По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

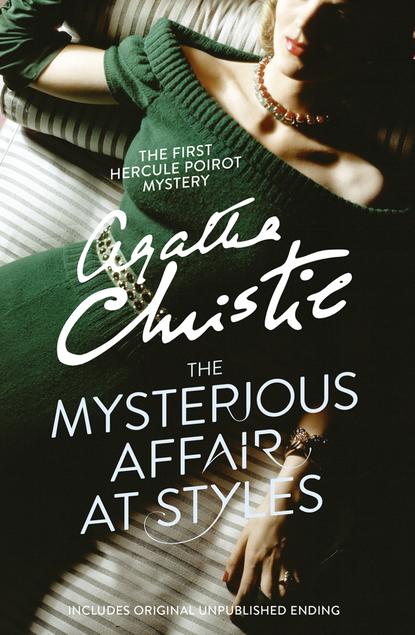

The Mysterious Affair at Styles

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Yes, sir, but that’s always bolted. It’s never been undone.’

‘Well, we might just see.’

He ran rapidly down the corridor to Cynthia’s room. Mary Cavendish was there, shaking the girl—who must have been an unusually sound sleeper—and trying to wake her.

In a moment or two he was back.

‘No good. That’s bolted too. We must break in the door. I think this one is a shade less solid than the one in the passage.’

We strained and heaved together. The framework of the door was solid, and for a long time it resisted our efforts, but at last we felt it give beneath our weight, and finally, with a resounding crash, it was burst open.

We stumbled in together, Lawrence still holding his candle. Mrs Inglethorp was lying on the bed, her whole form agitated by violent convulsions, in one of which she must have overturned the table beside her. As we entered, however, her limbs relaxed, and she fell back upon the pillows.

John strode across the room and lit the gas. Turning to Annie, one of the housemaids, he sent her downstairs to the dining room for brandy. Then he went across to his mother whilst I unbolted the door that gave on the corridor.

I turned to Lawrence, to suggest that I had better leave them now that there was no further need of my services, but the words were frozen on my lips. Never have I seen such a ghastly look on any man’s face. He was white as chalk, the candle he held in his shaking hand was sputtering onto the carpet, and his eyes, petrified with terror, or some such kindred emotion, stared fixedly over my head at a point on the further wall. It was as though he had seen something that turned him to stone. I instinctively followed the direction of his eyes, but I could see nothing unusual. The still feebly flickering ashes in the grate, and the row of prim ornaments on the mantelpiece, were surely harmless enough.

The violence of Mrs Inglethorp’s attack seemed to be passing. She was able to speak in short gasps.

‘Better now—very sudden—stupid of me—to lock myself in.’

A shadow fell on the bed and, looking up, I saw Mary Cavendish standing near the door with her arm around Cynthia. She seemed to be supporting the girl, who looked utterly dazed and unlike herself. Her face was heavily flushed, and she yawned repeatedly.

‘Poor Cynthia is quite frightened,’ said Mrs Cavendish in a low clear voice. She herself, I noticed, was dressed in her white land smock. Then it must be later than I thought. I saw that a faint streak of daylight was showing through the curtains of the windows, and that the clock on the mantelpiece pointed to close upon five o’clock.

A strangled cry from the bed startled me. A fresh access of pain seized the unfortunate old lady. The convulsions were of a violence terrible to behold. Everything was confusion. We thronged round her, powerless to help or alleviate. A final convulsion lifted her from the bed, until she appeared to rest upon her head and her heels, with her body arched in an extraordinary manner. In vain Mary and John tried to administer more brandy. The moments flew. Again the body arched itself in that peculiar fashion.

At that moment, Dr Bauerstein pushed his way authoritatively into the room. For one instant he stopped dead, staring at the figure on the bed, and, at the same instant, Mrs Inglethorp cried out in a strangled voice, her eyes fixed on the doctor:

‘Alfred—Alfred—’ Then she fell back motionless on the pillows.

