По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

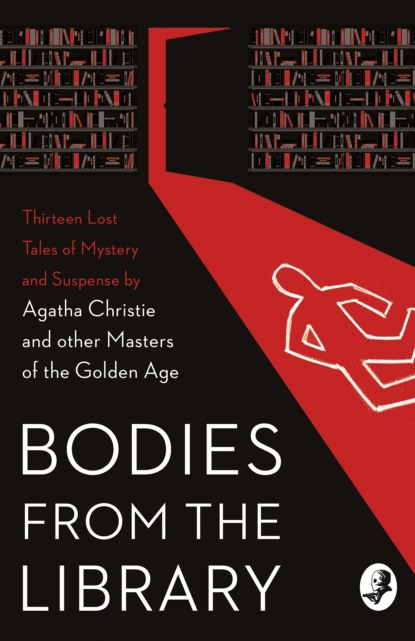

Bodies from the Library: Lost Tales of Mystery and Suspense by Agatha Christie and other Masters of the Golden Age

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

French took something from his pocket. ‘It’s not lost, sir. I think this is it. Yes: colour, shape, size and even thread are the same. And do you know where I found it? Gripped in Mr Marbeck’s fingers: I could hardly get it out.’

FREEMAN WILLS CROFTS (#ulink_385ae16d-3db0-5f2a-8460-8075a253a280)

Born in Dublin in 1879, Freeman Wills Crofts would go on to become one of Britain’s best loved writers of detective fiction. After leaving school, Crofts joined the Belfast and North Counties Railway, rising to Chief Assistant Engineer. In 1912 he married and, in his early 30s, wrote a novel during a long period of convalescence. In homage to Charles Dickens, this first attempt was entitled A Mystery of Two Cities but by the time it was published in June 1920, by Collins, it had been retitled The Cask after a rewrite that saw the final section of the novel, largely comprising a trial, excised altogether.

Fired by this success, Crofts wrote a second novel, The Ponson Case. And then a third … For his fifth novel, Inspector French’s Greatest Case, he created Joseph French, the Scotland Yard detective who would go on to appear in a total of thirty novels, countless radio plays and three stage plays. As Crofts described him, ‘Soapy Joe [is] an ordinary man, carrying out his work, in an ordinary way … He makes mistakes but goes ahead in spite of them.’

More books followed and Crofts was soon recognised as one of the best practitioners in the genre. The railway engineer and part-time organist and choirmaster retired in 1929 to take up writing full time, and in 1930 Crofts was invited by Anthony Berkeley to become a founding member of the Detection Club, based in London. Partly because of this, Crofts and his wife Mary moved to Blackheath, a pretty village in Surrey where their first home was a house, Wildern, which has since been re-named after its most famous owner. Over the next twenty years Crofts would produce many books including The Hog’s Back Mystery (1933), Crime at Guildford (1935) and The Affair at Little Wokeham (1943), all of which are set in Surrey.

An active member of the Detection Club, Crofts also contributed to several of their collaborative ventures, including the 1931 novel The Floating Admiral, which he wrote together with Agatha Christie and other members of the Detection Club. During the Second World War, Crofts produced dozens of radio plays for the BBC, many of which he later turned into short stories for the Inspector French collection Murderers Make Mistakes (1947). Throughout the war and in the years immediately afterwards, Crofts continued to write but his output gradually declined and he died in 1957 after a stubborn battle with cancer.

Croft’s obituarist in The Times praised the writer for his ‘logically contrived’ plots and his close attention to detail, especially in the construction and breaking down of superficially cast-iron alibis. Crofts’ novels often feature railway travel and the alibis of his criminals often turn on the complexities of pre-internet timetabling. His shorter fiction is similarly precise with the majority turning on what he would style ‘the usual tiny oversight’ or an inconsistency in a suspect’s statement so that they offer the reader an opportunity to outwit the criminal before French.

Sixty years after his death, the work of Freeman Wills Crofts is having something of a resurgence. Several of his novels are once again in print and a celebratory collection is in preparation bringing together previously uncollected short stories and some of his unpublished stage and radio plays.

‘Dark Waters’ was first published in the London Evening Standard on 21 September 1953.

LINCKES’ GREAT CASE

Georgette Heyer

I

The chief paused and glanced sharply across the table to where Roger Linckes sat facing him, listening to his discourse.

‘It is a big job,’ Masters said abruptly. ‘So much is at stake. It’s not like some stage robbery, where Lady So-and-So’s pearls are stolen. It’s—well, the whole country—perhaps all Europe—is implicated. Maybe I’m wrong to set you on to it. You’re very young; you’ve had very little experience.’

The younger man flushed slightly under his tan.

‘I know, sir.’

Masters looked him over thoughtfully, from his grave young eyes to his brogued shoes. He smiled a little.

‘Anyhow, right or wrong, I’m going to let you see what you can do. I must admit I haven’t much hope. Where Tiffrus and Pollern have failed, a comparative tyro isn’t likely to succeed. But you did exceedingly well over that Panton affair, and it’s just possible you might hit on a solution to this mystery.’ He drummed on the table, frowning. ‘I’ve known it happen before. I suppose the big detectives get stale, or something approaching it. Let’s hope you’ll bring fresh ideas into the business. How much do you know about it?’

