По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

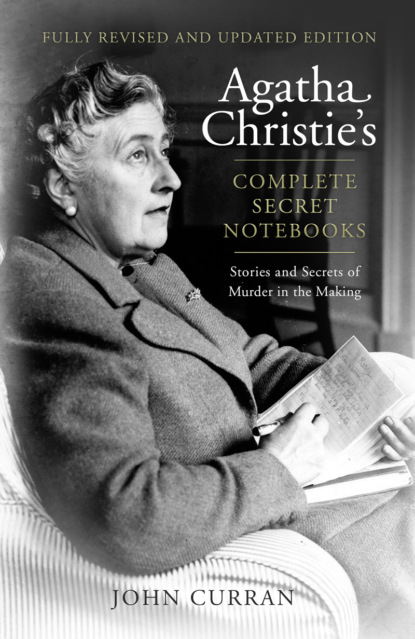

Agatha Christie’s Complete Secret Notebooks

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Some of them are more worthy recipients of their contents: hard-backed multi-paged notebooks with marbled covers or spiral binding with embossed covers; some are even grandly inscribed on the cover ‘Manuscript’. Notebook 7 is described inside the back cover as ‘spongeable PVC cover from WHS’, and Notebook 71 is a ‘Cahier’ with ‘Agatha Miller 31 Mai 1907’ written on the cover and containing French homework from her time in Paris as a young woman. Notebook 31 is an impressive wine-coloured hardback from Langley and Sons Ltd., Tottenham Court Rd. and costing 1s 3d (6p).

In a few cases their unpretentiousness is now a liability as some of them have suffered on their journey down the years – they have lost their covers (and perhaps some pages – who knows?), staples have become rusted, pencil has faded and in some cases the quality of the paper, combined with the use of a leaky biro, has meant that notes written on one page have seeped on to the reverse also. And, of course, as many of them date from the war years, paper quality was often poor.

It would seem that some Notebooks originally belonged to, or were temporarily commandeered by, Christie’s (then young) daughter Rosalind, as her name and address in her own neat handwriting appears on the inside cover (Notebook 41). And Notebook 73, otherwise blank, has her first husband Archie Christie’s name in flowing script inside the front cover. The name and address lines on the front cover of Notebook 19 have been filled in: ‘Mallowan, 17 Lawn Road Flats’.

The number of pages Christie used in each Notebook varies greatly – Notebook 35 has 220 pages of notes while Notebook 72 has a mere five; Notebook 63 has notes on over 150 pages but Notebook 42 uses only 20. The average lies somewhere between 100 and 120.

Although they are collectively referred to as ‘The Notebooks of Agatha Christie’, not all of them are concerned with her literary output. Notebooks 11, 40 and 55 consist solely of chemical formulae and seem to date from her days as a student dispenser; Notebook 71 contains French homework and Notebook 73 is completely blank. Moreover, she often used them for making random notes, sometimes on the inside covers – there is a list of ‘furniture for 48’ [Sheffield Terrace] in Notebook 59; Notebook 67 has reminders to ring up Collins and to make a hair appointment; Notebook 68 has a list of train times from Stockport to Torquay. And her husband Max Mallowan has written accurately in his small, neat hand, ‘The Pale Horse’ on the front of Notebook 54.

… what I invariably do is lose the exercise book …

In a career spanning over half a century and two world wars, some loss is inevitable but reassuringly this seems to have happened hardly at all. Of course, we cannot be sure how many Notebooks there should be, but the 73 we still have are an impressive legacy.

Nevertheless, no notes or outlines exists for The Murder on the Links (1923), The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), The Big Four (1927) or The Seven Dials Mystery (1929). From the 1920s we have notes only for The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), The Man in the Brown Suit (1924), The Secret of Chimneys (1925) and The Mystery of the Blue Train (1928). When we remember that The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was published just before Christie’s traumatic disappearance and subsequent divorce it is perhaps not surprising that these notes are no longer extant. The same applies to The Big Four, despite the fact that this episodic novel had appeared earlier as individual short stories. And there is nothing showing the genesis of the first adventure of Tommy and Tuppence in The Secret Adversary (1922); for the 1929 collection Partners in Crime, there are only sketchy notes. This is a particular disappointment as it might have given us an insight into the thoughts of Agatha Christie on her fellow crime writers, who are affectionately pastiched in this collection.

From the 1930s onwards, however, the only missing book titles are Murder on the Orient Express (1934), Cards on the Table (1936) and Murder is Easy (1939). This would seem to suggest that very few notebooks were, in fact, lost. Why notes for Murder is Easy are missing – apart from a passing reference in Notebook 66 – is a minor mystery when the notes for the novels on either side survive.

In some cases the notes are sketchy and consist of little more than a list of characters (Death on the Nile – Notebook 30). And some titles have copious notes: They Came to Baghdad (100 pages), Five Little Pigs (75 pages), One, Two, Buckle my Shoe (75 pages). Other titles outline the course of the finished book so closely that I am tempted to assume that there were earlier, rougher notes that have not survived. A case in point is Ten Little Niggers

(aka And Then There Were None). In An Autobiography Dame Agatha remembers: ‘I had written the book Ten Little Niggers because it was so difficult to do that the idea fascinated me. Ten people had to die without it becoming ridiculous or the murderer becoming obvious. I wrote the book after a tremendous amount of planning.’ Unfortunately, none of this planning survives; what there is in Notebook 65 follows almost exactly the progress of the novel. It is difficult to believe that this would have been written straight on to the page with so few deletions or so little discussion of possible alternatives. Nor are there, unfortunately, any notes for her dramatisation of this famous story. For the rest of her career we are fortunate to have notes on all of the novels. In the case of most of the later titles the notes are extensive and detailed – and legible.

