По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

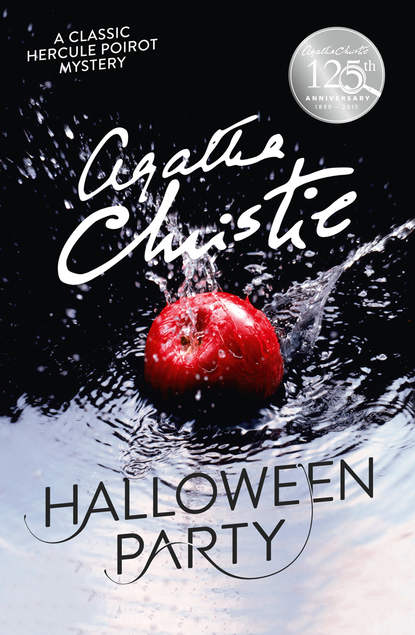

Hallowe’en Party

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Tell me,’ said Poirot.

‘That’s what I’ve come for. But now I’ve got here, it’s so difficult because I don’t know where to begin.’

‘At the beginning?’ suggested Poirot, ‘or is that too conventional a way of acting?’

‘I don’t know when the beginning was. Not really. It could have been a long time ago, you know.’

‘Calm yourself,’ said Poirot. ‘Gather together the various threads of this matter in your mind and tell me. What is it that has so upset you?’

‘It would have upset you, too,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘At least, I suppose it would.’ She looked rather doubtful. ‘One doesn’t know, really, what does upset you. You take so many things with a lot of calm.’

‘It is often the best way,’ said Poirot.

‘All right,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘It began with a party.’

‘Ah yes,’ said Poirot, relieved to have something as ordinary and sane as a party presented to him. ‘A party. You went to a party and something happened.’

‘Do you know what a Hallowe’en party is?’ said Mrs Oliver.

‘I know what Hallowe’en is,’ said Poirot. ‘The 31st of October.’ He twinkled slightly as he said, ‘When witches ride on broomsticks.’

‘There were broomsticks,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘They gave prizes for them.’

‘Prizes?’

‘Yes, for who brought the best decorated ones.’

Poirot looked at her rather doubtfully. Originally relieved at the mention of a party, he now again felt slightly doubtful. Since he knew that Mrs Oliver did not partake of spirituous liquor, he could not make one of the assumptions that he might have made in any other case.

‘A children’s party,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘Or rather, an eleven-plus party.’

‘Eleven-plus?’

‘Well, that’s what they used to call it, you know, in schools. I mean they see how bright you are, and if you’re bright enough to pass your eleven-plus, you go on to a grammar school or something. But if you’re not bright enough, you go to something called a Secondary Modern. A silly name. It doesn’t seem to mean anything.’

‘I do not, I confess, really understand what you are talking about,’ said Poirot. They seemed to have got away from parties and entered into the realms of education.

Mrs Oliver took a deep breath and began again.

‘It started really,’ she said, ‘with the apples.’

‘Ah yes,’ said Poirot, ‘it would. It always might with you, mightn’t it?’

He was thinking to himself of a small car on a hill and a large woman getting out of it, and a bag of apples breaking, and the apples running and cascading down the hill.

‘Yes,’ he said encouragingly, ‘apples.’

‘Bobbing for apples,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘That’s one of the things you do at a Hallowe’en party.’

‘Ah yes, I think I have heard of that, yes.’

‘You see, all sorts of things were being done. There was bobbing for apples, and cutting sixpence off a tumblerful of flour, and looking in a looking-glass—’

‘To see your true love’s face?’ suggested Poirot knowledgeably.

‘Ah,’ said Mrs Oliver, ‘you’re beginning to understand at last.’

‘A lot of old folklore, in fact,’ said Poirot, ‘and this all took place at your party.’

‘Yes, it was all a great success. It finished up with Snapdragon. You know, burning raisins in a great dish. I suppose—’ her voice faltered, ‘—I suppose that must be the actual time when it was done.’

‘When what was done?’

‘A murder. After the Snapdragon everyone went home,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘That, you see, was when they couldn’t find her.’

‘Find whom?’

‘A girl. A girl called Joyce. Everyone called her name and looked around and asked if she’d gone home with anyone else, and her mother got rather annoyed and said that Joyce must have felt tired or ill or something and gone off by herself, and that it was very thoughtless of her not to leave word. All the sort of things that mothers say when things like that happen. But anyway, we couldn’t find Joyce.’

‘And had she gone home by herself?’

‘No,’ said Mrs Oliver, ‘she hadn’t gone home…’ Her voice faltered. ‘We found her in the end—in the library. That’s where—where someone did it, you know. Bobbing for apples. The bucket was there. A big, galvanized bucket. They wouldn’t have the plastic one. Perhaps if they’d had the plastic one it wouldn’t have happened. It wouldn’t have been heavy enough. It might have tipped over—’

‘What happened?’ said Poirot. His voice was sharp.

‘That’s where she was found,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘Someone, you know, someone had shoved her head down into the water with the apples. Shoved her down and held her there so that she was dead, of course. Drowned. Drowned. Just in a galvanized iron bucket nearly full of water. Kneeling there, sticking her head down to bob at an apple. I hate apples,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘I never want to see an apple again.’

Poirot looked at her. He stretched out a hand and filled a small glass with cognac.

‘Drink this,’ he said. ‘It will do you good.’

CHAPTER 4 (#u7e53bd08-a18a-5977-a9af-7d44e346540a)

Mrs Oliver put down the glass and wiped her lips.

‘You were right,’ she said. ‘That—that helped. I was getting hysterical.’

‘You have had a great shock, I see now. When did this happen?’

‘Last night. Was it only last night? Yes, yes, of course.’

‘And you came to me.’

It was not a quite a question, but it displayed a desire for more information than Poirot had yet had.

‘You came to me—why?’

‘I thought you could help,’ said Mrs Oliver. ‘You see, it’s—it’s not simple.’