По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

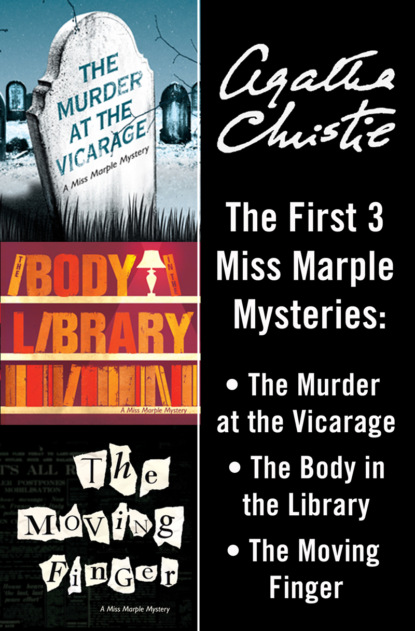

Miss Marple 3-Book Collection 1: The Murder at the Vicarage, The Body in the Library, The Moving Finger

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Oh, I wouldn’t say that, Colonel Melchett,’ said Miss Marple.

‘Why, can you think of anyone else?’

‘Oh! yes, indeed. Why,’ she counted on her fingers, ‘one, two, three, four, five, six – yes, and a possible seven. I can think of at least seven people who might be very glad to have Colonel Protheroe out of the way.’

The Colonel looked at her feebly.

‘Seven people? In St Mary Mead?’

Miss Marple nodded brightly.

‘Mind you I name no names,’ she said. ‘That wouldn’t be right. But I’m afraid there’s a lot of wickedness in the world. A nice honourable upright soldier like you doesn’t know about these things, Colonel Melchett.’

I thought the Chief Constable was going to have apoplexy.

Chapter 10 (#ulink_3576673e-5795-5c42-9837-6b345cf6663e)

His remarks on the subject of Miss Marple as we left the house were far from complimentary.

‘I really believe that wizened-up old maid thinks she knows everything there is to know. And hardly been out of this village all her life. Preposterous. What can she know of life?’

I said mildly that though doubtless Miss Marple knew next to nothing of Life with a capital L, she knew practically everything that went on in St Mary Mead.

Melchett admitted that grudgingly. She was a valuable witness – particularly valuable from Mrs Protheroe’s point of view.

‘I suppose there’s no doubt about what she says, eh?’

‘If Miss Marple says she had no pistol with her, you can take it for granted that it is so,’ I said. ‘If there was the least possibility of such a thing, Miss Marple would have been on to it like a knife.’

‘That’s true enough. We’d better go and have a look at the studio.’

The so-called studio was a mere rough shed with a skylight. There were no windows and the door was the only means of entrance or egress. Satisfied on this score, Melchett announced his intention of visiting the Vicarage with the Inspector.

‘I’m going to the police station now.’

As I entered through the front door, a murmur of voices caught my ear. I opened the drawing-room door.

On the sofa beside Griselda, conversing animatedly, sat Miss Gladys Cram. Her legs, which were encased in particularly shiny pink stockings, were crossed, and I had every opportunity of observing that she wore pink striped silk knickers.

‘Hullo, Len,’ said Griselda.

‘Good morning, Mr Clement,’ said Miss Cram. ‘Isn’t the news about the Colonel really too awful? Poor old gentleman.’

‘Miss Cram,’ said my wife, ‘very kindly came in to offer to help us with the Guides. We asked for helpers last Sunday, you remember.’

I did remember, and I was convinced, and so, I knew from her tone, was Griselda, that the idea of enrolling herself among them would never have occurred to Miss Cram but for the exciting incident which had taken place at the Vicarage.

‘I was only just saying to Mrs Clement,’ went on Miss Cram, ‘you could have struck me all of a heap when I heard the news. A murder? I said. In this quiet one-horse village – for quiet it is, you must admit – not so much as a picture house, and as for Talkies! And then when I heard it was Colonel Protheroe – why, I simply couldn’t believe it. He didn’t seem the kind, somehow, to get murdered.’

‘And so,’ said Griselda, ‘Miss Cram came round to find out all about it.’

I feared this plain speaking might offend the lady, but she merely flung her head back and laughed uproariously, showing every tooth she possessed.

‘That’s too bad. You’re a sharp one, aren’t you, Mrs Clement? But it’s only natural, isn’t it, to want to hear the ins and outs of a case like this? And I’m sure I’m willing enough to help with the Guides in any way you like. Exciting, that’s what it is. I’ve been stagnating for a bit of fun. I have, really I have. Not that my job isn’t a very good one, well paid, and Dr Stone quite the gentleman in every way. But a girl wants a bit of life out of office hours, and except for you, Mrs Clement, who is there in the place to talk to except a lot of old cats?’

‘There’s Lettice Protheroe,’ I said.

Gladys Cram tossed her head.

‘She’s too high and mighty for the likes of me. Fancies herself the county, and wouldn’t demean herself by noticing a girl who had to work for her living. Not but what I did hear her talking of earning her living herself. And who’d employ her, I should like to know? Why, she’d be fired in less than a week. Unless she went as one of those mannequins, all dressed up and sidling about. She could do that, I expect.’

‘She’d make a very good mannequin,’ said Griselda. ‘She’s got such a lovely figure.’ There’s nothing of the cat about Griselda. ‘When was she talking of earning her own living?’

Miss Cram seemed momentarily discomfited, but recovered herself with her usual archness.

‘That would be telling, wouldn’t it?’ she said. ‘But she did say so. Things not very happy at home, I fancy. Catch me living at home with a stepmother. I wouldn’t sit down under it for a minute.’

‘Ah! but you’re so high spirited and independent,’ said Griselda gravely, and I looked at her with suspicion.

Miss Cram was clearly pleased.

‘That’s right. That’s me all over. Can be led, not driven. A palmist told me that not so very long ago. No. I’m not one to sit down and be bullied. And I’ve made it clear all along to Dr Stone that I must have my regular times off. These scientific gentlemen, they think a girl’s a kind of machine – half the time they just don’t notice her or remember she’s there. Of course, I don’t know much about it,’ confessed the girl.

‘Do you find Dr Stone pleasant to work with? It must be an interesting job if you are interested in archaeology.’

‘It still seems to me that digging up people that are dead and have been dead for hundreds of years isn’t – well, it seems a bit nosy, doesn’t it? And there’s Dr Stone so wrapped up in it all, that half the time he’d forget his meals if it wasn’t for me.’

‘Is he at the barrow this morning?’ asked Griselda.

Miss Cram shook her head.

‘A bit under the weather this morning,’ she explained. ‘Not up to doing any work. That means a holiday for little Gladys.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said.

‘Oh! It’s nothing much. There’s not going to be a second death. But do tell me, Mr Clement, I hear you’ve been with the police all morning. What do they think?’

‘Well,’ I said slowly, ‘there is still a little – uncertainty.’

‘Ah!’ cried Miss Cram. ‘Then they don’t think it is Mr Lawrence Redding after all. So handsome, isn’t he? Just like a movie star. And such a nice smile when he says good morning to you. I really couldn’t believe my ears when I heard the police had arrested him. Still, one has always heard they’re very stupid – the county police.’

‘You can hardly blame them in this instance,’ I said. ‘Mr Redding came in and gave himself up.’

‘What?’ the girl was clearly dumbfounded. ‘Well – of all the poor fish! If I’d committed a murder, I wouldn’t go straight off and give myself up. I should have thought Lawrence Redding would have had more sense. To give in like that! What did he kill Protheroe for? Did he say? Was it just a quarrel?’

‘It’s not absolutely certain that he did kill him,’ I said.

‘But surely – if he says he has – why really, Mr Clement, he ought to know.’