По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

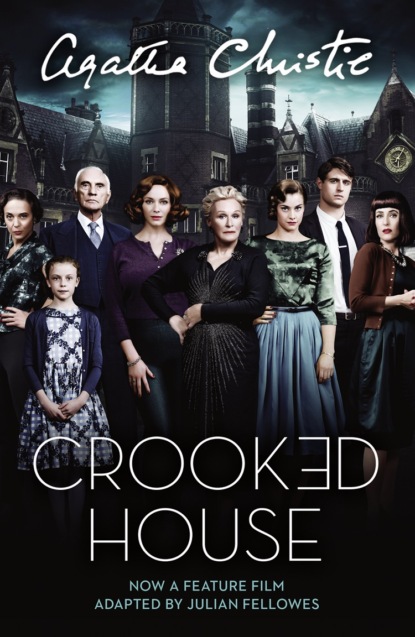

Crooked House

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘A very clear idea. He re-made his will in 1946. My father was not a secretive man. He had a great sense of family. He held a family conclave at which his solicitor was also present and who, at his request, made clear to us the terms of the will. These terms I expect you already know. Mr Gaitskill will doubtless have informed you. Roughly, a sum of a hundred thousand pounds free of duty was left to my stepmother in addition to her already very generous marriage settlement. The residue of his property was divided into three portions, one to myself, one to my brother, and a third in trust for the three grandchildren. The estate is a large one, but the death duties, of course, will be very heavy.’

‘Any bequests to servants or to charity?’

‘No bequests of any kind. The wages paid to servants were increased annually if they remained in his service.’

‘You are not—you will excuse my asking—in actual need of money, Mr Leonides?’

‘Income tax, as you know, is somewhat heavy, Chief Inspector—but my income amply suffices for my needs—and for my wife’s. Moreover, my father frequently made us all very generous gifts, and had any emergency arisen, he would have come to the rescue immediately.’

Philip added coldly and clearly:

‘I can assure you that I had no financial reason for desiring my father’s death, Chief Inspector.’

‘I am very sorry, Mr Leonides, if you think I suggested anything of the kind. But we have to get at all the facts. Now I’m afraid I must ask you some rather delicate questions. They refer to the relations between your father and his wife. Were they on happy terms together?’

‘As far as I know, perfectly.’

‘No quarrels?’

‘I do not think so.’

‘There was a—great disparity in age?’

‘There was.’

‘Did you—excuse me—approve of your father’s second marriage?’

‘My approval was not asked.’

‘That is not an answer, Mr Leonides.’

‘Since you press the point, I will say that I considered the marriage unwise.’

‘Did you remonstrate with your father about it?’

‘When I heard of it, it was an accomplished fact.’

‘Rather a shock to you—eh?’

Philip did not reply.

‘Was there any bad feeling about the matter?’

‘My father was at perfect liberty to do as he pleased.’

‘Your relations with Mrs Leonides have been amicable?’

‘Perfectly.’

‘You are on friendly terms with her?’

‘We very seldom meet.’

Chief Inspector Taverner shifted his ground.

‘Can you tell me something about Mr Laurence Brown?’

‘I’m afraid I can’t. He was engaged by my father.’

‘But he was engaged to teach your children, Mr Leonides.’

‘True. My son was a sufferer from infantile paralysis—fortunately a light case—and it was considered not advisable to send him to a public school. My father suggested that he and my young daughter Josephine should have a private tutor—the choice at the time was rather limited—since the tutor in question must be ineligible for military service. This young man’s credentials were satisfactory, my father and my aunt (who has always looked after the children’s welfare) were satisfied, and I acquiesced. I may add that I have no fault to find with his teaching, which has been conscientious and adequate.’

‘His living quarters are in your father’s part of the house, not here?’

‘There was more room up there.’

‘Have you ever noticed—I am sorry to ask this—any signs of intimacy between Laurence Brown and your stepmother?’

‘I have had no opportunity of observing anything of the kind.’

‘Have you heard any gossip or tittle-tattle on the subject?’

‘I don’t listen to gossip or tittle-tattle, Chief Inspector.’

‘Very creditable,’ said Inspector Taverner. ‘So you’ve seen no evil, heard no evil, and aren’t speaking any evil?’

‘If you like to put it that way, Chief Inspector.’

Inspector Taverner got up.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘thank you very much, Mr Leonides.’

I followed him unobtrusively out of the room.

‘Whew,’ said Taverner, ‘he’s a cold fish!’

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_ab3c0155-eedb-5d39-b85b-7c1b63c1c936)

‘And now,’ said Taverner, ‘we’ll go and have a word with Mrs Philip. Magda West, her stage name is.’

‘Is she any good?’ I asked. ‘I know her name, and I believe I’ve seen her in various shows, but I can’t remember when and where.’

‘She’s one of those Near Successes,’ said Taverner. ‘She’s starred once or twice in the West End, she’s made quite a name for herself in repertory—she plays a lot for the little highbrow theatres and the Sunday clubs. The truth is, I think, she’s been handicapped by not having to earn her living at it. She’s been able to pick and choose, and to go where she likes and occasionally to put up the money and finance a show where she’s fancied a certain part—usually the last part in the world to suit her. Result is, she’s receded a bit into the amateur class rather than the professional. She’s good, mind you, especially in comedy—but managers don’t like her much—they say she’s too independent, and she’s a troublemaker—foments rows and enjoys a bit of mischief-making. I don’t know how much of it is true—but she’s not too popular amongst her fellow artists.’

Sophia came out of the drawing-room and said: ‘My mother is in here, Chief Inspector.’

I followed Taverner into the big drawing-room. For a moment I hardly recognized the woman who sat on the brocaded settee.