По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

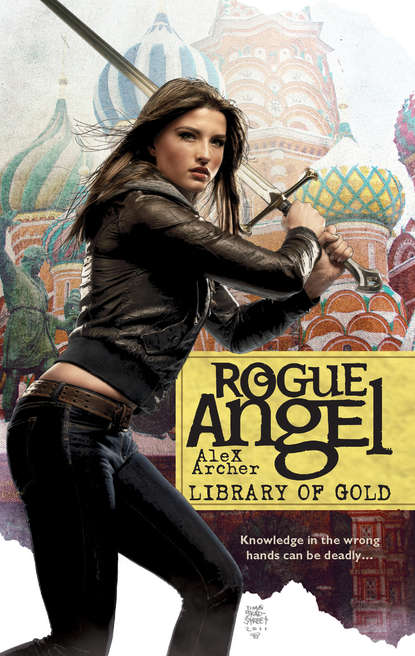

Library Of Gold

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“A mutual friend of ours in Paris said you might be able to help with a particular problem I’d like to solve.”

Annja only had one friend in Paris who could possibly run in the same social circles as Davies and that was Roux. Incredibly wealthy in his own right, perhaps even more wealthy than Charles Davies, Roux was unlike any other man she’d ever met. Save one.

He’d lived for more than five hundred years, which probably had something to do with that, she thought.

Roux had been an instrumental force in her life for years now. She had been with him when she’d discovered the final missing piece to the shattered sword that had once been wielded by Joan of Arc. Annja had been in Roux’s study with him when the blade had mystically reforged itself right before their very eyes and, by Annja’s way of thinking, had chosen her to be its next bearer. Since then Roux had become a kind of mentor to her, sharing what he knew of the blade and its purpose.

Which made sense given that the blade had had a significant impact on his life, as well.

He’d been Joan’s protector, charged with delivering her safely back behind French lines, a job he’d ultimately failed to do. Joan had been captured and, vastly outnumbered, he and his young apprentice, Garin Braden, had been unable to do anything but stand and watch as the English soldiers burned her at the stake for witchcraft and heresy. Joan’s sword had been shattered by the commander in charge of the execution detail, the pieces quickly gathered up by onlookers as souvenirs. It was only later that Roux discovered how his failure to live up to his vow to protect the young maiden had changed him and, by extension, his apprentice, as well. The two men stopped aging, appearing today just as they did five centuries before. Determined to be the master of his own fate, Roux had set out on a quest to reunite the shattered pieces of Joan’s sword, thinking that restoring the weapon might somehow end the curse.

Unfortunately, this brought him into rivalry with his former apprentice, Garin, who decided that he was quite happy living forever and didn’t see it as a curse at all. Because he saw the restoration of the blade as an attempt to undo the very act that had granted them an ageless life in the first place, Garin spent the next couple hundred years trying to kill Roux whenever he got the chance. It was only recently, when the blade had been reformed without any harm coming to them, that the two men had put aside their conflict and begun to cooperate.

Roux had sent customers her way on several occasions and so Annja wasn’t exactly surprised to hear of his recommendation.

“And how is the stubborn old goat?” she asked.

“As willful as ever,” Davis replied, “and determined to make everyone around him well aware of it.”

Their meal came, sea bass for Charles and a sirloin for Annja, and they spent the next thirty minutes enjoying the food and talking about inconsequential things. Once the table had been cleared and coffee ordered, Charles finally got down to business.

“What can you tell me about the Library of Gold?” he asked.

Annja didn’t even need to think about it. The library was one of the great unsolved mysteries of the archaeological world and she was well-versed in its history.

“It’s a collection of ancient books gathered over several hundred years by the Byzantine Empire and collected in the library at Constantinople. It supposedly included roughly eight hundred books written in Greek, Latin, Hebrew and Arabic, including some exceedingly rare volumes as a complete set of the “History of Rome” by Titus Livius, poems by Kalvos, “The Twelve Caesars” by Suetonius and individual works by Virgil, Aristophanes, Polybius, Pindar, Tacitus and Cicero.”

Annja took a sip of her wine, warming to the subject. “Many of the books would have been written by hand, which, if they surfaced on today’s market, would make them incredibly valuable. Never mind the several hundred editions that were supposedly created specifically for the various emperors, which were rumored to have had their covers inlaid with gold and encrusted with jewels of all shapes and sizes.

“When the emperor’s niece, Sophia Palaeologus, married the Grand Prince of Moscow, Ivan III, she took the library with her back to Russia. Reasons for this vary. Some say it was a part of her marriage dowry, while others insist that it was to keep the library from falling into the hands of Sultan Mahomet II, who was threatening Constantinople at the time. Either way it turned out to be fortuitous, because the sultan’s forces eventually sacked Constantinople. I guess in the end it really doesn’t matter. The library went to Russia and that pretty much sealed its doom.”

Charles was watching her closely, sizing her up it seemed. “Why’s that?” he asked.

“The difference in the cities themselves, for one. At the time, most of the buildings in Moscow were made of wood. Fires were frequent, the dry air leeching the moisture out of the wood in the summertime and causing them to burn fast. A small one-building fire could engulf an entire section of the city if it wasn’t quickly contained. Compare that with Constantinople, which was far older than Moscow and where most of the buildings were of cut stone. For this reason alone, the library was safer in Constantinople.

“Sophia apparently came to the same conclusion. Soon after arriving in Moscow, she convinced her new husband to rebuild the entire Kremlin, replacing the wooden structures with buildings of brick and stone. The library was moved to the Temple of the Nativity of the Theotokos and that’s where it remained until Sophia’s stepson, Ivan IV, came to power in 1533.”

