По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

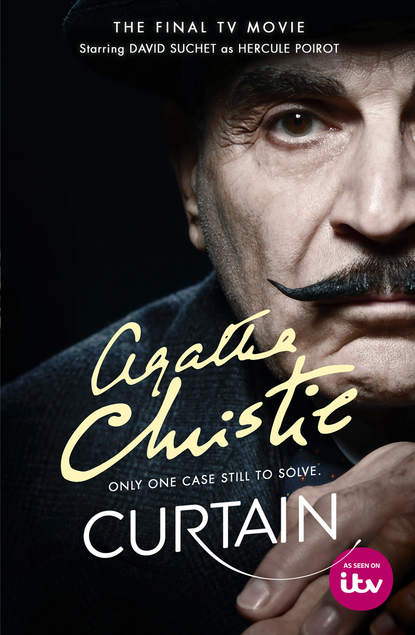

Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Not in the least. I do not feel like that at all.’

‘They were good days,’ I said sadly.

‘You may speak for yourself, Hastings. For me, my arrival at Styles St Mary was a sad and painful time. I was a refugee, wounded, exiled from home and country, existing by charity in a foreign land. No, it was not gay. I did not know then that England would come to be my home and that I should find happiness here.’

‘I had forgotten that,’ I admitted.

‘Precisely. You attribute always to others the sentiments that you yourself experience. Hastings was happy – everybody was happy!’

‘No, no,’ I protested, laughing.

‘And in any case it is not true,’ continued Poirot. ‘You look back, you say, the tears rising in your eyes, “Oh, the happy days. Then I was young.” But indeed, my friend, you were not so happy as you think. You had recently been severely wounded, you were fretting at being no longer fit for active service, you had just been depressed beyond words by your sojourn in a dreary convalescent home and, as far as I remember, you proceeded to complicate matters by falling in love with two women at the same time.’

I laughed and flushed.

‘What a memory you have, Poirot.’

‘Ta ta ta – I remember now the melancholy sigh you heaved as you murmured fatuities about two lovely women.’

‘Do you remember what you said? You said, “And neither of them for you! But courage, mon ami. We may hunt together again and then perhaps –”’

I stopped. For Poirot and I had gone hunting again to France and it was there that I had met the one woman . . .

Gently my friend patted my arm.

‘I know, Hastings, I know. The wound is still fresh. But do not dwell on it, do not look back. Instead look forward.’

I made a gesture of disgust.

‘Look forward? What is there to look forward to?’

‘Eh bien, my friend, there is work to be done.’

‘Work? Where?’

‘Here.’

I stared at him.

‘Just now,’ said Poirot, ‘you asked me why I had come here. You may not have observed that I gave you no answer. I will give the answer now. I am here to hunt down a murderer.’

I stared at him with even more astonishment. For a moment I thought he was rambling.

‘You really mean that?’

‘But certainly I mean it. For what other reason did I urge you to join me? My limbs, they are no longer active, but my brain, as I told you, is unimpaired. My rule, remember, has been always the same – sit back and think. That I still can do – in fact it is the only thing possible for me. For the more active side of the campaign I shall have with me my invaluable Hastings.’

‘You really mean it?’ I gasped.

‘Of course I mean it. You and I, Hastings, are going hunting once again.’

It took some minutes to grasp that Poirot was really in earnest.

Fantastic though his statement sounded, I had no reason to doubt his judgement.

With a slight smile he said, ‘At last you are convinced. At first you imagined, did you not, that I had the softening of the brain?’

‘No, no,’ I said hastily. ‘Only this seems such an unlikely place.’

‘Ah, you think so?’

‘Of course I haven’t seen all the people yet –’

‘Whom have you seen?’

‘Just the Luttrells, and a man called Norton, seems an inoffensive chap, and Boyd Carrington – I must say I took the greatest fancy to him.’

Poirot nodded. ‘Well, Hastings, I will tell you this, when you have seen the rest of the household, my statement will seem to you just as improbable as it is now.’

‘Who else is there?’

‘The Franklins – Doctor and Mrs, the hospital nurse who attends to Mrs Franklin, your daughter Judith. Then there is a man called Allerton, something of a lady-killer, and a Miss Cole, a woman in her thirties. They are all, let me tell you, very nice people.’

‘And one of them is a murderer?’

‘And one of them is a murderer.’

‘But why – how – why should you think –?’

I found it hard to frame my questions, they tumbled over each other.

‘Calm yourself, Hastings. Let us begin from the beginning. Reach me, I pray you, that small box from the bureau. Bien. And now the key – so –’

Unlocking the despatch case, he took from it a mass of typescript and newspaper clippings.

‘You can study these at your leisure, Hastings. For the moment I should not bother with the newspaper cuttings. They are merely the press accounts of various tragedies, occasionally inaccurate, sometimes suggestive. To give you an idea of the cases I suggest that you should read through the précis I have made.’

Deeply interested, I started reading.

CASE A. ETHERINGTON

Leonard Etherington. Unpleasant habits – took drugs and also drank. A peculiar and sadistic character. Wife young and attractive. Desperately unhappy with him. Etherington died, apparently of food poisoning. Doctor not satisfied. As a result of autopsy, death discovered to be due to arsenical poisoning. Supply of weed-killer in the house, but ordered a long time previously. Mrs Etherington arrested and charged with murder. She had recently been friends with a man in Civil Service returning to India. No suggestion of actual infidelity, but evidence of deep sympathy between them. Young man had since become engaged to be married to girl he met on voyage out. Some doubt as to whether letter telling Mrs Etherington of this fact was received by her after or before her husband’s death. She herself says before. Evidence against her mainly circumstantial, absence of another likely suspect and accident highly unlikely. Great sympathy felt with her at trial owing to husband’s character and the bad treatment she had received from him. Judge’s summing up was in her favour stressing that verdict must be beyond any reasonable doubt.

Mrs Etherington was acquitted. General opinion, however, was that she was guilty. Her life afterwards very difficult owing to friends, etc., cold shouldering her. She died as a result of taking an overdose of sleeping draught two years after the trial. Verdict of accidental death returned at inquest.

CASE B. MISS SHARPLES

Elderly spinster. An invalid. Difficult, suffering much pain.