With a stride, the doctor reached the bed, and seizing her arms worked them energetically, applying what I knew to be artificial respiration. He issued a few short sharp orders to the servants. An imperious wave of his hand drove us all to the door. We watched him, fascinated, though I think we all knew in our hearts that it was too late, and that nothing could be done now. I could see by the expression on his face that he himself had little hope.

Finally he abandoned his task, shaking his head gravely. At that moment, we heard footsteps outside, and Dr Wilkins, Mrs Inglethorp’s own doctor, a portly, fussy little man, came bustling in.

In a few words Dr Bauerstein explained how he had happened to be passing the lodge gates as the car came out, and had run up to the house as fast as he could, whilst the car went on to fetch Dr Wilkins. With a faint gesture of the hand, he indicated the figure on the bed.

‘Ve–ry sad. Ve–ry sad,’ murmured Dr Wilkins. ‘Poor dear lady. Always did far too much—far too much—against my advice. I warned her. Her heart was far from strong. ‘Take it easy,’ said to her, ‘Take—it—easy.’ But no—her zeal for good works was too great. Nature rebelled. Na–ture—re–belled.’

Dr Bauerstein, I noticed, was watching the local doctor narrowly. He still kept his eyes fixed on him as he spoke.

‘The convulsions were of a peculiar violence, Dr Wilkins. I am sorry you were not here in time to witness them. They were quite—tetanic in character.’

‘Ah!’ said Dr Wilkins wisely.

‘I should like to speak to you in private,’ said Dr Bauerstein. He turned to John. ‘You do not object?’

‘Certainly not.’

We all trooped out into the corridor, leaving the two doctors alone, and I heard the key turned in the lock behind us.

We went slowly down the stairs. I was violently excited. I have a certain talent for deduction, and Dr Bauerstein’s manner had started a flock of wild surmises in my mind. Mary Cavendish laid her hand upon my arm.

‘What is it? Why did Dr Bauerstein seem so—peculiar?’

I looked at her.

‘Do you know what I think?’

‘What?’

‘Listen!’ I looked round, the others were out of earshot. I lowered my voice to a whisper. ‘I believe she has been poisoned! I’m certain Dr Bauerstein suspects it.’

‘What?’ She shrank against the wall, the pupils of her eyes dilating wildly. Then, with a sudden cry that startled me, she cried out: ‘No, no—not that—not that!’ And breaking from me, fled up the stairs. I followed her, afraid that she was going to faint. I found her leaning against the banisters, deadly pale. She waved me away impatiently.

‘No, no—leave me. I’d rather be alone. Let me just be quiet for a minute or two. Go down to the others.’

I obeyed her reluctantly. John and Lawrence were in the dining room. I joined them. We were all silent, but I suppose I voiced the thoughts of us all when I at last broke it by saying:

‘Where is Mr Inglethorp?’

John shook his head.

‘He’s not in the house.’

Our eyes met. Where was Alfred Inglethorp? His absence was strange and inexplicable. I remembered Mrs Inglethorp’s dying words. What lay beneath them? What more could she have told us, if she had had time?

At last we heard the doctors descending the stairs. Dr Wilkins was looking important and excited, and trying to conceal an inward exultation under a manner of decorous calm. Dr Bauerstein remained in the background, his grave bearded face unchanged. Dr Wilkins was the spokesman for the two. He addressed himself to John:

‘Mr Cavendish, I should like your consent to a post-mortem.’

‘Is that necessary?’ asked John gravely. A spasm of pain crossed his face.

‘Absolutely,’ said Dr Bauerstein.

‘You mean by that—?’

‘That neither Dr Wilkins nor myself could give a death certificate under the circumstances.’

John bent his head.

‘In that case, I have no alternative but to agree.’

‘Thank you,’ said Dr Wilkins briskly. ‘We propose that it should take place tomorrow night—or rather tonight.’ And he glanced at the daylight. ‘Under the circumstances, I am afraid an inquest can hardly be avoided—these formalities are necessary, but I beg that you won’t distress yourselves.’

There was a pause, and then Dr Bauerstein drew two keys from his pocket, and handed them to John.

‘These are the keys of the two rooms. I have locked them and, in my opinion, they would be better kept locked for the present.’