“That hardly sounds like doom and gloom,” Charles said skeptically.

Annja smiled. “The library passed into the hands of Ivan IV, also known as Ivan the Terrible and the Butcher of Novgorod. This is the same man who killed his own son and heir in a fit of rage by striking him repeatedly over the head with an iron rod. He created a secret police force that was actively encouraged to rape, loot, torture and kill in his name to keep the populace under control. Does that sound like the kind of man priceless texts should be entrusted to?”

Charles grimaced and shook his head.

Annja went on. “Recognizing the potential danger the library was in, the Vatican tried to purchase it outright from the self-declared czar. Ivan refused. Afraid his enemies would try to take it from him by force, Ivan hired an Italian architect named Ridolfo di Fioravanti to design and build a secret vault to house the library. Months into the project Fioravanti and the library both vanished.”

“So what do you think happened to it?” Charles asked casually.

Annja thought about that one for a moment, then shrugged. “I don’t have a clue,” she said. “And given what’s gone on over there for the past century or so, we’ll probably never know.”

Charles leaned toward her, his eyes shining with excitement. “What would you say if I told you I knew where it was? Or, at least, had direct information that could lead you to it?”

Annja laughed. “If I had a nickel for every time someone told me they knew where to find a long-lost treasure, I’d be as rich as you are, Charles.”

He stared at her and then lifted his hand. The woman Annja had noticed earlier immediately got up and walked over. She nodded once at Annja, then slid a manila envelope into her boss’s hands before returning to her seat.

Charles put the envelope down on the table in front of him and folded his hands over it.

Annja couldn’t take her eyes off it. Her heart was racing with the same electric excitement she felt just before entering a lost tomb. When at last she tore her gaze away, she found Charles watching her with a wry grin.

“Last month I was approached by a young man named Gianni Travino, who claimed to be a descendent of the architect hired to build Ivan’s secret vault. After establishing that he was who he claimed to be, and that his family was, indeed, distantly related to Fioravanti himself, Gianni and I had a long chat.”

Charles paused and glanced around, and Annja realized it was all part of the show. Her host apparently loved a good story and he was milking this one for all it was worth.

That was fine with Annja. She was as much a romantic when it came to a mystery as anyone else. Perhaps even more so, given what she did for a living. She settled back and let Charles tell it his way.

“Gianni’s father passed away a few months ago and while going through the old man’s things, Gianni discovered a hand-carved wooden box that no one in the family remembered having seen before. None of his father’s keys fit the lock, so Gianni took it to a locksmith and had it opened. Inside he found a leather journal he claims was not only written by Fioravanti himself, but that also holds the key to finding the secret resting place of the Library of Gold.”

Annja could guess where this was going, as she’d heard stories like it a hundred times before. Charles was going to ask her to use the journal to track down the treasure and would offer some percentage of whatever they recovered in payment for her time and energy. She almost stopped him right then and there. But he’d invited her out for an expensive night on the town, something that didn’t happen all that often, and treated her with respect. A little courtesy wouldn’t cost her anything but a bit of time, and she had enough of that to go around at the moment.

Charles Davies surprised her. “As you can imagine, I was immediately skeptical,” he said. “I mean, come on, Fioravanti’s journal suddenly shows up after being hidden away in a wooden box in some old guy’s closet for the past four hundred years? Seriously?”

Annja laughed. Charles was well into his sixties and hearing him use language more suitable for someone a quarter his age struck her as highly amusing. Never mind the fact that he was calling someone else an “old guy.”

“I see you understand my skepticism,” he said with a twinkle in his eye. “That’s why I asked Mr. Travino to allow me to examine the journal and make a determination as to its authenticity on my own. Surprisingly, he was happy to let me.”

“And?”

Rather than answer her, Charles simply pushed the envelope in her direction.

Inside was a report from the office of David Carmichael, the chief archivist at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Annja had never met Carmichael, but she was familiar with his work and knew that you weren’t put in charge of the country’s historical records if you were sloppy with your science.

She turned the report to catch more light and began reading. It didn’t take her long to get the impact of what the document was saying.

Charles had sent the journal to Carmichael with the request that he do what he could to verify the historical provenance of the document. He’d supplied written permission from Gianni to run whatever tests were necessary, paid the required fees to cover the costs and included a generous contribution to the Smithsonian’s general fund in exchange for moving the project to the front of the line.

It had still taken two months, but that was far better than the three-year wait Annja knew it could have been.

The results were far from expected.

Glancing through the report and the accompanying documentation relative to the tests themselves, it was clear Carmichael had put the journal through the ringer. He’d tested the composition of the paper, ink, glue and leather cover, verifying that they were all produced somewhere between 1500 and 1550, which was smack in the middle of the time frame necessary for it to be authentic. Annja knew this wasn’t proof of the journal’s authenticity in and of itself. A good forger will use age-appropriate materials when assembling a forgery intended to pass close scrutiny, but at least it was a start.

As expected, Carmichael put the journal through other rounds of tests, such as examining the way the words were inscribed on the page as well as the language used within the text. He verified that the word usage and syllogisms were all appropriate to the time period in question.

His final conclusion?

While he couldn’t say for certain the journal had been written by Ridolfo di Fioravanti, Carmichael did confirm it had mostly likely been assembled in the mid-1500s in southern Italy and that the ink that was used to inscribe the text on its pages was of the type available in Russia during the same time period.

It was pretty solid support for Gianni and his story, as far-fetched as it might seem.