По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

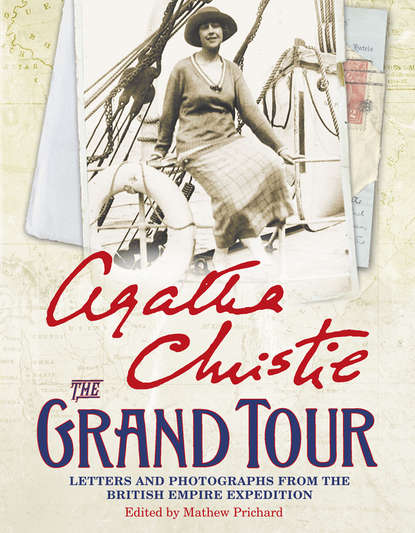

The Grand Tour: Letters and photographs from the British Empire Expedition 1922

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

So, Nima and Archie set off and what follows in this book is a completely spontaneous outpouring of wonder at the different people, scenery and events that unfolded before them as they went. Some of what they saw, such as the Victoria Falls, Table Mountain and Sydney Harbour, are still there, though much developed. Much more poignant to me (for I have visited all three cities) were the pictures of Hobart, Wellington, and particularly Cathedral Square in Christchurch, New Zealand. The first two are completely unrecognizable from the buzzing cities you see today. A simple black-and-white picture overwhelms me with a powerful sense of natural elegance and beauty, and, I confess, with a sense of guilt and regret that progress has meant the destruction of some thing so intrinsically valuable. Christchurch, of course, suffered a devastating earthquake in 2011, but I suspect that if a 1922 resident could see how the city has developed over the intervening decades, he or she would mourn the urban developments almost as poignantly.

One episode which particularly impressed me was Nima’s trip to Coochin Coochin Station to visit the Bells, who (as she said) seemed to own most of the cattle in Australia. With their natural vivacity and energy, the Bells provided a stark contrast to the inhibiting nature of Belcher’s company; but is it entirely my imagination that the freedom, spontaneity and independence displayed by the Bells on their own patch was something that Nima had never experienced before? I suspect, in good times and in bad, she never forgot it. I remember, in the 1950s, meeting Guilford Bell, Frick’s son, who ended up being one of the most innovative and successful architects in Australia, designing some iconic buildings on Sydney Harbour and in Melbourne. I remember him leaving after a weekend with us all and writing in the visitor’s book at Greenway, which desperately needed a lick of paint at the time, ‘Always paint me white!’ I also remember visiting him for dinner in his disarmingly simple (white) house in Melbourne, in which he had decreed that only one picture should be on display in each room. No matter, in the Living Room was one of the most charismatic and glowering landscapes I have ever seen, painted by Russell Drysdale as a gift to Guilford, who had designed a house for him. The Bells, all of them, were an inspiration to Nima. No wonder.

What is one to say about Nima’s photography? Ignoring the basic quality of her equipment (she had her camera stolen in South Africa – in my opinion the replacement was better) – it manages to be amazingly evocative. In browsing through the two albums she left us, I couldn’t help but admire her assiduousness: the camera must never have left her side. Perhaps this is also a figment of my imagination but I found myself thinking that her photography was like her writing in a different medium – spontaneous, direct, but occasionally with a shaft of brilliant artistic talent. The following is a list of subjects which she photographed that particularly impressed me – all quite different yet each evocative in its own way of the time and place it happened: logging in Canada, surfing in Honolulu, the police in Suva, the youngest cotton picker, trains, Susan in Coochin Coochin, and the ‘Bush train’. I will give you no further details – you will enjoy finding them for yourselves.

You would not be surprised to hear that the question I am most often asked about Nima is, ‘Yes, but what was she really like?’ I have spent, over the past month or so, some time reading these letters and looking at these photographs, and asking myself whether, in the light of what they reveal, my standard answers need to be reviewed. My standard answers were that she was a shy, reserved person, who was very reluctant to talk in public, give press interviews, discuss her work or otherwise engage in activity other than writing books. She was never happier than being with her family or close friends; she was a devout person who believed in God (and in evil) and, to me, an inspirational grandmother far more interested in my own likes and dislikes than in promoting or discussing herself. She was, I have always said, the best listener I ever met. I still believe, based on the evidence of the 25 years or so that I knew her well, that all this is true.

