По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

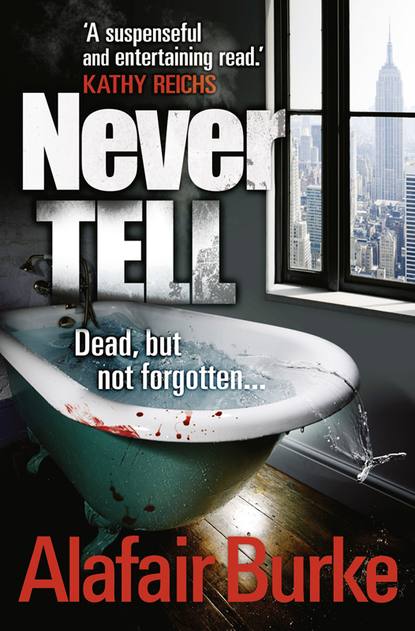

Never Tell

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I knew her. I mean, only through Ramona, and not like the two of them, but, yeah, sure, um, I’d say we all knew each other.”

“Julia’s mother mentioned meeting you one time at the townhouse. Did you go there often?”

Casey raised his eyebrows in surprise. “I can’t believe I even registered on that woman’s radar. Oh, wait, let me guess? She didn’t remember me at all. Just some homeless kid?”

“I think ‘from the streets’ may have been her phrase of choice. She said there were a few kids over that day.” She had mentioned two boys and a girl, to be exact.

“Yeah, I think it was Brandon, and this girl we see at the park sometimes named Vonda.”

“Did you go to Julia’s regularly?”

“Oh, huh-uh. I’d been there maybe four or five times, and usually it was just to swing by to meet her on a day out with Ramona. That was bad luck the one night her mom came in. Vonda was always fawning all over Julia’s clothes the couple of times we’d hung out by the fountain together.”

“Here at the park, you mean?”

“Yeah. So then Julia told me the next time I saw Vonda, I should try bringing her around because Julia had all these clothes she wanted to give away. We were just about to leave when her mom came home. She acted like we were going to walk out with the china or something.”

“That was awfully generous of Julia. Was that typical?”

He shrugged. “Yeah, I guess. But she also wanted everyone to know when she did a good deed. Sorry, that sounds mean, under the circumstances.”

“Were you and Julia ever alone?”

The kid looked panicked. “You think I had something to do—”

“No, no,” Ellie said, taking a step backward to give him more space. “Nothing like that, Casey. I only asked to get a better sense of how well you knew Julia. It might help put your impressions in context.”

“Yeah, okay. Um, we never arranged anything with just the two of us or anything. But, yeah, a few times, we’d all be hanging out and Julia and I would end up walking in the same direction afterwards. One time, everyone else had to bail early, so we walked over to see the new part of the High Line when it first opened. You know, that kind of thing. Mostly, though, I’d say we knew each other through Ramona.”

“And I take it you know what happened to Julia last night?”

“That she died? Yeah, Ramona called me and I went up to her place. She said Julia’s mom doesn’t believe it’s suicide. Is that why you’re here?”

There was no reason for this kid to know that Ellie and her partner had a split of opinion on that issue. “You seem like a pretty straight shooter, Casey.”

He squinted. “I try to be.”

“So give it to me straight. What can you tell us about Julia that her best friend might not be willing to say?”

“There’s not a lot to tell. I mean, she’s super rich. Pretty. Probably had some baggage with her parents—always fighting with her mom, talking about her dad, trying to get more time with him, feeling kind of ignored. You know. But otherwise pretty normal.”

“Did she have a boyfriend?”

“No, it was more like she’d just hook up. She told me she was into some guy a few weeks ago, but I never asked what happened to that.”

“Who was the guy?”

“No clue. She only mentioned it once. Like I said, we were both friends with Ramona, but not as much with each other. This was during one of those few times we were actually alone. We’d gone to this place called Black and White.” Ellie suppressed a smile. The bar was a little lounge in the East Village where her brother, Jess, and his band, Dog Park, sometimes played open-mic nights on Sundays. She’d always teased Jess that the place was overrun by kids with fake IDs, but Jess wanted to believe it was the next CBGB. “Ramona hopped in a cab uptown, and I walked Julia home. She was pretty tipsy and was saying she was tempted to drunk-dial the guy. I was having a little fun with her, trying to get her to call him. Then she said she didn’t even have his cell phone number—that she wasn’t supposed to call or something. It was a little weird.”

“Does Ramona know?”

“I’m not sure. Julia said Ramona wouldn’t approve.”

“Why wouldn’t Ramona approve?”

“You know that daddy baggage I mentioned? Let’s just say it manifested itself in Julia’s dating preferences. Ramona was always trying to get her to see a therapist about it. I just assumed when she made that comment about Ramona not approving that it was some old guy.”

“How old are we talking about here?”

“Not, like, you know, Hugh Hefner old. But I think one guy last summer was, like, thirty! Ramona kind of lectured her about it, and since then I got the impression Julia decided the less Ramona knew about those things, the better.”

In any other situation, Ellie would bristle at the thought of thirty being “old.” But to have a relationship with a junior in high school? Thirty was ancient.

“What made you think she was keeping Ramona out of the loop?”

“Ramona seemed to buy Julia’s act that she wanted more down time to read and study and stuff. Maybe I’m too suspicious but it seemed to me she was lying. One time she said she’d gone to the rooftop at the Standard with this guy, Marcus, but then later Ramona found out Marcus was at a birthday party for some girl at school the same night. Ramona blew it off, but other times Julia would tell Ramona she fell asleep watching TV, and I could just tell she was lying. When she didn’t show up today, I assumed it was another one of her secret disappearances. I feel awful now.”

“How about her friends? Would you say she was well liked?”

“Seemed like it. They’re both a little more on the wild side, compared to all the matching mean girls at their school, but I think Ramona actually got hassled more than Julia for it. Julia’s dad kind of gave her the cred to be a little off. Compared to the kids at that school, Ramona’s family’s, like, poor or something.”

“And how exactly was Julia off, or I think you said a little wild? A lot of drinking? Drugs?”

“No, nothing more than the usual drinking. Maybe a little weed. It’s hard to explain. Just, you know, more curious about the rest of the world than rich kids usually are.”

“That’s funny. Growing up in Kansas, I always thought wealthy kids in New York were incredibly worldly.”

“I don’t mean living in Paris on your summer vacation. I mean hanging out downtown. Taking the subway.” He lowered his voice. “Being friends with people of a different status. Trying not to be the spoiled brats they’ve been bred to be.”

“And where do you fall on this status spectrum?” Ellie made sure not to look at the light stains near Casey’s shirt collar or the spot on the sleeve where the fabric was wearing thin.

“Pretty damn low.” He looked down at his canvas sneakers. “I’m currently residing—if you can call it that—at Promises. It’s what they call transitional housing for at-risk young adults. It’s what everyone else in the world calls a homeless shelter.”

“Is that where the other kids who went to Julia’s townhouse with you live, too? Brandon and Vonda?”

“Brandon does, but not Vonda. I haven’t seen her in, like, a week.”

“Do you have last names for them?”

According to Casey, Brandon was Brandon Sykes, sixteen years old. Casey had seen him just that day, and he was probably heading back to the shelter that night. Vonda was supposedly nineteen, but he suspected she was younger. He did not know her last name, nor did he know how to contact her.

“And the shelter’s the best address for you?” she asked.

“Until I win the lottery, that’s where I’m at. I guess you need stuff like ages and last names and addresses for police reports.”

She rotated her wrists in front of her. “Like I said, I do an awful lot of typing in this job. And this transitional housing for at-risk young adults is really a better place for you than with your family?” Ellie was no social worker, but she didn’t feel right about leaving this kid in a shelter without at least inquiring.

“My family’s in Iowa, and let’s just say they’re not real interested in being my family these days.”