По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

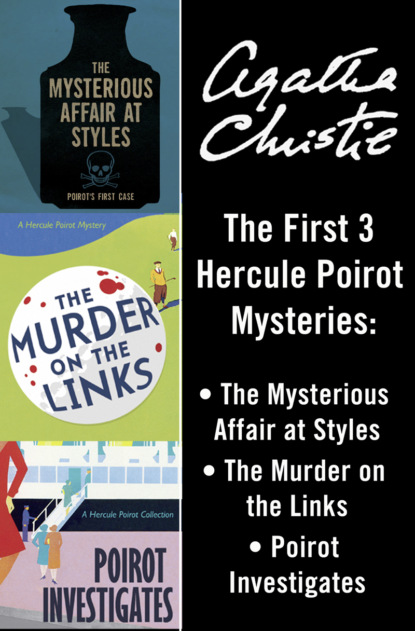

Hercule Poirot 3-Book Collection 1: The Mysterious Affair at Styles, The Murder on the Links, Poirot Investigates

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I had been invalided home from the Front; and, after spending some months in a rather depressing Convalescent Home, was given a month’s sick leave. Having no near relations or friends, I was trying to make up my mind what to do, when I ran across John Cavendish. I had seen very little of him for some years. Indeed, I had never known him particularly well. He was a good fifteen years my senior, for one thing, though he hardly looked his forty-five years. As a boy, though, I had often stayed at Styles, his mother’s place in Essex.

We had a good yarn about old times, and it ended in his inviting me down to Styles to spend my leave there.

‘The mater will be delighted to see you again—after all those years,’ he added.

‘Your mother keeps well?’ I asked.

‘Oh, yes. I suppose you know that she has married again?’

I am afraid I showed my surprise rather plainly. Mrs Cavendish, who had married John’s father when he was a widower with two sons, had been a handsome woman of middle-age as I remembered her. She certainly could not be a day less than seventy now. I recalled her as an energetic, autocratic personality, somewhat inclined to charitable and social notoriety, with a fondness for opening bazaars and playing the Lady Bountiful. She was a most generous woman, and possessed a considerable fortune of her own.

Their country-place, Styles Court, had been purchased by Mr Cavendish early in their married life. He had been completely under his wife’s ascendancy, so much so that, on dying, he left the place to her for her lifetime, as well as the larger part of his income; an arrangement that was distinctly unfair to his two sons. Their stepmother, however, had always been most generous to them; indeed, they were so young at the time of their father’s remarriage that they always thought of her as their own mother.

Lawrence, the younger, had been a delicate youth. He had qualified as a doctor but early relinquished the profession of medicine, and lived at home while pursuing literary ambitions; though his verses never had any marked success.

John practised for some time as a barrister, but had finally settled down to the more congenial life of a country squire. He had married two years ago, and had taken his wife to live at Styles, though I entertained a shrewd suspicion that he would have preferred his mother to increase his allowance, which would have enabled him to have a home of his own. Mrs Cavendish, however, was a lady who liked to make her own plans, and expected other people to fall in with them, and in this case she certainly had the whip hand, namely: the purse strings.

John noticed my surprise at the news of his mother’s remarriage and smiled rather ruefully.

‘Rotten little bounder too!’ he said savagely. ‘I can tell you, Hastings, it’s making life jolly difficult for us. As for Evie—you remember Evie?’

‘No.’

‘Oh, I suppose she was after your time. She’s the mater’s factotum, companion, Jack of all trades! A great sport—old Evie! Not precisely young and beautiful, but as game as they make them.’

‘You were going to say –’

‘Oh, this fellow! He turned up from nowhere, on the pretext of being a second cousin or something of Evie’s, though she didn’t seem particularly keen to acknowledge the relationship. The fellow is an absolute outsider, anyone can see that. He’s got a great black beard, and wears patent leather boots in all weathers! But the mater cottoned to him at once, took him on as secretary—you know how she’s always running a hundred societies?’

I nodded.

‘Well, of course, the war has turned the hundreds into thousands. No doubt the fellow was very useful to her. But you could have knocked us all down with a feather when, three months ago, she suddenly announced that she and Alfred were engaged! The fellow must be at least twenty years younger than she is! It’s simply bare-faced fortune hunting; but there you are—she is her own mistress, and she’s married him.’

‘It must be a difficult situation for you all.’

‘Difficult! It’s damnable!’

Thus it came about that, three days later, I descended from the train at Styles St Mary, an absurd little station, with no apparent reason for existence, perched up in the midst of green fields and country lanes. John Cavendish was waiting on the platform, and piloted me out to the car.

‘Got a drop or two of petrol still, you see,’ he remarked. ‘Mainly owing to the mater’s activities.’

