По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

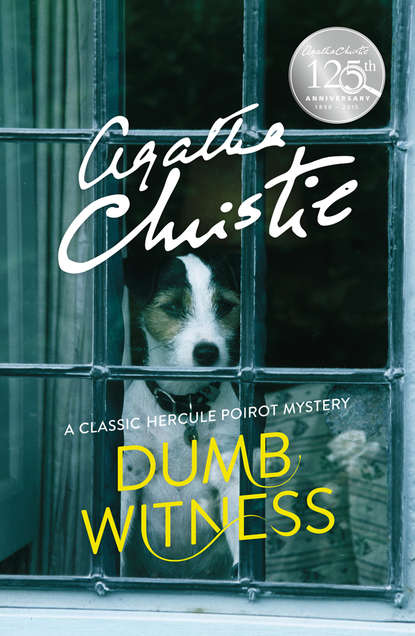

Dumb Witness

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Originally, yes, sir, but that was before my time. There was only Miss Agnes and Miss Emily when I came and Miss Agnes died soon afterwards. She was the youngest of the family. It seemed odd she should go before her sister.’

‘I suppose she was not so strong as her sister?’

‘No, sir, it’s odd that. My Miss Arundell, Miss Emily, she was always the delicate one. She’d had a lot to do with doctors all her life. Miss Agnes was always strong and robust and yet she went first and Miss Emily who’d been delicate from a child outlived all the family. Very odd the way things happen.’

‘Astonishing how often that is the case.’

Poirot plunged into (I feel sure) a wholly mendacious story of an invalid uncle which I will not trouble to repeat here. It suffices to say that it had its effect. Discussions of death and such matters do more to unlock the human tongue than any other subject. Poirot was in a position to ask questions that would have been regarded with suspicious hostility twenty minutes earlier.

‘Was Miss Arundell’s illness a long and painful one?’

‘No, I wouldn’t say that, sir. She’d been ailing, if you know what I mean, for a long time—ever since two winters before. Very bad she was then—this here jaundice. Yellow in the face they go and the whites of their eyes—’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: