По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

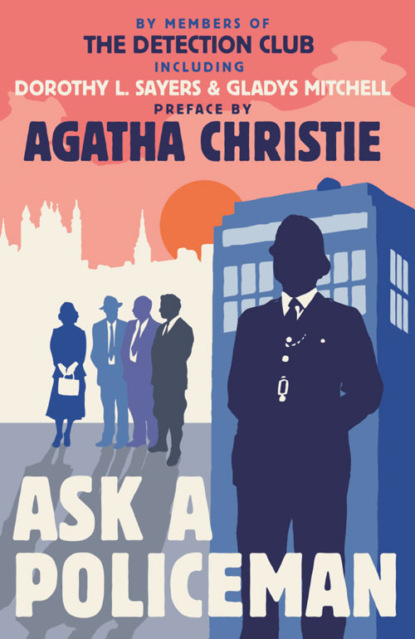

Ask a Policeman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Shawford cleared his throat. “Yes, sir. It was lying on Mr. Littleton’s desk.”

Sir Philip looked speculatively at the designs upon his blotting-paper. “I wonder if it is there now?” he said gently. “I think, Hampton, that it would be as well if you rang up the Yard and asked them to look.”

The Commissioner was about to leave the room, when Shawford spoke again. “I don’t think it will be there now, sir,” he said timidly.

“Don’t you, Chief Constable? And what makes you think that?”

“Well, sir, while I was talking to Mr. Littleton this morning, he picked it up and put it in his pocket. He said something about taking it round to a gunsmith for expert opinion, sir.”

Sir Philip sighed, and leaned back in his chair. “It is extraordinary how difficult it is to elucidate the truth,” he said wearily. “I might surely have been told this fact without the necessity for cross-examination. I begin to feel that Comstock’s attack on the police was not without some justification. I shall expect you, Hampton, to take some action in regard to this want of frankness.”

Fortunately for the Commissioner, his reply was interrupted by the buzzing of the house telephone. Sir Philip picked up the instrument and listened. “Yes, certainly, Anderson,” he said. “A special edition, you say? Oh, I know how they got hold of it. The enterprising Mr. Mills gave them the information over the private telephone from Hursley Lodge. Yes, bring it in, by all means.”

Anderson came in, bearing a special edition of the Evening Clarion, which he handed to Sir Philip. Across the whole width of the front page were the glaring headlines:

MURDER OF LORD COMSTOCK.

WHAT DO THE POLICE KNOW?

Sir Philip glanced through the heavily-leaded letter-press. It contained a vivid account of the events of the morning, obviously derived from Mills’ message. Following this was a special article by “Our well-known Crime Expert,” who was obviously in his element.

“In spite of the fact that one of the Assistant Commissioners of Metropolitan Police, the official who is at the head of our ludicrously inefficient Criminal Investigation Department, was actually present at Hursley Lodge when the dastardly crime was committed, no arrest has yet been made. The British public, accustomed to repeated failures of a similar kind, may see nothing extraordinary in this. But we venture to ask the question, what was the Assistant Commissioner doing at Hursley Lodge? We have authority for stating that his visit was not by appointment with Lord Comstock, and that, in fact, his appearance was entirely unexpected. This visit may have been made with perfectly innocent intentions. But once more we call upon the Home Secretary to insist upon a thorough investigation of the circumstances, and that by some independent body. The Criminal Investigation Department is clearly prejudiced, since its chief official must appear as an actor in the drama. Only the most impartial investigation can be relied upon to solve the mystery of this dastardly outrage.”

And so on, to the extent of a couple of columns or more.

Sir Philip’s expression did not betray his thoughts-as he handed the paper to the Commissioner. “Well, Hampton, what do you make of that?” he asked.

The Commissioner ran his eye through the article, and frowned. “It seems that Comstock’s stunts live after him,” he replied.

“Stunt or no stunt it seems to me that Littleton’s visit to Hursley Lodge will want a lot of explanation,” said Sir Philip gravely. “As this fellow asks, what was he doing there? We know that he bitterly resented Comstock’s attack on Scotland Yard. Several other details have been revealed, which place his actions in none too favourable a light. And the grim fact remains that Comstock has been murdered.”

There was no mistaking the significance of the Home Secretary’s words. But the Commissioner, bitterly annoyed as he was with Littleton’s account of his actions, was not prepared to acquiesce tamely in his guilt. Not that he considered it impossible. Littleton was notoriously headstrong. It was certain that he and Comstock could not have met, even for a moment, without a furious altercation arising immediately. This would undoubtedly have led to personal violence if the characters of the two men were considered. Littleton would not have shot Comstock in cold blood. But if Comstock had threatened him with the pistol found on his desk—

No; the Commissioner’s reluctance to admit the possibility of Littleton’s guilt was not based upon conviction. It was due to his appreciation of the scandal which must ensue if such a thing were suggested. It might well be argued that if an Assistant Commissioner of Police were capable of murder, Comstock’s attacks upon that force were fully justified. For the honour of the Department of which he had charge, it was essential that no breath of official suspicion should cloud for a moment the reputation of his subordinate.

“If you will forgive my saying so, sir, it is ridiculous to suppose that Littleton can have had anything to do with the crime,” he said stiffly. “I am well aware that he is impulsive to a fault, and that he would go to almost any lengths to defend his colleagues from outside attack. But nobody who knew him well would believe for a moment that he would condescend to murder. Chief Constable Shawford, who for years has worked in close association with him, will bear me out in that.”

“That I will, sir!” exclaimed Shawford courageously. “I’d sooner suspect myself than Mr. Littleton.”

“The esprit de corps displayed by the officers of your Department is really touching, Compton,” Sir Philip remarked drily. “In vulgar parlance, they’d rather die than give one another away. I am not likely to forget the difficulty which I experienced in extracting the truth about the second pistol. If you insist that Littleton cannot be guilty, what alternative do you suggest?”

“I would point out that Sir Charles Hope-Fairweather’s replies to your questions were scarcely satisfactory,” the Commissioner replied equally.

“Hope-Fairweather! I’ll admit that some politicians are hardly qualified to sit among the angels. But they do not as a rule indulge in personal murder. Besides, why in the world should Hope-Fairweather want to murder Comstock?”

“There must be a good many people who, for various reasons, will rejoice at his death. He was the sort of man who makes private enemies as well as public ones. For instance, his dealings with women were notorious, and in some cases sufficiently scandalous. And Hope-Fairweather had a woman, whose name he refuses to divulge, with him when he went to Hursley Lodge.”

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: