По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

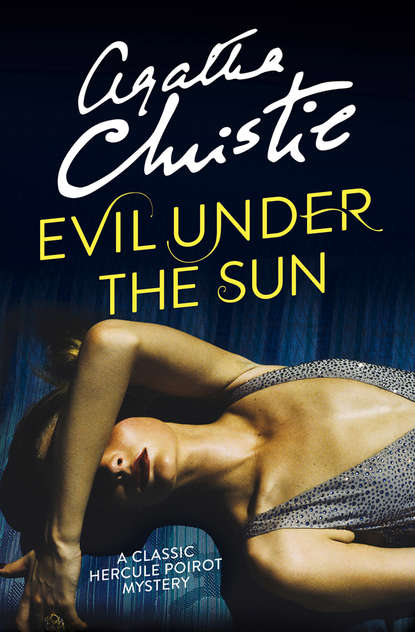

Evil Under the Sun

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It may be, yes.’

‘All the same,’ Mrs Gardener knitted with energy, ‘I’m inclined to agree with you on one point. These girls that lie out like that in the sun will grow hair on their legs and arms. I’ve said so to Irene—that’s my daughter, M. Poirot. Irene, I said to her, if you lie out like that in the sun, you’ll have hair all over you, hair on your arms and hair on your legs and hair on your bosom, and what will you look like then? I said to her. Didn’t I, Odell?’

‘Yes, darling,’ said Mr Gardener.

Everyone was silent, perhaps making a mental picture of Irene when the worst had happened.

Mrs Gardener rolled up her knitting and said:

‘I wonder now—’

Mr Gardener said:

‘Yes, darling?’

He struggled out of the hammock chair and took Mrs Gardener’s knitting and her book. He asked:

‘What about joining us for a drink, Miss Brewster?’

‘Not just now, thanks.’

The Gardeners went up to the hotel.

Miss Brewster said:

‘American husbands are wonderful!’

III

Mrs Gardener’s place was taken by the Reverend Stephen Lane.

Mr Lane was a tall vigorous clergyman of fifty odd. His face was tanned and his dark grey flannel trousers were holidayfied and disreputable.

He said with enthusiasm:

‘Marvellous country! I’ve been from Leathercombe Bay to Harford and back over the cliffs.’

‘Warm work walking today,’ said Major Barry who never walked.

‘Good exercise,’ said Miss Brewster. ‘I haven’t been for my row yet. Nothing like rowing for your stomach muscles.’

The eyes of Hercule Poirot dropped somewhat ruefully to a certain protuberance in his middle.

Miss Brewster, noting the glance, said kindly:

‘You’d soon get that off, M. Poirot, if you took a rowing-boat out every day.’

‘Merci, Mademoiselle. I detest boats!’

‘You mean small boats?’

‘Boats of all sizes!’ He closed his eyes and shuddered. ‘The movement of the sea, it is not pleasant.’

‘Bless the man, the sea is as calm as a mill pond today.’

Poirot replied with conviction:

‘There is no such thing as a really calm sea. Always, always, there is motion.’

‘If you ask me,’ said Major Barry, ‘seasickness is nine-tenths nerves.’

‘There,’ said the clergyman, smiling a little, ‘speaks the good sailor—eh, Major?’

‘Only been ill once—and that was crossing the Channel! Don’t think about it, that’s my motto.’

‘Seasickness is really a very odd thing,’ mused Miss Brewster. ‘Why should some people be subject to it and not others? It seems so unfair. And nothing to do with one’s ordinary health. Quite sickly people are good sailors. Someone told me once it was something to do with one’s spine. Then there’s the way some people can’t stand heights. I’m not very good myself, but Mrs Redfern is far worse. The other day, on the cliff path to Harford, she turned quite giddy and simply clung to me. She told me she once got stuck halfway down that outside staircase on Milan Cathedral. She’d gone up without thinking but coming down did for her.’

‘She’d better not go down the ladder to Pixy Cove, then,’ observed Lane.

Miss Brewster made a face.

‘I funk that myself. It’s all right for the young. The Cowan boys and the young Mastermans, they run up and down and enjoy it.’

Lane said.

‘Here comes Mrs Redfern now, coming up from her bathe.’

Miss Brewster remarked:

‘M. Poirot ought to approve of her. She’s no sun-bather.’

Young Mrs Redfern had taken off her rubber cap and was shaking out her hair. She was an ash blonde and her skin was of that dead fairness that goes with that colouring. Her legs and arms were very white.

With a hoarse chuckle, Major Barry said:

‘Looks a bit uncooked among the others, doesn’t she?’

Wrapping herself in a long bath-robe Christine Redfern came up the beach and mounted the steps towards them.

She had a fair serious face, pretty in a negative way and small dainty hands and feet.

She smiled at them and dropped down beside them, tucking her bath-wrap round her.

Miss Brewster said:

‘You have earned M. Poirot’s good opinion. He doesn’t like the sun-tanning crowd. Says they’re like joints of butcher’s meat, or words to that effect.’

Christine Redfern smiled ruefully. She said: