По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

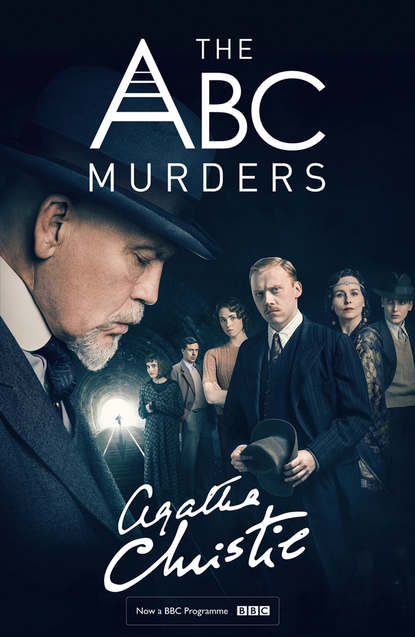

The ABC Murders

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Poirot,’ I cried. ‘You have dyed your hair!’

‘Ah, the comprehension comes to you!’

‘So that’s why your hair looks so much blacker than it did last time I was back.’

‘Exactly.’

‘Dear me,’ I said, recovering from the shock. ‘I suppose next time I come home I shall find you wearing false moustaches—or are you doing so now?’

Poirot winced. His moustaches had always been his sensitive point. He was inordinately proud of them. My words touched him on the raw.

‘No, no, indeed, mon ami. That day, I pray the good God, is still far off. The false moustache! Quel horreur!’

He tugged at them vigorously to assure me of their genuine character.

‘Well, they are very luxuriant still,’ I said.

‘N’est ce pas? Never, in the whole of London, have I seen a pair of moustaches to equal mine.’

A good job too, I thought privately. But I would not for the world have hurt Poirot’s feelings by saying so.

Instead I asked if he still practised his profession on occasion.

‘I know,’ I said, ‘that you actually retired years ago—’

‘C’est vrai. To grow the vegetable marrows! And immediately a murder occurs—and I send the vegetable marrows to promenade themselves to the devil. And since then—I know very well what you will say—I am like the prima donna who makes positively the farewell performance! That farewell performance, it repeats itself an indefinite number of times!’

I laughed.

‘In truth, it has been very like that. Each time I say: this is the end. But no, something else arises! And I will admit it, my friend, the retirement I care for it not at all. If the little grey cells are not exercised, they grow the rust.’

‘I see,’ I said. ‘You exercise them in moderation.’

‘Precisely. I pick and choose. For Hercule Poirot nowadays only the cream of crime.’

‘Has there been much cream about?’

‘Pas mal. Not long ago I had a narrow escape.’

‘Of failure?’

‘No, no.’ Poirot looked shocked. ‘But I—I, Hercule Poirot, was nearly exterminated.’

I whistled.

‘An enterprising murderer!’

‘Not so much enterprising as careless,’ said Poirot. ‘Precisely that—careless. But let us not talk of it. You know, Hastings, in many ways I regard you as my mascot.’

‘Indeed?’ I said. ‘In what ways?’

Poirot did not answer my question directly. He went on:

‘As soon as I heard you were coming over I said to myself: something will arise. As in former days we will hunt together, we two. But if so it must be no common affair. It must be something’—he waved his hands excitedly—‘something recherché—delicate—fine…’ He gave the last untranslatable word its full flavour.

‘Upon my word, Poirot,’ I said. ‘Anyone would think you were ordering a dinner at the Ritz.’

‘Whereas one cannot command a crime to order? Very true.’ He sighed. ‘But I believe in luck—in destiny, if you will. It is your destiny to stand beside me and prevent me from committing the unforgivable error.’

‘What do you call the unforgivable error?’

‘Overlooking the obvious.’

I turned this over in my mind without quite seeing the point.

‘Well,’ I said presently, smiling, ‘has this super crime turned up yet?’

‘Pas encore. At least—that is—’

He paused. A frown of perplexity creased his forehead. His hands automatically straightened an object or two that I had inadvertently pushed awry.

‘I am not sure,’ he said slowly.

There was something so odd about his tone that I looked at him in surprise.

The frown still lingered.

Suddenly with a brief decisive nod of the head he crossed the room to a desk near the window. Its contents, I need hardly say, were all neatly docketed and pigeon-holed so that he was able at once to lay his hand upon the paper he wanted.

He came slowly across to me, an open letter in his hand. He read it through himself, then passed it to me.

‘Tell me, mon ami,’ he said. ‘What do you make of this?’

I took it from him with some interest.

It was written on thickish white notepaper in printed characters:

Mr Hercule Poirot,—You fancy yourself, don’t you, at solving mysteries that are too difficult for our poor thick-headed British police? Let us see, Mr Clever Poirot, just how clever you can be. Perhaps you’ll find this nut too hard to crack. Look out for Andover, on the 21st of the month.

Yours, etc.,

A B C.

I glanced at the envelope. That also was printed.

‘Postmarked WC1,’ said Poirot as I turned my attention to the postmark. ‘Well, what is your opinion?’

I shrugged my shoulders as I handed it back to him.