Keep on until we find him," replied Jonas. "But you may stay here and see them build the bridge, while I go after the carpenter."

Accordingly Jonas went on, leaving Rollo seated upon a bank watching the work. In about three quarters of an hour, he returned; and then he and Rollo went back to the boat. The wind had all this time continued to increase, though they were so much sheltered, that they did not notice it much.

Jonas, however, observed that some light, scudding clouds were flying across the sky, very low, being apparently far beneath the other clouds. When they reached the boat, Rollo proposed that they should stop and eat some luncheon; but Jonas said that he should eat his with a better appetite on the other side of the pond. So he hastened Rollo into the boat, and, talking his station in the stern, he began to ply his paddle with all his force, running the boat along under the shelter of the high shore.

"There isn't much wind, Jonas," said Rollo.

"We can tell better when we come round the point," replied Jonas.

Rollo observed that Jonas looked a little anxious, and he also seemed to be exerting himself so much in the long, steady strokes of his paddle, that it appeared to be rather an interruption to him to hear and answer questions. Rollo therefore did not talk. He found, however, as he drew near the point, that the waves were running by it, with great speed and force, down the pond. As the boat shot out from the shelter of the point into this place of exposure, the storm struck them suddenly, with a blast which swept the bows of the boat at once round out of her course, and dashed the spray from the waves all over Rollo's face and shoulders. It was with great difficulty that Jonas could bring the boat to the wind again.

He succeeded, however, at length, and they went on, for some time, pitching and tossing, through the waves,—the wind pressing so hard upon the boat that it was very difficult for Jonas to make any headway. The wind had changed its direction, so that it blew now almost exactly across their course; and it required great exertion for Jonas to prevent being blown away down the pond, out of his track altogether.

In the mean time, the wind rather increased than diminished; and the water dashed in so much over the bows that Rollo had to dip it up with the cover of the tin pail, and pour it out over the side of the boat into the pond again. They were going on in this way, both toiling very laboriously, when suddenly they began to hear a sound like distant thunder, somewhat louder than the ordinary roaring of the wind. They both looked towards the shore in the direction from which the sound came. On the declivity of a range of hills covered with forests they saw an unusual commotion among the trees. The tops were bowed down with great force; the branches were broken off, and Jonas thought that he could see fragments of them flying in the air; and presently, farther down, he observed several tall pines bending over, and then sinking down till they disappeared.

"What is it?" said Rollo.

"A squall," said Jonas,—"and coming down directly upon us."

"What shall we do?" asked Rollo.

"Put the boat before the wind," replied Jonas, "and let her run: we must go where the squall carries us."

Jonas immediately began to pull the stern of the boat around with his paddle, so as to turn the head of it away from the quarter which the wind was blowing from; and then the wind drove the boat along very rapidly over the waves, which curled and foamed on each side, driving onward with great fury. When they looked around behind them, they saw that the pond, which was of a very dark color, though spotted with the white tips of the waves all over its surface, was almost black for a large space in the direction from which the squall was coming. It advanced with great rapidity, and at last struck the boat with a noise like thunder. The froth and foam flew over the surface of the water like tufts of cotton, and the boat seemed to fly along the water with almost as much speed as they; and the roaring of the winds and waves was so loud that Rollo had great difficulty in making Jonas hear what he had to say. After a few minutes, the violence of the wind somewhat abated; but it still blew a steady and furious gale, so that Jonas had to keep his boat directly before it. Thus they were driven on, wherever the wind chose to carry them, for more than half an hour.

Then they began to draw near the land, far, however, very far from the place where they had intended to go. Rollo observed that Jonas was looking out very eagerly towards the shore, and he asked him what he was looking for.

"Why, here we are," said Jonas, "on a lee shore, and I am looking out for a place to land."

