По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

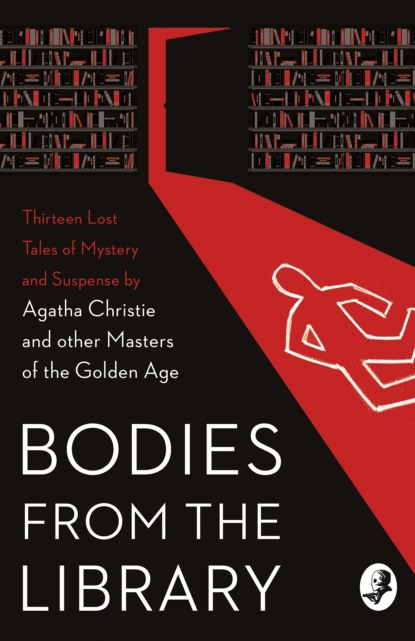

Bodies from the Library: Lost Tales of Mystery and Suspense by Agatha Christie and other Masters of the Golden Age

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

ALICE: He hinted things—about you and me. That’s what he’s got Mr Strangeways for. To spy on us. He’s a detective.

LAURENCE: The swine. That settles it. I’m going to have to talk with Sir James Braithwaite.

ALICE: No. Stop. It’s no good. You don’t understand, Laurence. I don’t mind the things he says. Not now. I’m broken in, I suppose. One gets used to anything, even the misery he’s made of my life. Yes, I’ve forgotten what happiness feels like. But when he talked about my child, it came to me—what sort of life would it have with him for a father? I can put up with his bullying, his meanness, his suspicions: but I won’t let my baby—

LAURENCE: You must leave him, my dear. You must.

ALICE: He’d never let me go … (very flat, speaking half to self) Unless … yes, there is one way … Perhaps I shall leave him … Sooner than he—

(Cough. Footsteps)

GREER: Well, lass, sharpening up your appetite? That’s right. But what’s this? Tears? Well now, this won’t do.

ALICE: It’s nothing, Daddy. I—this baby makes me feel weak and silly. It’s nothing, really.

GREER: Come now, that’s better, take my arm. We’ll go into the saloon. It’s just on dinner-time.

(Footsteps recede. Noises of sea. Then fade into general conversation)

LAURA: Well, that’s what I call a slap-up dinner. I only hope I will be able to keep it inside me. Is it going to be very rough tonight, Captain?

GREER: Don’t you worry, Miss Annesley. Weather reports say we may run into a bit of local fog. Nothing worse than that. She’ll not jump about much till we get into the Bay, and you’ll have your sea-legs by then.

LAURENCE: Well, Strangeways, how’s the—secretarial work going?

NIGEL: O.K., thank you kindly.

JAMES: Mr Strangeways is a confidential secretary, Annesley?

LAURENCE: yes. To be sure. A formidable responsibility—to be the repository of Sir James Braithwaite’s secrets.

(Embarrassed pause)

LAURA: I’m sure it’ll be very nice for Mr Strangeways to have something to do—to keep his mind occupied, I mean. I mean, there are limits to one’s capacity for playing deck-quoits. I say—that reminds me—where are all the sailors, Captain?

GREER: The sailors?

LAURA: Yes. I was on the deck quite a long time before dinner, and I never saw a single one. I thought there’d be dozens of them—polishing the binnacle and letting the bullgine run, and so on.

LAURENCE: Bad luck, Laura. All your beautiful cruise-wear wasted.

GREER: A modern cargo vessel pretty well runs itself, Miss Annesley. You’ll not find seamen on the deck, except when the watches are being changed. We’ve nothing to do but squirt oil into the engine now and then; the rest of the time we spend knitting socks for our nippers.

LAURA: Knitting socks?—He’s pulling my leg, isn’t he, Sir James?

JAMES: The modern seaman certainly has an easy time if it, compared with the man of thirty years ago.

GREER: Aye. All that brass we had to clean. Wherever they could put a bit of brass on those old tramps, they did.

JAMES: —And nowadays he doesn’t know when he’s well off. Better food, more comfortable quarters, overtime pay.

MACLEAN: He’ll have an easy time, maybe—till the ship starts to go down under his feet.

(Another embarrassed pause)

LAURA: Oh but how gruesome you are, Mr Maclean. Have you ever been in a shipwreck? Do tell us all about it.

GREER: Well, if you ladies and gentlemen will excuse me, I’ll just see if the shore agent has got anything to tell me. He rings me up at 8.30. You see, Miss Annesley, I just put on these headphones, and turn this switch, and—

(Pause. Faintly we hear, as over the radio telephone—)

VOICE: ‘James Braithwaite’. ‘James Braithwaite’. ‘James Braithwaite’. Cullercoats radio calling. Cullercoats radio calling. Cullercoats radio calling the ‘James Braithwaite’. Over to you.

GREER: ‘James Braithwaite’ answering. ‘James Braithwaite’ answering Cullercoats radio. Over to you.

(Sound of switch being put over. The others begin to talk quietly, so that we now only hear the captain’s end of the conversation. His sudden excitement, however, soon stops their talk.)

GREER: Hello, Tom … How’s the wife keeping?… That’s fine. Anything for me? What’s that? (Long pause: the passengers’ talk dies out: we hear squeaky unintelligible noises through the radio telephone.) Well, that’s a nice thing. Why can’t they keep a better look-out?… Eh?… And what am I supposed to do about it: I haven’t got a padded cell on my ship, have I?… Oh, get out with you!… Oh, he is, is he? Yes, I see. I’ll take action. Yes, I’ll take action. Goodbye, Tom.

(Pause. They are expecting the captain to speak)

JAMES: Well, Greer, what is it? What was all that about?

GREER: I’ve had a rather disagreeable message … A warning, you might say.

ALICE: ‘Warning’, Daddy? What—?

GREER: it seems a chap escaped from that lunatic asylum at Newcastle last night.

LAURA: Oo-er. Is he swimming after the ship?

GREER: They’ve just had a report that someone answering to this chap’s description was seen hanging round the docks early this morning, near the ‘James Braithwaite’. A big chap, with a limp—a sort of shuffling walk—is the way they describe it. An ex-seaman, he is.

JAMES: (sharply) Well, what about it?

GREER: Well, it seems this chap has delusions. He’s what they call a homocidal maniac.

ALICE: Oh!

GREER: Now don’t upset yourself, lass. No reason to suppose the fellow got aboard. We’ll have the ship searched, just to make sure he’s not here. Mr Maclean, take a search-party if you please, and go right over her.

MACLEAN: Very good, sir.

(Gets up: sound of door closing)

GREER: Lucky we’ve got a detective on board. May come in useful.

LAURA: Detective? Well, I’ll say this is a surprise packet. First we get a loony, then a detective—what’ll you give us next?—the Grand Lama of Tibet? Where is this mysterious detective?