The village of Styles St Mary was situated about two miles from the little station, and Styles Court lay a mile the other side of it. It was a still, warm day in early July. As one looked out over the flat Essex country, lying so green and peaceful under the afternoon sun, it seemed almost impossible to believe that, not so very far away, a great war was running its appointed course. I felt I had suddenly strayed into another world. As we turned in at the lodge gates, John said:

‘I’m afraid you’ll find it very quiet down here, Hastings.’

‘My dear fellow, that’s just what I want.’

‘Oh, it’s pleasant enough if you want to lead the idle life. I drill with the volunteers twice a week, and lend a hand at the farms. My wife works regularly “on the land”. She is up at five every morning to milk, and keeps at it steadily until lunch-time. It’s a jolly good life taking it all round—if it weren’t for that fellow Alfred Inglethorp!’ He checked the car suddenly, and glanced at his watch. ‘I wonder if we’ve time to pick up Cynthia. No, she’ll have started from the hospital by now.’

‘Cynthia! That’s not your wife?’

‘No, Cynthia is a protégée of my mother’s, the daughter of an old schoolfellow of hers, who married a rascally solicitor. He came a cropper, and the girl was left an orphan and penniless. My mother came to the rescue, and Cynthia has been with us nearly two years now. She works in the Red Cross Hospital at Tadminster, seven miles away.’

As he spoke the last words, we drew up in front of the fine old house. A lady in a stout tweed skirt, who was bending over a flower bed, straightened herself at our approach.

‘Hullo, Evie, here’s our wounded hero! Mr Hastings—Miss Howard.’

Miss Howard shook hands with a hearty, almost painful, grip. I had an impression of very blue eyes in a sunburnt face. She was a pleasant-looking woman of about forty, with a deep voice, almost manly in its stentorian tones, and had a large sensible square body, with feet to match—these last encased in good thick boots. Her conversation, I soon found, was couched in the telegraphic style.

‘Weeds grow like house afire. Can’t keep even with ’em. Shall press you in. Better be careful!’

‘I’m sure I shall be only too delighted to make myself useful,’ I responded.

‘Don’t say it. Never does. Wish you hadn’t later.’

‘You’re a cynic, Evie,’ said John, laughing. ‘Where’s tea today—inside or out?’

‘Out. Too fine a day to be cooped up in the house.’

‘Come on then, you’ve done enough gardening for today. “The labourer is worthy of his hire,” you know. Come and be refreshed.’

‘Well,’ said Miss Howard, drawing off her gardening gloves, ‘I’m inclined to agree with you.’

She led the way round the house to where tea was spread under the shade of a large sycamore.

A figure rose from one of the basket chairs, and came a few steps to meet us.

‘My wife, Hastings,’ said John.

I shall never forget my first sight of Mary Cavendish. Her tall, slender form, outlined against the bright light; the vivid sense of slumbering fire that seemed to find expression only in those wonderful tawny eyes of hers, remarkable eyes, different from any other woman’s that I have ever known; the intense power of stillness she possessed, which nevertheless conveyed the impression of a wild untamed spirit in an exquisitely civilized body—all these things are burnt into my memory. I shall never forget them.

She greeted me with a few words of pleasant welcome in a low clear voice, and I sank into a basket chair feeling distinctly glad that I had accepted John’s invitation. Mrs Cavendish gave me some tea, and her few quiet remarks heightened my first impression of her as a thoroughly fascinating woman. An appreciative listener is always stimulating, and I described, in a humorous manner, certain incidents of my Convalescent Home, in a way which, I flatter myself, greatly amused my hostess. John, of course, good fellow though he is, could hardly be called a brilliant conversationalist.

At that moment a well remembered voice floated through the open french window near at hand:

‘Then you’ll write to the Princess after tea, Alfred? I’ll write to Lady Tadminster for the second day, myself. Or shall we wait until we hear from the Princess? In case of a refusal, Lady Tadminster might open it the first day, and Mrs Crosbie the second. Then there’s the Duchess—about the school fête.’

There was the murmur of a man’s voice, and then Mrs Inglethorp’s rose in reply:

‘Yes, certainly. After tea will do quite well. You are so thoughtful, Alfred dear.’

The french window swung open a little wider, and a handsome white-haired old lady, with a somewhat masterful cast of features, stepped out of it on to the lawn. A man followed her, a suggestion of deference in his manner.

Mrs Inglethorp greeted me with effusion.

‘Why, if it isn’t too delightful to see you again, Mr Hastings, after all these years. Alfred, darling, Mr Hastings—my husband.’

I looked with some curiosity at ‘Alfred darling’. He certainly struck a rather alien note. I did not wonder at John objecting to his beard. It was one of the longest and blackest I have ever seen. He wore gold-rimmed pince-nez, and had a curious impassivity of feature. It struck me that he might look natural on a stage, but was strangely out of place in real life. His voice was rather deep and unctuous. He placed a wooden hand in mine and said: