По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

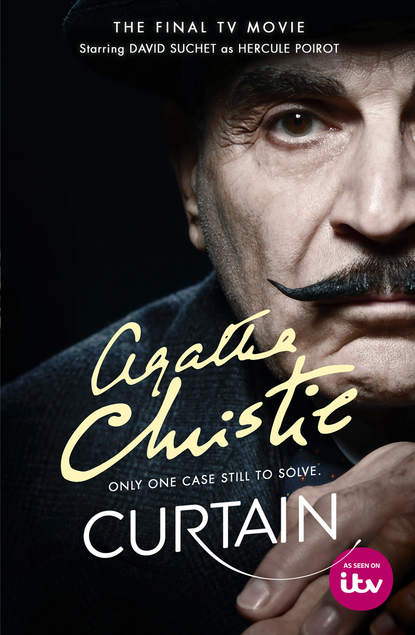

Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He turned to her eagerly and broke in. ‘Yes, yes. I say, if you don’t mind, let’s go down to the lab. I’d like to be quite sure –’

Still talking, they went out of the room together. Barbara Franklin lay back on her pillows. She sighed. Nurse Craven said suddenly and rather disagreeably: ‘It’s Miss Hastings who’s the slave-driver, I think!’

Again Mrs Franklin sighed. She murmured: ‘I feel so inadequate. I ought, I know, to take more interest in John’s work, but I just can’t do it. I dare say it’s something wrong in me, but –’

She was interrupted by a snort from Boyd Carrington who was standing by the fireplace.

‘Nonsense, Babs,’ he said. ‘You’re all right. Don’t worry yourself.’

‘Oh but, Bill, dear, I do worry. I get so discouraged about myself. It’s all – I can’t help feeling it – it’s all so nasty. The guinea pigs and the rats and everything. Ugh!’ She shuddered. ‘I know it’s stupid, but I’m such a fool. It makes me feel quite sick. I just want to think of all the lovely happy things – birds and flowers and children playing. You know, Bill.’

He came over and took the hand she held out to him so pleadingly. His face as he looked down at her was changed, as gentle as any woman’s. It was, somehow, impressive – for Boyd Carrington was so essentially a manly man.

‘You’ve not changed much since you were seventeen, Babs,’ he said. ‘Do you remember that garden house of yours and the bird bath and the coconuts?’

He turned his head to me. ‘Barbara and I are old playmates,’ he said.

‘Old playmates!’ she protested.

‘Oh, I’m not denying that you’re over fifteen years younger than I am. But I played with you as a tiny tot when I was a young man. Gave you pick-a-backs, my dear. And then later I came home to find you a beautiful young lady – just on the point of making your début in the world – and I did my share by taking you out on the golf links and teaching you to play golf. Do you remember?’

‘Oh, Bill, do you think I’d forget?’

‘My people used to live in this part of the world,’ she explained to me. ‘And Bill used to come and stay with his old uncle, Sir Everard, at Knatton.’

‘And what a mausoleum it was – and is,’ said Boyd Carrington. ‘Sometimes I despair of getting the place liveable.’

‘Oh, Bill, it could be made marvellous – quite marvellous!’

‘Yes, Babs, but the trouble is I’ve got no ideas. Baths and some really comfortable chairs – that’s all I can think of. It needs a woman.’

‘I’ve told you I’ll come and help. I mean it. Really.’

Sir William looked doubtfully towards Nurse Craven. ‘If you’re strong enough, I could drive you over. What do you think, Nurse?’

‘Oh yes, Sir William. I really think it would do Mrs Franklin good – if she’s careful not to overtire herself, of course.’

‘That’s a date, then,’ said Boyd Carrington. ‘And now you have a good night’s sleep. Get into good fettle for tomorrow.’

We both wished Mrs Franklin good night and went out together. As we went down the stairs, Boyd Carrington said gruffly: ‘You’ve no idea what a lovely creature she was at seventeen. I was home from Burma – my wife died out there, you know. Don’t mind telling you I completely lost my heart to her. She married Franklin three or four years afterwards. Don’t think it’s been a happy marriage. It’s my idea that that’s what lies at the bottom of her ill health. Fellow doesn’t understand her or appreciate her. And she’s the sensitive kind. I’ve an idea that this delicacy of hers is partly nervous. Take her out of herself, amuse her, interest her, and she looks a different creature! But that damned sawbones only takes an interest in test tubes and West African natives and cultures.’ He snorted angrily.

I thought that there was, perhaps, something in what he said. Yet it surprised me that Boyd Carrington should be attracted by Mrs Franklin who, when all was said and done, was a sickly creature, though pretty in a frail, chocolate-box way. But Boyd Carrington himself was so full of vitality and life that I should have thought he would merely have been impatient with the neurotic type of invalid. However, Barbara Franklin must have been quite lovely as a girl, and with many men, especially those of the idealistic type such as I judged Boyd Carrington to be, early impressions die hard.

Downstairs, Mrs Luttrell pounced upon us and suggested bridge. I excused myself on the plea of wanting to join Poirot.

I found my friend in bed. Curtiss was moving around the room tidying up, but he presently went out, shutting the door behind him.

‘Confound you, Poirot,’ I said. ‘You and your infernal habit of keeping things up your sleeve. I’ve spent the whole evening trying to spot X.’

‘That must have made you somewhat distrait,’ observed my friend. ‘Did nobody comment on your abstraction and ask you what was the matter?’

I reddened slightly, remembering Judith’s questions. Poirot, I think, observed my discomfiture. I noticed a small malicious smile on his lips. He merely said, however: ‘And what conclusion have you come to on that point?’

‘Would you tell me if I was right?’

‘Certainly not.’

I watched his face closely.

‘I had considered Norton –’

Poirot’s face did not change.

‘Not,’ I said, ‘that I’ve anything to go upon. He just struck me as perhaps less unlikely than anyone else. And then he’s – well – inconspicuous. I should imagine the kind of murderer we’re after would have to be inconspicuous.’

‘That is true. But there are more ways than you think of being inconspicuous.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Supposing, to take a hypothetical case, that if a sinister stranger arrives there some weeks before the murder, for no apparent reason, he will be noticeable. It would be better, would it not, if the stranger were to be a negligible personality, engaged in some harmless sport like fishing.’

‘Or watching birds,’ I agreed. ‘Yes, but that’s just what I was saying.’

‘On the other hand,’ said Poirot, ‘it might be better still if the murderer were already a prominent personality – that is to say, he might be the butcher. That would have the further advantage that no one notices bloodstains on a butcher!’

‘You’re just being ridiculous. Everybody would know if the butcher had quarrelled with the baker.’

‘Not if the butcher had become a butcher simply in order to have a chance of murdering the baker. One must always look one step behind, my friend.’

I looked at him closely, trying to decide if a hint lay concealed in those words. If they meant anything definite, they would seem to point to Colonel Luttrell. Had he deliberately opened a guest house in order to have an opportunity of murdering one of the guests?

Poirot very gently shook his head. He said: ‘It is not from my face that you will get the answer.’

‘You really are a maddening fellow, Poirot,’ I said with a sigh. ‘Anyway, Norton isn’t my only suspect. What about this fellow Allerton?’

Poirot, his face still impassive, enquired: ‘You do not like him?’

‘No, I don’t.’

‘Ah. What you call the nasty bit of goods. That is right, is it not?’

‘Definitely. Don’t you think so?’

‘Certainly. He is a man,’ said Poirot slowly, ‘very attractive to women.’

I made an exclamation of contempt. ‘How women can be so foolish. What do they see in a fellow like that?’

‘Who can say? But it is always so. The mauvais sujet – always women are attracted to him.’