Rollo looked, and saw that the waves were tumbling with great violence upon the rocks and gravelly beaches which lined the shore, and he was afraid that the boat would get dashed to pieces upon them. Jonas, however, observed a large tree, which originally stood upon the bank, but which had fallen over, and now lay with its top partly submerged. He thought that this might afford him some shelter, and so he made great exertions to guide the boat so as to bring it in to the shore around behind this tree. By means of great efforts he succeeded; and so he and Rollo both escaped safe to land.

The boys did not get home until late that night, for they were thrown upon the shore nearly two miles from the Mill village, and of course they had that distance to walk. Jonas was detained a little there, too, in making arrangements to send a boy for the boat after the storm had subsided. When they got home, Rollo's father said that he was sorry for their fatigues and exposures, but he was very glad that Jonas had persevered and found the carpenter; for the high wind had blown down the back chimney and broken the roof over the kitchen, and it was very necessary to have it repaired immediately.

QUESTIONS

What is momentum? Has air momentum, when it is in motion, as well as water? At what time in the spring of the year does the sun rise at six o'clock? What did Rollo think was the prospect in respect to the weather? What did Jonas think? What is meant by being under the lee of a shore? What is a squall? What indications did Jonas observe of the approach of the squall? What course did he pursue in order to avoid the danger of it?

CHAPTER XII.

AIR AT REST

A few days after the adventure described in the preceding chapter, Rollo heard his father proposing to his mother that they should take a walk the next morning before breakfast. Rollo wanted to go too. His father said that they should be very glad to have his company; and he promised to wake him in season.

Rollo felt rather sleepy, when his father called him the next morning; but he jumped up and dressed himself, and was ready first of all. It was a cool, but a very pleasant morning. The sun was just coming up. The ground in the path before the door was frozen a little, and the air seemed very still.

When Rollo's mother came out to the door, she said,—

"Well, husband, which way shall we go?"

"Up on the rocks," said Rollo; "let's go up on the rocks, mother. It will be beautiful there this morning."

"Well," replied his mother; "we'll go up on the rocks."

The place which Rollo called the rocks, was the summit of a rocky hill, which had a grassy slope upon one side, by which they could ascend, and a precipice of ragged rocks upon the other. There was a very pleasant prospect from the top of the rocks.

As they walked along, Rollo said that it was very different weather that still morning, from what it was the day that he and Jonas were out upon the pond.

"Yes," said his father, "you had an opportunity to see the effects of air in motion then."

"And now air at rest," replied Rollo.

"Pretty nearly," said his father.

"Yes, sir, entirely," said Rollo; "there is no wind at all, this morning: hold up your hand, and you can feel."

So Rollo stopped a moment upon the grass, and held up his hand to see whether there was any wind.

"I know there is not any wind that you can perceive in that way," said his father.

"How can we perceive it, then?" said Rollo.

"I'll tell you," replied his father, "when we get to the top of the hill."

They reached the top of the hill soon after this, and sat down upon a smooth stone. There was a very wide prospect spread out before them,—fields, forests, hamlets, streams,—and here and there, scattered over the landscape, a little patch of snow. The sun was just up, and the whole scene was very bright and beautiful.

"Now, father," said Rollo, "tell me how you know that there is any wind at all."

"I did not say that there was any wind. I said motion of the air."

"Why, father," replied Rollo, "I thought that wind was motion of the air."

"So it is," said his father; "but all motion of the air is not wind. Wind is a current of air, that is, a progressive motion;—and in fact, there is, this morning, a slight current from the westward."

"How can you tell, father?" asked Rollo.

"By the smokes from the chimneys; don't you see that they all lean a little from the west towards the east?"

"Not but a little, father;—and there's one, from that red house, which goes up exactly straight."

"Yes," said his father, "there is one; but, in general, the columns of smoke lean; which is proof that there is a gentle current of air to the eastward."

"Westward, you said, father," rejoined Rollo.

"Yes, from the westward, but to the eastward.

