По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

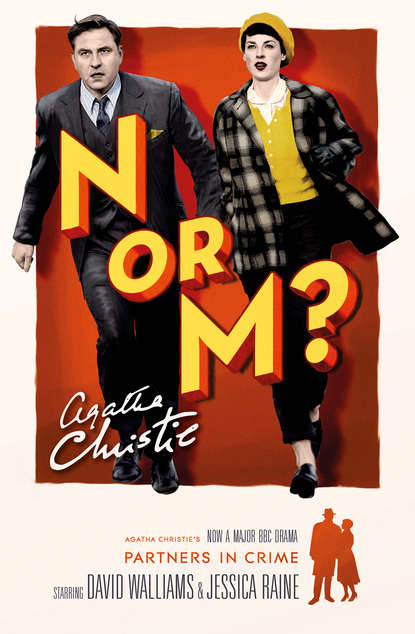

N or M?

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She opened the door to find a broad-shouldered man with a big fair moustache and a cheerful red face, standing on the mat.

His glance, a quick one, took her in as he asked in a pleasant voice:

‘Are you Mrs Beresford?’

‘Yes.’

‘My name’s Grant. I’m a friend of Lord Easthampton’s. He suggested I should look you and your husband up.’

‘Oh, how nice, do come in.’

She preceded him into the sitting-room.

‘My husband, er—Captain—’

‘Mr.’

‘Mr Grant. He’s a friend of Mr Car—of Lord Easthampton’s.’

The old nom de guerre of the former Chief of the Intelligence, ‘Mr Carter’, always came more easily to her lips than their old friend’s proper title.

For a few minutes the three talked happily together. Grant was an attractive person with an easy manner.

Presently Tuppence left the room. She returned a few minutes later with the sherry and some glasses.

After a few minutes, when a pause came, Mr Grant said to Tommy:

‘I hear you’re looking for a job, Beresford?’

An eager light came into Tommy’s eye.

‘Yes, indeed. You don’t mean—’

Grant laughed, and shook his head.

‘Oh, nothing of that kind. No, I’m afraid that has to be left to the young active men—or to those who’ve been at it for years. The only things I can suggest are rather stodgy, I’m afraid. Office work. Filing papers. Tying them up in red tape and pigeon-holing them. That sort of thing.’

Tommy’s face fell.

‘Oh, I see!’

Grant said encouragingly:

‘Oh well, it’s better than nothing. Anyway, come and see me at my office one day. Ministry of Requirements. Room 22. We’ll fix you up with something.’

The telephone rang. Tuppence picked up the receiver.

‘Hallo—yes—what?’ A squeaky voice spoke agitatedly from the other end. Tuppence’s face changed. ‘When?—Oh, my dear—of course—I’ll come over right away…’

She put back the receiver.

She said to Tommy:

‘That was Maureen.’

‘I thought so—I recognised her voice from here.’

Tuppence explained breathlessly:

‘I’m so sorry, Mr Grant. But I must go round to this friend of mine. She’s fallen and twisted her ankle and there’s no one with her but her little girl, so I must go round and fix up things for her and get hold of someone to come in and look after her. Do forgive me.’

‘Of course, Mrs Beresford. I quite understand.’

Tuppence smiled at him, picked up a coat which had been lying over the sofa, slipped her arms into it and hurried out. The flat door banged.

Tommy poured out another glass of sherry for his guest.

‘Don’t go yet,’ he said.

‘Thank you.’ The other accepted the glass. He sipped it for a moment in silence. Then he said, ‘In a way, you know, your wife’s being called away is a fortunate occurrence. It will save time.’

Tommy stared.

‘I don’t understand.’

Grant said deliberately:

‘You see, Beresford, if you had come to see me at the Ministry, I was empowered to put a certain proposition before you.’

The colour came slowly up in Tommy’s freckled face. He said:

‘You don’t mean—’

Grant nodded.

‘Easthampton suggested you,’ he said. ‘He told us you were the man for the job.’

Tommy gave a deep sigh.

‘Tell me,’ he said.

‘This is strictly confidential, of course.’

Tommy nodded.

‘Not even your wife must know. You understand?’

‘Very well—if you say so. But we worked together before.’