По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

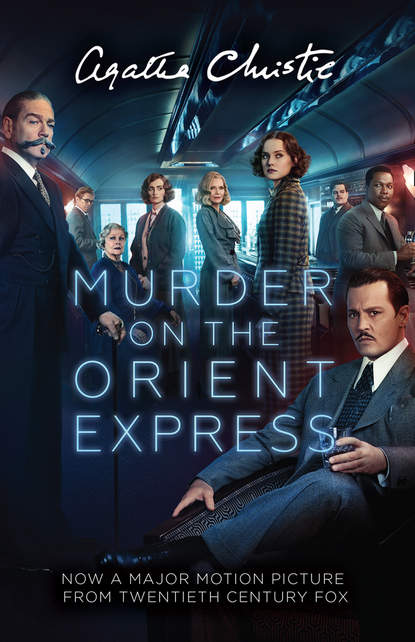

Murder on the Orient Express

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘All the same, you must find room for this gentleman here. He is a friend of mine. He can have the No. 16.’

‘It is taken, Monsieur.’

‘What? The No. 16?’

A glance of understanding passed between them, and the conductor smiled. He was a tall, sallow man of middle age.

‘But yes, Monsieur. As I told you, we are full—full—everywhere.’

‘But what passes itself?’ demanded M. Bouc angrily. ‘There is a conference somewhere? It is a party?’

‘No, Monsieur. It is only chance. It just happens that many people have elected to travel tonight.’

M. Bouc made a clicking sound of annoyance.

‘At Belgrade,’ he said, ‘there will be the slip coach from Athens. There will also be the Bucharest-Paris coach—but we do not reach Belgrade until tomorrow evening. The problem is for tonight. There is no second-class berth free?’

‘There is a second-class berth, Monsieur—’

‘Well, then—’

‘But it is a lady’s berth. There is already a German woman in the compartment—a lady’s-maid.’

‘Là, là, that is awkward,’ said M. Bouc.

‘Do not distress yourself, my friend,’ said Poirot. ‘I must travel in an ordinary carriage.’

‘Not at all. Not at all.’ He turned once more to the conductor. ‘Everyone has arrived?’

‘It is true,’ said the man, ‘that there is one passenger who has not yet arrived.’

He spoke slowly with hesitation.

‘But speak then?’

‘No. 7 berth—a second-class. The gentleman has not yet come, and it is four minutes to nine.’

‘Who is it?’

‘An Englishman,’ the conductor consulted his list. ‘A M. Harris.’

‘A name of good omen,’ said Poirot. ‘I read my Dickens. M. Harris, he will not arrive.’

‘Put Monsieur’s luggage in No. 7,’ said M. Bouc. ‘If this M. Harris arrives we will tell him that he is too late—that berths cannot be retained so long—we will arrange the matter one way or another. What do I care for a M. Harris?’

‘As Monsieur pleases,’ said the conductor.

He spoke to Poirot’s porter, directing him where to go.

Then he stood aside the steps to let Poirot enter the train. ‘Tout à fait au bout, Monsieur,’ he called. ‘The end compartment but one.’

Poirot passed along the corridor, a somewhat slow progress, as most of the people travelling were standing outside their carriages.

His polite ‘Pardons’ were uttered with the regularity of clockwork. At last he reached the compartment indicated. Inside it, reaching up to a suitcase, was the tall young American of the Tokatlian.

He frowned as Poirot entered.

‘Excuse me,’ he said. ‘I think you’ve made a mistake.’ Then, laboriously in French, ‘Je crois que vous avez un erreur.’

Poirot replied in English.

‘You are Mr Harris?’

‘No, my name is MacQueen. I—’

But at that moment the voice of the Wagon Lit conductor spoke from over Poirot’s shoulder. An apologetic, rather breathless voice.

‘There is no other berth on the train, Monsieur. The gentleman has to come in here.’

He was hauling up the corridor window as he spoke and began to lift in Poirot’s luggage.

Poirot noticed the apology in his tone with some amusement. Doubtless the man had been promised a good tip if he could keep the compartment for the sole use of the other traveller. However, even the most munificent of tips lose their effect when a director of the company is on board and issues his orders.

The conductor emerged from the compartment, having swung the suit-cases up on to the racks.

‘Voilà Monsieur,’ he said. ‘All is arranged. Yours is the upper berth, the number 7. We start in one minute.’

He hurried off down the corridor. Poirot re-entered the compartment.

‘A phenomenon I have seldom seen,’ he said cheerfully. ‘A Wagon Lit conductor himself puts up the luggage! It is unheard of!’

His fellow traveller smiled. He had evidently got over his annoyance—had probably decided that it was no good to take the matter other than philosophically.

‘The train’s remarkably full,’ he said.

A whistle blew, there was a long, melancholy cry from the engine. Both men stepped out into the corridor.

Outside a voice shouted.

‘En voiture.’

‘We’re off,’ said MacQueen.

But they were not quite off. The whistle blew again.

‘I say, sir,’ said the young man suddenly, ‘if you’d rather have the lower berth—easier, and all that—well, that’s all right by me.’

‘No, no,’ protested Poirot. ‘I would not deprive you—’