Fewer than 50 of almost 150 short stories are discussed in the pages of the Notebooks. This may mean that, for many of them, Christie typed directly on to the page without making any preliminary notes. Or that she worked on loose pages that she subsequently discarded. When she wrote the early short stories she did not consider herself a writer in the professional sense of the word. It was only after her divorce, and the consequent need to earn her living, that she realised that writing was now her ‘job’. So the earliest adventures of Poirot as published in 1923 in The Sketch magazine do not appear in the Notebooks at all, although there are, thankfully, detailed notes for her greatest Poirot collection, The Labours of Hercules. And many ideas that she sketched for short stories did not make it any further than the pages of the Notebooks (see ‘Unused Ideas’ (#litres_trial_promo)).

Two examples of Agatha Christie, the housekeeper. The heading ‘Wallingford’ on the lower one confirms that they are both lists of items to bring to or from her various homes.

There are notes on most of her stage work, including unknown, unperformed and uncompleted plays. There are only two pages each of notes for her most famous and her greatest play, Three Blind Mice (as it still was at the time of writing the notes) and Witness for the Prosecution respectively. But these are disappointingly uninformative, as they contain no detail of the adaptation, merely a draft of scenes without any of the usual speculation.

And there are many pages devoted to An Autobiography, her poetry and her Westmacott novels. Most of the poetry is of a personal nature as she often wrote a poem as a birthday present for family members. There are only 40 pages in total devoted to the Westmacott titles, mainly of quotations that might provide titles, and those for An Autobiography are, for the most part, diffuse and disconnected, consisting of what are little more than reminders to herself.

… I usually have about half a dozen on hand …

It could reasonably be supposed that each Agatha Christie title has its own Notebook. This is emphatically not the case. In only five instances is a Notebook devoted to a single title. Notebooks 26 and 42 are entirely dedicated to Third Girl; Notebook 68 concerns only Peril at End House; Notebook 2 is A Caribbean Mystery; Notebook 46 contains nothing but extensive historical background and a rough outline for Death Comes as the End. Otherwise, every Notebook is a fascinating record of a productive brain and an industrious professional. Some examples should make this clear.

Notebook 53 contains:

Fifty pages of detailed notes for After the Funeral and A Pocket Full of Rye alternating with each other every few pages

Rough notes for Destination Unknown

A short outline of an unwritten novel

Three separate and different attempts at the radio play Personal Call

Notes for a new Mary Westmacott

Preliminary notes for Witness for the Prosecution and The Unexpected Guest

An outline for an unpublished and unperformed play, Miss Perry

Some poetry

Notebook 13 contains:

38 pages for Death Comes as the End

20 pages for Taken at the Flood

20 pages for Sparkling Cyanide

6 pages for Mary Westmacott

30 pages of a foreign Travel Diary

4 pages each for The Hollow, Curtain, N or M?

Notebook 35 contains:

75 pages for Five Little Pigs

75 pages for One, Two, Buckle my Shoe

8 pages for N or M?

4 pages for The Body in the Library

25 pages of ideas

… if I had kept all these things neatly sorted …

One of the most frustrating aspects of the Notebooks is the lack of order, especially the uncertainty of the chronology. Although there are 73 Notebooks, we have only 77 examples of dates most of them incomplete. A page can be headed ‘October 20th’ or ‘September 28th’ or just ‘1948’. There are only six examples of complete (day/month/year) dates all from the 1960s and 70s. In the case of incomplete dates it is sometimes possible to deduce the year from the publication date of the title in question, but in the case of notes for an unpublished or undeveloped idea, this is almost impossible. This uncertainty is compounded for a variety of reasons.

First, use of the Notebooks was utterly random. Christie opened a Notebook (or, as she says herself, any of half a dozen contemporaneous ones), found the next blank page and began to write. It was simply a case of finding an empty page, even one between two already filled pages. And, as if that wasn’t complicated enough, in almost all cases she turned the Notebook over and, with admirable economy, wrote from the back also. In one extreme case, during the plotting of ‘Manx Gold’ she even wrote sideways on the page! It should be remembered that many of these pages were filled during the days of paper rationing in the Second World War. In compiling this book I had to devise a system to enable me to identify whether or not the page was an ‘upside-down’ one.

Second, because many pages are filled with notes for stories that were never completed, there are no publication dates as a guideline. Deductions can sometimes be made from the notes immediately preceding and following, but this method is not entirely flawless. A closer look at the contents of Notebook 13 (listed above) illustrates an aspect of this random chronology. Leaving aside Curtain, the earliest novel listed here is N or M? published in 1941 and the latest is Taken at the Flood published in 1948. But many of the intervening titles are missing from this Notebook – Five Little Pigs is in Notebook 35, Evil under the Sun in Notebook 39 and Towards Zero in Notebook 32.

This page, in Notebook 66, is from Christie’s most prolific and ingenious period and list ideas that became Sad Cypress, ‘Problem at Sea’ and They Do It With Mirrors. It was one of very few pages in the Notebooks to bear a date, and the stories were published between 1936 and 1952.

Another rare page with a date, demonstrating a marked change in handwriting, these are among the last notes that Christie wrote and appear in Notebook 7. Although she continued making notes, no new material appeared later than Postern of Fate, published in October 1973.

Third, in many cases jottings for a book may have preceded publication by many years. The earliest notes for The Unexpected Guest are headed ‘1951’ in Notebook 31, i.e. seven years before the first performance; the germ of Endless Night first appears, six years before publication, on a page of Notebook 4 dated 1961.

The pages following a clearly dated page cannot be assumed to have been written at the same time. For example:

page 1 of Notebook 3 reads ‘General Projects 1955’

page 9 reads ‘Nov. 5th 1965’ (and there were ten books in the intervening period)

page 12 reads ‘1963’