Linckes crossed his legs, clasping his hands about one knee.

‘Precious little, sir. You’ve seen to that, haven’t you? Nothing known to the papers, I mean. All I know is that there’s a leak in the Cabinet. Knowledge of our doings is being sold to Russia and to Germany. You say it has been going on for some time. The Soviet got wind of our new submarines. Hardly anyone in England knew about ’em, and yet Russia discovered the secret! Someone must have duplicated the plans and sold them—probably he’s done it many times before—and that someone must be one of those in the small circle of people who knew all the details of the new subs. In fact, he must have been a pretty big man. It only remains for us to find out which one.’

‘Very easy,’ Masters grunted. ‘It might have been a secretary.’

‘It might,’ conceded Linckes.

‘You don’t think so?’

‘I don’t know. It doesn’t seem likely. Who was in that circle?’

‘The Government knew all about the submarines,’ Masters answered. ‘But the actual plans at the time of the betrayal had been seen only by Caryu, the Secretary for War, Winthrop, the Under-Secretary, and Johnson for the Admiralty, and the inventor, of course, Sir Duncan Tassel. That rather dishes your theory, doesn’t it? Naturally, Tassel is above suspicion; so is Caryu; so are the other two.’

‘Are you sure that no one else knew of the plans?’

‘No, I’m not sure. I’m convinced that someone else did know—must have known. Winthrop swears no one could have known, but he can’t supply a counter-theory. He’s more or less running the investigation, you know.’

‘What does he say?’

‘He’s terribly worried, of course. We thought at first that his secretary was the man, but we can’t find the slightest grounds for suspicion against him, and Winthrop’s had him in his employ for years. It’s the greatest mystery I’ve struck yet. We’ve been working to discover the betrayer for months, and we’re no nearer a solution now than we were when we began. And still it goes on. Take the affair of the negotiations with Carmania. They leaked into Russia, we know. Or take the case of the submarines. Those plans weren’t stolen, they were just copied. The only person, seemingly, who could have done it, was Winthrop. He alone knows the secret of Caryu’s safe. The plans were with Caryu for three days. All the rest of the time they were with Tassel, and they never left him for a moment. The thing must have been done during those three days that they were in Caryu’s safe, because before that date they were incomplete, and dates show that they can’t have been copied after they were returned to Fothermere. Now, having whittled the date down to three days, how much nearer the solution are we? Of course, everything points to Winthrop.’

‘Or Caryu,’ said Linckes quietly.

‘My good youth, are you seriously accusing Mr Caryu? Even supposing that he is the man we’re after—which he isn’t—would he have copied the plans while they were in his house? He’s not a fool, you know.’

‘Where was he during those three days?’

‘At home. Winthrop went round to his house, and together they examined the plans. That was on the first day, and Winthrop left the house soon after nine in the evening. Shortly after he had gone Caryu put the plans into his safe. He had them with him next day at the War Office, and put them into the safe when he came home. Not even his secretary knew of their existence. They were returned to Tassel on the following afternoon.’

Linckes’ forehead wrinkled in perplexity.

‘When did Johnson see them?’

‘Before. He worked with Tassel, you see.’

‘Um! And where did Sir Charles Winthrop go when he left Caryu’s house that night?’

‘He went straight down to his place in the country—Millbank. Took Max Lawson with him. He was there for the rest of the week, with a small house-party. That wipes him off the list.’

‘What sort of a man is he?’ Linckes asked. ‘All I know is that he’s fairly young, very clever, and good-looking, rich, and an orphan.’

‘He’s an awfully decent chap. Everybody likes him. Son of old Mortimer Winthrop, the railwayman. Mortimer separated from his wife when Charles was a kid. You know Charles’ history. She went abroad with the other child, I believe, and Mortimer kept Charles. Did awfully well in the Secret Service during the war, and rose like a rocket. He’ll be a big man before long, if this awful business is cleared up. Of course, he feels pretty badly about it. Means he’ll perhaps have to resign his post.’

‘Yes, I suppose so. What about Tassel?’

‘Tassel? My dear Linckes, if you’re going to shadow him I shall begin to regret I ever put you on to the case. Why, you might just as well suspect Caryu!’

‘Ah!’ said Linckes, and saw the chief’s lips twitch.

The telephone-bell rang sharply before Masters had time to speak again. He unhooked the receiver.

‘Hallo! What? Sir Charles? Yes, put him through to me at once, will you?’ He nodded at Linckes. ‘I thought Winthrop would ring up. I told him about you. Our White Hope. Yes? Hallo! Is that Sir Charles? Good morning! Yes, he’s here now. Yes, I’ve told him all I know. No. I don’t think so. Well, he hasn’t had much chance to yet. What? Yes, certainly! Now? All right, Sir Charles, I’ll send him along. What! Oh, I see! Yes, all right. Goodbye!’

He put the receiver back.

‘Sir Charles wants you to go along to his house now, Linckes—16, Arlington Street. Get along there as quickly as you can, will you? I want you to put every ounce of your brain into this. It’s a big chance for you, you know.’

Linckes rose, and drew a deep breath.

II

Half an hour later he stood in the library of No. 16, Arlington Street, taking in his surroundings with appreciative eyes. He was examining a fine old chest by the window when Winthrop came in.