But, as I read her account of the Grand Tour, I see glimpses of another Agatha Christie. One with far more confidence in herself publicly than the one I remember. One who sang in public in Coochin Coochin, was very sociable on board ship, and who had the courage to make the decision to go on the tour and leave her daughter for 10 months. A person who, even though it turned out to be the wrong thing to do, took her place directly beside local dignitaries at the lunch table until being told to go back and sit next to her husband. A young woman of 32 who was actually confident in herself, and in her husband, amid constantly changing circumstances and for the most part in the company of total strangers. One suspects, indeed, that Nima and Archie were the glue that held the tour together, particularly in view of Belcher’s unpredictable nature. So I find myself in the presence of a younger Agatha, more confident and assertive than the Nima that I remember – and what do I feel? I feel even more proud of her.

Some three to four years after returning from the tour, as all the world seems to know, Nima had to suffer the death of her mother, and separation and divorce from Archie. As a consequence of these traumatic experiences, she famously got lost, or disappeared, eventually to reappear in Harrogate under another name. It is not appropriate to discuss here the details of this experience, except to say that for most of us the juxtaposition of two of the most disturbing events that can happen to anyone would be life-changing. I am sure Nima was no exception and that a very important part of the confident, carefree wife who accompanied Archie in 1922 was lost forever after the events of1926–27. Fromthenon, despite a very successful second marriage, all her confidence, energy and genius were concentrated on supporting her new husband and, of course, on her work. The days of vivacious Agatha at public gatherings were not to return; but perhaps in the end we were all the benefactors, for in both quantity and quality her work after 1927 was amazing.

From a historical point of view the account of the Grand Tour, both literary and photographic, is a remarkable snapshot of life in the 1920s, nostalgic and curious. For me it is also a glorious vision of a grandmother I never knew, but who I am very glad existed.

I always think that anybody who ventures to write about Agatha Christie should not bypass her work, and Nima would have agreed. I therefore have to tell you that shortly after the British Empire Mission returned home, Nima published The Man in the Brown Suit, an adventure story; and unusually for her, she included a direct portrayal of a real acquaintance – an impersonation of Belcher called Sir Eustace Pedler. Until Belcher objected, he was going to be murdered, but Nima gave him a title (‘he will like that,’ said Archie). As I never reveal the plots of Nima’s stories, all I will say beyond that is that Sir Eustace plays a prominent role! Nima very rarely used real individuals as the basis for her characters, indeed I’m not sure this wasn’t the only instance; and she didn’t really think it worked. Thus, however, were the many varied characters and events of the Grand Tour given fictional representation. Interestingly, there are those who think that Anne Beddingfield has a marked resemblance to the young and adventurous Agatha too…

Finally, I have tried to interfere with the flow and content of the letters as little as possible. We should all remember that the letters were written 90 years ago in a different social era, and inevitably there is also some repetition, as well as occasional inconsistencies in grammar and punctuation. Many of the captions to the photographs are Nima’s own own from her albums.

MATHEW PRICHARD

20 January 2012

PREFACE (#ulink_471ed8ad-080d-5120-96b7-dc2ccc94c5ab)

I had written three books, was happily married, and my heart’s desire was to live in the country.

Both Archie and Patrick Spence – a friend of ours who also worked at Goldstein’s – were getting rather pessimistic about their jobs: the prospects as promised or hinted at did not seem tomaterialise. They were given certain directorships, butthe director ships were always of hazardous companies – sometimes on the brink of bankruptcy. Spence once said, ‘I think these people are a lot of ruddy crooks. All quite legal, you know. Still, I don’t like it, do you?’

Archie said that he thought that some of it was not very reputable. ‘I rather wish,’ he said thoughtfully, ‘I could make a change.’ He liked City life and had an aptitude for it, but as time went on he was less and less keen on his employers.

And then something completely unforeseen came up.

Archie had a friend who had been a master at Clifton – a Major Belcher. Major Belcher was a character. He was a man with terrific powers of bluff. He had, according to his own story, bluffed himself into the position of Controller of Potatoes during the war. How much of Belcher’s stories was invented and how much true, we never knew, but anyway he made a good story of this one. He had been a man of forty or fifty odd when the war broke out, and though he was offered a stay-at-home job in the War Office he did not care for it much. Anyway, when dining with a V.I.P. one night, the conversation fell on potatoes, which were really a great problem in the 1914–18 war. As far as I can remember, they vanished quite soon. At the hospital, I know, we never had them. Whether the shortage was entirely due to Belcher’s control of them I don’t know, but I should not be surprised to hear it.

‘This pompous old fool who was talking to me,’ said Belcher, ‘said the potato position was going to be serious, very serious indeed. I told him that something had to be done about it – too many people messing about. Somebody had got to take the whole thing over – one man to take control. Well, he agreed with me. “But mind you,”’ I said, “he’d have to be paid pretty highly. No good giving a mingy salary to a man and expecting to get one who’s any good – you’ve got to have someone who’s the tops. You ought to give him at least—”’ and here he mentioned a sum of several thousands of pounds. ‘That’s very high,’ said the V.I.P. ‘You’ve got to get a good man,’ said Belcher. ‘Mind you, if you offered it to me, I wouldn’t take it on myself, at that price.’

That was the operative sentence. A few days later Belcher was begged, on his own valuation, to accept such a sum, and control potatoes.

‘What did you know about potatoes?’ I asked him.

‘I didn’t know a thing,’ said Belcher. ‘But I wasn’t going to let on. I mean, you can do anything – you’ve only got to get a man as second-in-command who knows a bit about it, and read it up a bit, and there you are!’ He was a man with a wonderful capacity for impressing people. He had a great belief in his own powers of organisation – and it was sometimes a long time before anyone found out the havoc he was causing. The truth is that there never was a man less able to organise. His idea, like that of many politicians, was first to disrupt the entire industry, or whatever it might be, and having thrown it into chaos, to reassemble it, as Omar Khayyam might have said, ‘nearer to the heart’s desire’. The trouble was that, when it came to reorganising, Belcher was no good. But people seldom discovered that until too late.

At some period of his career he went to New Zealand, where he so impressed the governors of a school with his plans for reorganisation that they rushed to engage him as headmaster. About a year later he was offered an enormous sum of money to give up the job – not because of any disgraceful conduct, but solely because of the muddle he had introduced, the hatred which he aroused in others, and his own pleasure in what he called ‘a forward-looking, up-to-date, progressive administration’. As I say, he was a character. Sometimes you hated him, sometimes you were quite fond of him.

Belcher came to dinner with us one night, being out of the potato job, and explained what he was about to do next. ‘You know this Empire Exhibition we’re having in eighteen months’ time? Well, the thing has got to be properly organised. The Dominions have got to be alerted, to stand on their toes and to co-operate in the whole thing. I’m going on a mission – the British Empire Mission – going round the world, starting in January.’ He went on to detail his schemes. ‘What I want,’ he said, ‘is someone to come with me as financial adviser. What about you, Archie? You’ve always had a good head on your shoulders. You were Head of the School at Clift on, you’ve had all this experience in the City. You’re just the man I want.’

‘I couldn’t leave my job,’ said Archie.

‘Why not? Put it to your boss properly – point out it will widen your experience and all that. He’ll keep the job open for you, I expect.’

Archie said he doubted if Mr Goldstein would do anything of the kind.

‘Well, think it over, my boy. I’d like to have you. Agatha could come too, of course. She likes travelling, doesn’t she?’

‘Yes,’ I said – a monosyllable of understatement.

‘I’ll tell you what the itinerary is. We go first to South Africa. You and me, and a secretary, of course. With us would be going the Hyams. I don’t know if you know Hyam – he’s a potato king from East Anglia. A very sound fellow. He’s a great friend of mine. He’d bring his wife and daughter. They’d only go as far as South Africa. Hyam can’t afford to come further because he has got too many business deals on here. After that we push on to Australia; and after Australia New Zealand. I’m going to take a bit of time off in New Zealand – I’ve got a lot of friends out there; I like the country. We’d have, perhaps, a month’s holiday. You could go on to Hawaii, if you liked, Honolulu.’

‘Honolulu,’ I breathed. It sounded like the kind of phantasy you had in dreams.

‘Then on to Canada, and so home. It would take about nine to ten months. What about it?’

We realised at last that he really meant it. We went into the thing fairly carefully. Archie’s expenses would, of course, all be paid, and outside that he would be offered a fee of £1000. If I accompanied the party practically all my travelling costs would be paid, since I would accompany Archie as his wife, and free transport was being given on ships and on the national railways of the various countries.

We worked furiously over finances. It seemed, on the whole, that it could be done. Archie’s £1000 ought to cover my expenses in hotels, and a month’s holiday for both of us in Honolulu. It would be a near thing, but we thought it was just possible.

Archie and I had twice gone abroad for a short holiday: once to the south of France, to the Pyrenees, and once to Switzerland. We both loved travelling – I had certainly been given a taste for it by that early experience when I was seven years old. Anyway, I longed to see the world, and it seemed to me highly probable that I never should. We were now committed to the business life, and a business man, as far as I could see, never got more than a fortnight’s holiday a year. A fortnight would not take you far. I longed to see China and Japan and India and Hawaii, and a great many other places, but my dream remained, and probably always would remain, wishful thinking.

‘It’s a risk,’ I said. ‘A terrible risk.’

‘Yes, it’s a risk. I realise we shall probably land up back in England without a penny, with a little over a hundred a year between us, and nothing else; that jobs will be hard to get – probably even harder than now. On the other hand, well – if you don’t take a risk you never get anywhere, do you?’

‘It’s rather up to you,’ Archie said. ‘What shall we do about Teddy?’ Teddy was our name for Rosalind at that time – I think because we had once called her in fun The Tadpole.

‘Punkie’ – the name we all used for Madge now – would take Teddy. Or mother – they would be delighted. And she’s got Nurse. Yes – yes – that part of it is all right. It’s the only chance we shall ever have, I said wistfully.

We thought about it, and thought about it.

‘Of course – you could go,’ I said, bracing myself to be unselfish, ‘and I stay behind.’

I looked at him. He looked at me.

‘I’m not going to leave you behind,’ he said. ‘I wouldn’t enjoy it if I did that. No, either you risk it and come too, or not – but it’s up to you, because you risk more than I do, really.’

So again we sat and thought, and I adopted Archie’s point of view.

‘I think you’re right,’ I said. ‘It’s our chance. If we don’t do it we shall always be mad with ourselves. No, as you say, if you can’t take the risk of doing something you want, when the chance comes, life isn’t worth living.’

We had never been people who played safe. We had persisted in marrying against all opposition, and now we were determined to see the world and risk what would happen on our return.

Our home arrangements were not difficult. The Addison Mansions flat could be let advantageously, and that would pay Jessie’s wages. My mother and my sister were delighted to have Rosalind and Nurse. The only opposition of any kind came at the last moment, when we learnt that my brother Monty was coming home on leave from Africa. My sister was outraged that I was not going to stay in England for his visit.

‘Your only brother, coming back after being wounded in the war, and having been away for years, and you choose to go off round the world at that moment. I think it’s disgraceful. You ought to put your brother first.’

‘Well, I don’t think so,’ I said. ‘I ought to put my husband first. He is going on this trip and I’m going with him. Wives should go with their husbands.’

‘Monty’s your only brother, and it’s your only chance of seeing him, perhaps for years more.’

She quite upset me in the end; but my mother was strongly on my side. ‘A wife’s duty is to go with her husband,’ she said. ‘A husband must come first, even before your children – and a brother is further away still. Remember, if you’re not with your husband, if you leave him too much, you’ll lose him. That’s specially true of a man like Archie.’