По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

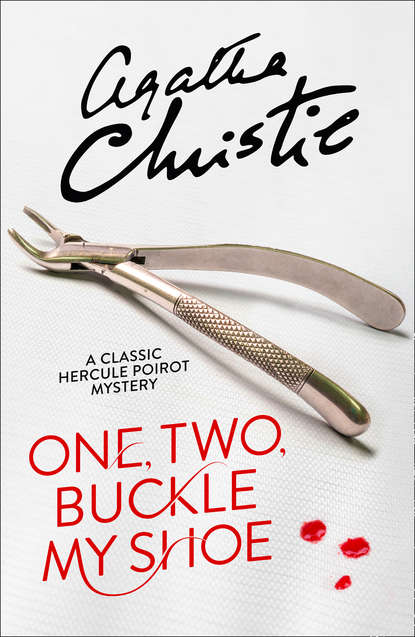

One, Two, Buckle My Shoe

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Exactly. The medical evidence agrees with that for what it’s worth. The divisional surgeon examined the body—at twenty past two. He wouldn’t commit himself—they never do nowadays—too many individual idiosyncrasies, they say. But Morley couldn’t have been shot later than one o’clock, he says—probably considerably earlier—but he wouldn’t be definite.’

Poirot said thoughtfully:

‘Then at twenty-five minutes past twelve our dentist is a normal dentist, cheerful, urbane, competent. And after that? Despair—misery—what you will—and he shoots himself?’

‘It’s funny,’ said Japp. ‘You’ve got to admit, it’s funny.’

‘Funny,’ said Poirot, ‘is not the word.’

‘I know it isn’t really—but it’s the sort of thing one says. It’s odd, then, if you like that better.’

‘Was it his own pistol?’

‘No, it wasn’t. He hadn’t got a pistol. Never had had one. According to his sister there wasn’t such a thing in the house. There isn’t in most houses. Of course he might have bought it if he’d made up his mind to do away with himself. If so, we’ll soon know about it.’

Poirot asked:

‘Is there anything else that worries you?’

Japp rubbed his nose.

‘Well, there was the way he was lying. I wouldn’t say a man couldn’t fall like that—but it wasn’t quite right somehow! And there was just a trace or two on the carpet—as though something had been dragged along it.’

‘That, then, is decidedly suggestive.’

‘Yes, unless it was that dratted boy. I’ve a feeling that he may have tried to move Morley when he found him. He denies it, of course, but then he was scared. He’s that kind of young ass. The kind that’s always putting their foot in it and getting cursed, and so they come to lie about things almost automatically.’

Poirot looked thoughtfully round the room.

At the wash-basin on the wall behind the door, at the tall filing cabinet on the other side of the door. At the dental chair and surrounding apparatus near the window, then along to the fireplace and back to where the body lay; there was a second door in the wall near the fireplace.

Japp had followed his glance. ‘Just a small office through there.’ He flung open the door.

It was as he had said, a small room, with a desk, a table with a spirit lamp and tea apparatus and some chairs. There was no other door.

‘This is where his secretary worked,’ explained Japp. ‘Miss Nevill. It seems she’s away today.’

His eyes met Poirot’s. The latter said:

‘He told me, I remember. That again—might be a point against suicide?’

‘You mean she was got out of the way?’

Japp paused. He said:

‘If it wasn’t suicide, he was murdered. But why? That solution seems almost as unlikely as the other. He seems to have been a quiet, inoffensive sort of chap. Who would want to murder him?’

Poirot said:

‘Who could have murdered him?’

Japp said:

‘The answer to that is—almost anybody! His sister could have come down from their flat above and shot him, one of the servants could have come in and shot him. His partner, Reilly, could have shot him. The boy Alfred could have shot him. One of the patients could have shot him.’ He paused and said, ‘And Amberiotis could have shot him—easiest of the lot.’

Poirot nodded.

‘But in that case—we have to find out why.’

‘Exactly. You’ve come round again to the original problem. Why? Amberiotis is staying at the Savoy. Why does a rich Greek want to come and shoot an inoffensive dentist?’

‘That’s really going to be our stumbling block. Motive!’

Poirot shrugged his shoulders. He said:

‘It would seem that death selected, most inartistically, the wrong man. The Mysterious Greek, the Rich Banker, the Famous Detective—how natural that one of them should be shot! For mysterious foreigners may be mixed up in espionage and rich bankers have connections who will benefit by their deaths and famous detectives may be dangerous to criminals.’

‘Whereas poor old Morley wasn’t dangerous to anybody,’ observed Japp gloomily.

‘I wonder.’

Japp whirled round on him.

‘What’s up your sleeve now?’

‘Nothing. A chance remark.’

He repeated to Japp those few casual words of Mr Morley’s about recognizing faces, and his mention of a patient.

Japp looked doubtful.

‘It’s possible, I suppose. But it’s a bit far-fetched. It might have been someone who wanted their identity kept dark. You didn’t notice any of the other patients this morning?’

Poirot murmured:

‘I noticed in the waiting-room a young man who looked exactly like a murderer!’

Japp said, startled: ‘What’s that?’

Poirot smiled:

‘Mon cher, it was upon my arrival here! I was nervous, fanciful—enfin, in a mood. Everything seemed sinister to me, the waiting-room, the patients, the very carpet on the stairs! Actually, I think the young man had very bad toothache. That was all!’

‘I know what it can be,’ said Japp. ‘However, we’ll check up on your murderer all the same. We’ll check up on everybody, whether it’s suicide or not. I think the first thing is to have another talk with Miss Morley. I’ve only had a word or two. It was a shock to her, of course, but she’s the kind that doesn’t break down. We’ll go and see her now.’

Tall and grim, Georgina Morley listened to what the two men had said and answered their questions. She said with emphasis:

‘It’s incredible to me—quite incredible—that my brother should have committed suicide!’