По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

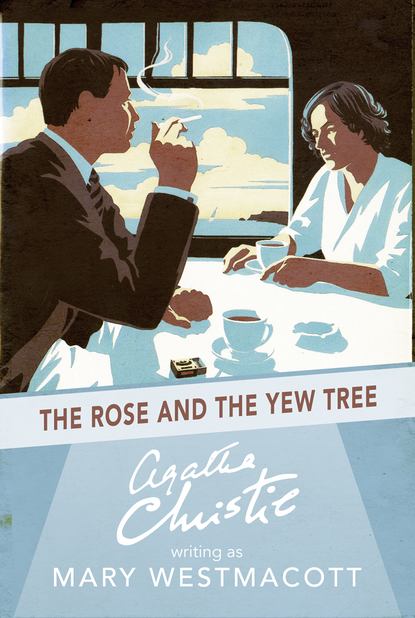

The Rose and the Yew Tree

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Agatha Christie (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PRELUDE (#ulink_8e0c50ef-bf6f-5178-b07f-582f65e9bcb2)

I was in Paris when Parfitt, my man, came to me and said that a lady had called to see me. She said, he added, that it was very important.

I had formed by then the habit of never seeing people without an appointment. People who call to see you about urgent business are nearly invariably people who wish for financial assistance. The people who are in real need of financial assistance, on the other hand, hardly ever come and ask for it.

I asked Parfitt what my visitor’s name was, and he proffered a card. The card said: Catherine Yougoubian—a name I had never heard of and which, frankly, I did not much fancy. I revised my idea that she needed financial assistance and deduced instead that she had something to sell—probably one of those spurious antiques which command a better price when they are brought by hand and forced on the unwilling buyer with the aid of voluble patter.

I said I was sorry that I could not see Madame Yougoubian, but she could write and state her business.

Parfitt inclined his head and withdrew. He is very reliable—an invalid such as I am needs a reliable attendant—and I had not the slightest doubt that the matter was now disposed of. Much to my astonishment, however, Parfitt reappeared. The lady, he said, was very insistent. It was a matter of life and death and concerned an old friend of mine.

Whereupon my curiosity was suddenly aroused. Not by the message—that was a fairly obvious gambit; life and death and the old friend are the usual counters in the game. No, what stimulated my curiosity was the behaviour of Parfitt. It was not like Parfitt to come back with a message of that kind.

I jumped, quite wrongly, to the conclusion that Catherine Yougoubian was incredibly beautiful, or at any rate unusually attractive. Nothing else, I thought, would explain Parfitt’s behaviour.

And since a man is always a man, even if he be fifty and a cripple, I fell into the snare. I wanted to see this radiant creature who could overcome the defences of the impeccable Parfitt.

So I told him to bring the lady up—and when Catherine Yougoubian entered the room, revulsion of feeling nearly took my breath away!

True, I understand Parfitt’s behaviour well enough now. His judgment of human nature is quite unerring. He recognized in Catherine that persistence of temperament against which, in the end, all defences fall. Wisely, he capitulated straight away and saved himself a long and wearying battle. For Catherine Yougoubian has the persistence of a sledgehammer and the monotony of an oxyacetylene blowpipe: combined with the wearing effect of water dropping on a stone! Time is infinite for her if she wishes to achieve her object. She would have sat determinedly in my entrance hall all day. She is one of those women who have room in their heads for one idea only—which gives them an enormous advantage over less single-minded individuals.

As I say, the shock I got when she entered the room was tremendous. I was all keyed up to behold beauty. Instead, the woman who entered was monumentally, almost awe-inspiringly, plain. Not ugly, mark you; ugliness has its own rhythm, its own mode of attack, but Catherine had a large flat face like a pancake—a kind of desert of a face. Her mouth was wide and had a slight—a very slight—moustache on its upper lip. Her eyes were small and dark and made one think of inferior currants in an inferior bun. Her hair was abundant, ill-confined, and pre-eminently greasy. Her figure was so nondescript that it was practically not a figure at all. Her clothes covered her adequately and fitted her nowhere. She appeared neither destitute nor opulent. She had a determined jaw and, as I heard when she opened her mouth, a harsh and unlovely voice.

I threw a glance of deep reproach at Parfitt who met it imperturbably. He was clearly of the opinion that, as usual, he knew best.

‘Madame Yougoubian, sir,’ he said, and retired, shutting the door and leaving me at the mercy of this determined-looking female.

Catherine advanced upon me purposefully. I had never felt so helpless, so conscious of my crippled state. This was a woman from whom it would be advisable to run away, and I could not run.

She spoke in a loud firm voice.

‘Please—if you will be so good—you must come with me, please?’

It was less of a request than a command.

‘I beg your pardon?’ I said, startled.

‘I do not speak the English too good, I am afraid. But there is not time to lose—no, no time at all. It is to Mr Gabriel I ask you to come. He is very ill. Soon, very soon, he dies, and he has asked for you. So to see him you must come at once.’

I stared at her. Frankly, I thought she was crazy. The name Gabriel made no impression upon me at all, partly, I daresay, because of her pronunciation. It did not sound in the least like Gabriel. But even if it had sounded like it, I do not think that it would have stirred a chord. It was all so long ago. It must have been ten years since I had even thought of John Gabriel.

‘You say someone is dying? Someone—er—that I know?’

She cast at me a look of infinite reproach.

‘But yes, you know him—you know him well—and he asks for you.’

She was so positive that I began to rack my brains. What name had she said? Gable? Galbraith? I had known a Galbraith, a mining engineer. Only casually, it is true; it seemed in the highest degree unlikely that he should ask to see me on his deathbed. Yet it is a tribute to Catherine’s force of character that I did not doubt for a moment the truth of her statement.

‘What name did you say?’ I asked. ‘Galbraith?’

‘No—no. Gabriel. Gabriel!’

I stared. This time I got the word right, but it only conjured up a mental vision of the Angel Gabriel with a large pair of wings. The vision fitted in well enough with Catherine Yougoubian. She had a resemblance to the type of earnest woman usually to be found kneeling in the extreme left-hand corner of an early Italian Primitive. She had that peculiar simplicity of feature combined with the look of ardent devotion.

She added, persistently, doggedly, ‘John Gabriel—’ and I got it!

It all came back to me. I felt giddy and slightly sick. St Loo, and the old ladies, and Milly Burt, and John Gabriel with his ugly dynamic little face, rocking gently back on his heels. And Rupert, tall and handsome like a young god. And, of course, Isabella …

I remembered the last time I had seen John Gabriel in Zagrade and what had happened there, and I felt rising in me a surging red tide of anger and loathing …

‘So he’s dying, is he?’ I asked savagely. ‘I’m delighted to hear it!’

‘Pardon?’

There are things that you cannot very well repeat when someone says ‘Pardon?’ politely to you. Catherine Yougoubian looked utterly uncomprehending. I merely said:

‘You say he is dying?’

‘Yes. He is in pain—in terrible pain.’

Well, I was delighted to hear that, too. No pain that John Gabriel could suffer would atone for what he had done. But I felt unable to say so to one who was evidently John Gabriel’s devoted worshipper.

What was there about the fellow, I wondered irritably, that always made women fall for him? He was ugly as sin. He was pretentious, vulgar, boastful. He had brains of a kind, and he was, in certain circumstances (low circumstances!) good company. He had humour. But none of these are really characteristics that appeal to women very much.

Catherine broke in upon my thoughts.

‘You will come, please? You will come quickly? There is no time to lose.’

I pulled myself together.

‘I’m sorry, my dear lady,’ I said, ‘but I’m afraid I cannot accompany you.’

‘But he asks for you,’ she persisted.

‘I’m not coming,’ I said.