"That is what is called a progressive motion," continued Rollo's father; "that is, the whole body of air makes progress; it advances from west to east. But there is another kind of motion, called a vibratory motion."

"What kind of a motion is that, father?" asked Rollo.

"It is a very hard kind to describe, at any rate," said his father. "It is a kind of quivering, which begins in one place and spreads in every direction. Don't you hear a kind of a thumping sound?"

"Yes," said Rollo, "a great way off; what is it?"

"Look over across the pond there," said his father; "don't you see that man cutting wood?"

"Yes," said Rollo; "that's what makes the noise.—No, father," he continued, after a moment's pause, "that's not it. Look, father, and you'll see that the thumping sound comes when his axe is lifted up."

They all looked, and found that it was as Rollo had said. The strokes of the axe kept time, pretty well, with the sound of blows, which they heard, only the sounds did not correspond with the descent of the axe. When the axe appeared to strike the wood, they did not hear any sound, but they did hear one every time the axe was lifted up.

"So, you see," said Rollo, "it is not that man that we hear. There must be some other man cutting wood."

"We will wait a minute," said his father, "until he gets the log cut off, and then he will stop cutting; and we will see whether we cease to hear the sound."

So they sat still, and watched the man for a minute. Presently he stopped cutting,—and, to Rollo's great surprise, the sound stopped too.

"That's strange," said Rollo.

In a moment more, the man had rolled the log over, and commenced cutting upon the other side; and in an instant after he began to cut, Rollo began to hear the sound of strokes again.

"Yes," said Rollo, "it must be his cutting that we hear; but it is very strange that he makes a noise when he lifts up his axe, and no noise when it goes down."

"I'll tell you how it is," said his father. "He makes the noise when his axe goes down; but, then, it takes some little time for the sound to get here; and by the time the sound gets here, his axe is up."

"O," said Rollo, "is that it?"

"Yes," replied his father, "that is it."

Rollo watched the motion of the axe several minutes longer in silence, and then his attention was attracted by the singing of a bird upon a tree in his father's garden, at a short distance below him.

Pretty soon, however, his mother said that it was time for her to return; and they all, accordingly, arose from their seats, and rambled along together a short distance upon the brow of the hill, but towards home.

"Then the sound moves along through the air," said Rollo, "from the man to us."

"Yes," said his father; "that is, there is a vibratory motion of the air,—a kind of quivering,—which begins where the man is, and spreads all around in every direction, until it reaches us. But there is no progressive motion; that is, none of the air itself, where the man is at work, leaves him, and comes to us."

"But, husband," said Rollo's mother, "I don't see how anything can come from where the man is, to us, unless it is the air itself."

"It is rather hard to understand," said his father. "But I can make an experiment with a string, when we get home, that will show you something about it."

They rambled about among the rocks for a short time longer, and then they descended by a steep and crooked path, in a different place from where they had ascended. When they had got nearly home, Rollo said that he would run forward and get his father's ball of twine and bring it out; and so have it all ready for the experiment.

Accordingly, when Rollo's father and mother arrived at the front door, they found Rollo ready there with a small ball of twine in his hand, about as large as an apple.

"Now, Rollo," said his father, "you may take hold of the end of the twine, and walk along out into the street, while I hold the ball, and let the string unwind."

Rollo did so. He drew out a long piece of twine, as long as the whole front of the house, and then he stopped to ask his father if that was enough.

"No," said his father; "walk along."

So Rollo walked on for some distance farther, until, at last, the ball was entirely unwound. Rollo had one end of it, and was standing at some distance down the road, while his father, with the other end, stood at the gate of the front yard. The middle of the string hung down pretty near to the ground.

"Draw tight, Rollo," said his father.

So Rollo pulled a little harder, and by that means drew the line straighter.

"Now," said his father, "walk along slowly."

So Rollo walked along, drawing the end of the line with him. His father followed with the other end. Thus they advanced several steps along the side of the road.